One of Nate B. Jones’ recent videos has the title Why the Smartest AI Bet Right Now Has Nothing to Do With AI (It’s Not What You Think). While the title is technically correct, I think it should be changed to In the Age of AI, You Have to Beat the Bottlenecks.

Bottleneck: a definition

Many Global Nerdy readers aren’t native English speakers, so here’s a definition of “bottleneck”:

A bottleneck is a specific point where a process slows down or stops because there is too much work and not enough capacity to handle it. It is the one thing that limits the speed of everything else.

Imagine a literal bottle of water.

The body of the bottle is wide and holds a lot of water.

The neck (the top part) is very narrow.

When you try to pour the water out quickly, it cannot all come out at once. It has to wait to pass through the narrow neck.

In business or technology, the “bottleneck” is that narrow neck. No matter how fast you work elsewhere, everything must wait for this one slow part.

Elon is often wrong, but you can learn from his wrongness

My personal rule is that when Elon Musk says something, and especially when it’s about AI, turn it at least 90 degrees. At the most recent World Economic Forum gathering in Davos, he talked a great “abundance” game, with sci-fi claims that AI would create unlimited economic expansion and plenitude for all:

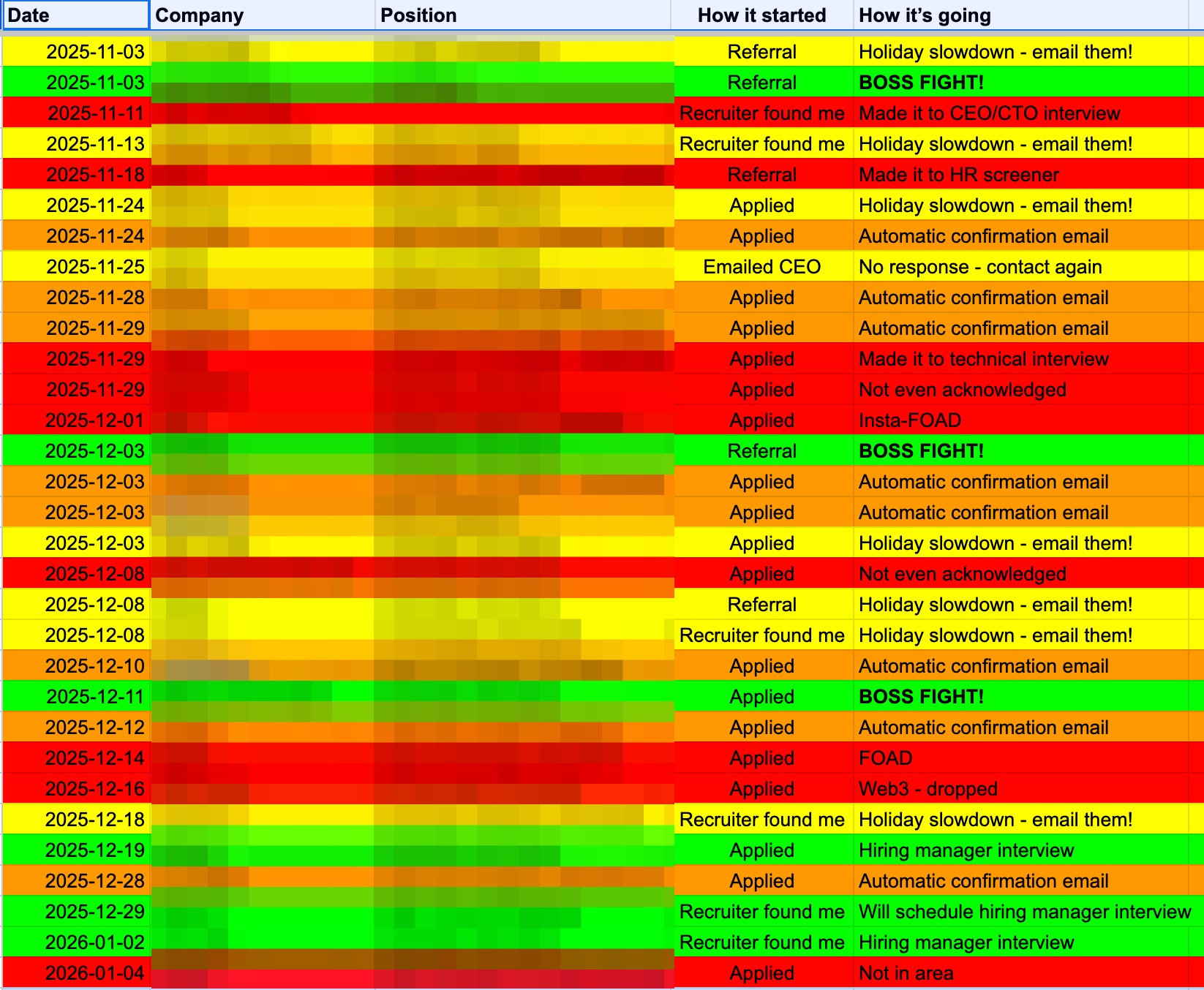

Nate Jones watched the talk with Musk, but came to the conclusion that Musk’s take is the wrong frame for the immediate future. The current AI era will be one of bottlenecks, not abundance. I agree, as I’ve come to that conclusion about any grandiose statement that Musk makes; after all, he is Mr. “we’ll have colonies on Mars real soon now.”

Here are my notes from Jones’ video…

Notes

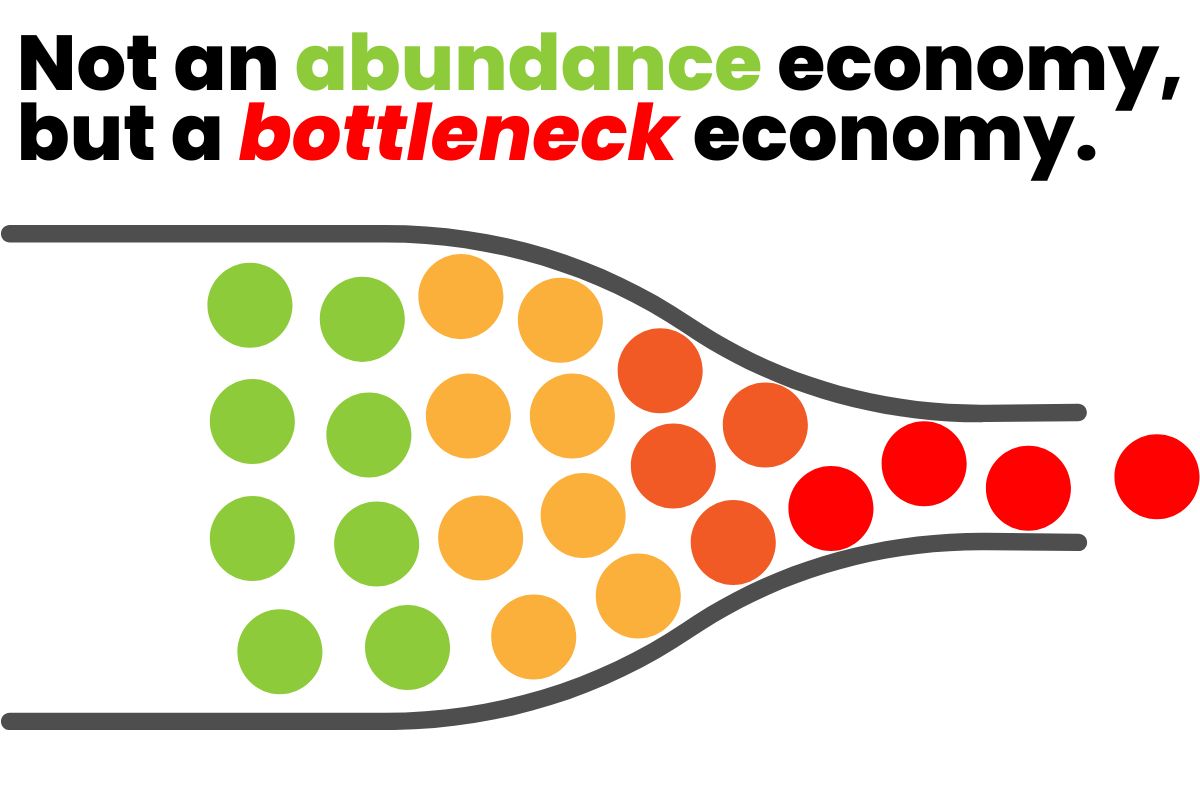

Instead of abundance, Nate suggests that what we are entering is a “bottleneck economy.” While AI capability is growing, the actual value it produces won’t automatically flow everywhere and benefit everyone. Instead, it will concentrate around specific areas based on AI’s constraints and limitations [00:00].

Research from Cognizant claims AI could unlock $4.5 trillion in U.S. labor productivity (and yes, you need to take that figure with a huge grain of salt), and it comes with a massive caveat: businesses must implement AI effectively. Currently, there’s a wide gap between AI models and the hard work of integrating them into business workflows. This “value gap” means that the trillion-dollar impact won’t materialize until organizations figure out how to bridge the distance between models can do in general and what they can specifically do for a company’s operations [01:01].

