I’ve often been asked “How do you keep up with what’s going on in the AI world?”

One of my answers is that I watch Nate B. Jones’ YouTube channel almost daily. He cranks them out at a rate that I envy, and they’re full of valuable information, interesting ideas, and perspectives I might not otherwise consider.

If you haven’t seen this channel before, he recently published a great “starter video” titled The People Getting Promoted All Have This One Thing in Common (AI Is Supercharging this Mindset). It covers a topic that should be interesting to a lot of you: What to do when the traditional career ladder is getting dismantled, and yes, the answer involves AI.

Here’s the video, and below it are my notes. Enjoy!

Notes

- Kiss the traditional career ladder goodbye

- High agency and locus of control

- High agency vs. systemic barriers

- AI as the “jet engine” for agency

- Speed becomes what sets you apart

- The “Say/Do Ratio” and execution

- Solo founders and lean unicorns

- Don’t wait; generate!

Kiss the traditional career ladder goodbye

The conventional path for white-collar career advancement that’s been around since the end of World War II is being dismantled. It used to be that you’d land an entry-level role, learn through work that starts as simple tasks but gets more complex as you go, and gradually climb the corporate ladder. That’s not the case anymore. If you’ve been working for five or more years, you’ve seen it; if you’re newer to the working world, you might have lived it.

Jones opens the video with these worrying stats:

- Entry-level hiring at major tech companies has dropped by over 50% since 2019

- Job postings across the US economy have declined by 29%

- The unemployment rate for recent college grads is now greater than the general unemployment rate

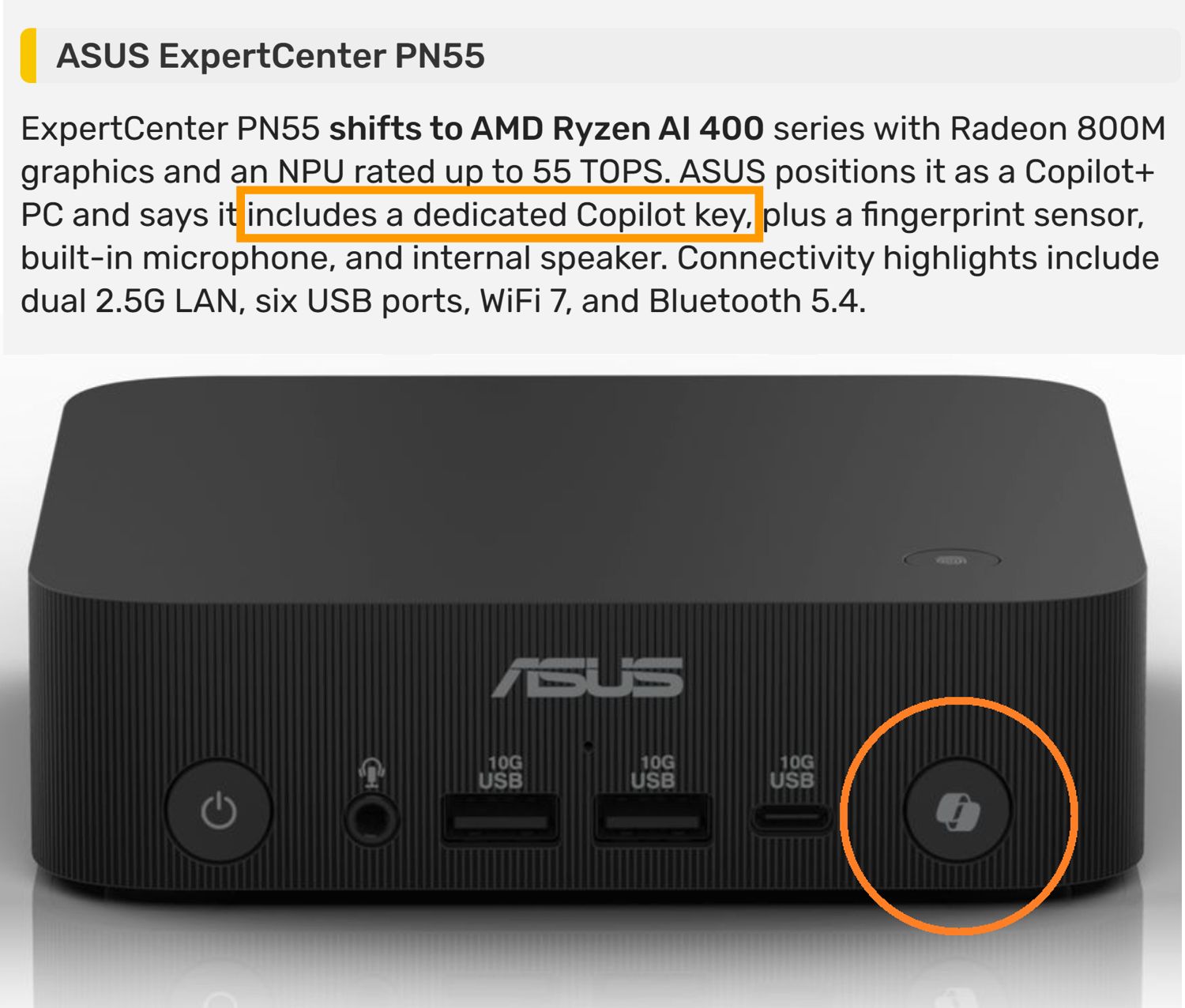

This isn’t a temporary freeze but a structural shift where the “training rung” of the ladder is being removed. Those repetitive, easier tasks that you assign to juniors (summarizing meetings, cleaning data, drafting low-stakes documents) are exactly what generative AI now handles, and it’s getting better at it all the time.

As a result, the “ladder” is being disassembled while people are still trying to stand on it. Entry-level roles now require experience that entry-level jobs no longer provide because AI has cannibalized the work that used to serve as the learning ground [00:55]. Jones argues that in a world where the passive route of “doing your time”to get promoted is vanishing, the only viable strategy left for career survival and growth is cultivating extreme high agency.

High agency and locus of control