Physical infrastructure is the first bottleneck. AI capability is increasingly constrained by things it needs from the physical world, specifically land, power, and skilled trade workers. Building the data centers required to train and run models takes years, and not just for the building process, but also permitting and connections to the power grid. This creates a wedge between the speed of software development and building infrastructure [03:56].

Beyond just buildings and power, the hardware supply chain is the second bottleneck. Access to compute, high-bandwidth memory, and advanced chip manufacturing (controlled largely by TSMC) determines who gets a seat at the table. Companies that understand this are securing resources years in advance and treating regions with stable power and friendly permitting as strategic assets. This creates a market where value is captured by those navigating physical constraints in addition to building better algorithms [06:02].

The third bottleneck is one you might not have thought of: the cost of trust. As the cost of generating content collapses to near zero, the cost of trust is skyrocketing. Jone highlights what he calls a “trust deficit,” calling it a major coordination bottleneck. When any content can be fabricated, the ability to verify and authenticate information becomes expensive and crucial. Value will shift to institutions, platforms, or individuals who can mediate trust and provide a reliable signal in world rapidly filling with synthetic media slop [07:36].

For organizations, there’s the bottleneck of applying general AI to specific contexts. A general AI model won’t know a company’s private code base, board politics, or competitive dynamics. The bridge between “AI can do this” and “AI does this usefully here” requires tacit knowledge; that is, the practices and relationships that aren’t written down but live in the heads of the company’s employees. Companies that solve this integration problem will unlock productivity, while those that don’t will spend lots of money on tools they never use [09:55].

The fifth bottleneck is another one you might not have though of: the increasing value of taste. For individuals, and especially for those in tech, the bottlenecks are shifting from acquiring skill to getting good at making judgment calls. AI is commoditizing hard skills like programming (it’s cutting down the time to proficiency from years to months), the really valuable skills are going to be taste and curation. The ability to distinguish between AI output that’s “good enough” versus AI output that’s extraordinary will become the differentiator. Developing taste takes experience, time, and observation. This is going to create a dangerous race for early-career professionals, whose entry-level work is being devalued [14:52].

The combination of problem-finding and execution are the sixth bottleneck. When problem-solving becomes automated, finding the problem and executing on the solution become the new moats. The market will reward those who can frame the right questions and navigate the ambiguity of implementing appropriate solutions. Jones emphasizes that while AI can generate a strategy or a plan, it can’t execute the “grinding work” of follow-through, holding people accountable, and navigating organizational politics. Success depends on identifying these new personal bottlenecks rather than optimizing for old skills that AI is turning into commodities [16:50].

Tips for techies and developers to beat the bottlenecks

- Cultivate a sense for taste in addition to a skill for syntax. As coding moves from purely “grind” to at least partially “vibe” (see my vibe code vs. grind code post), your value shifts from writing code to reviewing AI-generated code. You need to refine your sense of what makes code good to differentiate yourself from the flood of AI output, which tends towards the average. [15:06]

- Specialize! To beat the “good enough” standard of AI, pick a niche, and specialize in it. The window for being a generalist is closing, and extraordinary depth allows you to spot quality that AI (which once again, tends towards the average) misses. [16:16]

- Pivot to problem finding. AI makes a lot of problem solving cheap, which makes problem finding the rare and precious thing. Stop defining yourself solely as a problem solver. Focus on defining the right problems to solve, framing the architecture, and determining direction. This management-level skill is harder for AI to replicate than execution. [16:50]

- Value tacit knowledge and context. Tacit knowledge is the “soft” knowledge of how an organization works, and it’s almost never documented (at least directly), but lives in the heads of the people working there. Knowing why a legacy codebase exists or understanding specific stakeholder needs is a “context moat” that general AI models can’t easily infer. [17:36]

- Focus on execution and follow-through. AI can generate the plan/code, but it can’t navigate the friction of deployment. The “grinding work” of implementation, such as convincing teams, fixing integration bugs, and finalizing products, is where the real value now lies. [18:47]

- Build your tolerance for ambiguity. This has always been good for real life, but now it’s also good for tech work, which used to live in rigid, well-defined, unambiguous spaces… but not anymore! The tech landscape is shifting rapidly, and the ability to remain functional and productive while “metabolizing change” and dealing with uncertainty is a critical soft skill that separates leaders from people who freeze when things become ambiguous. [20:01]

- Audit your personal bottlenecks: Be honest about what is actually constraining your career right now. It might not be learning a new framework (the old bottleneck). Instead, it might be your ability to integrate AI tools into your workflow or your ability to communicate complex ideas. Find those bottlenecks and come up with strategies to overcome them! [21:25]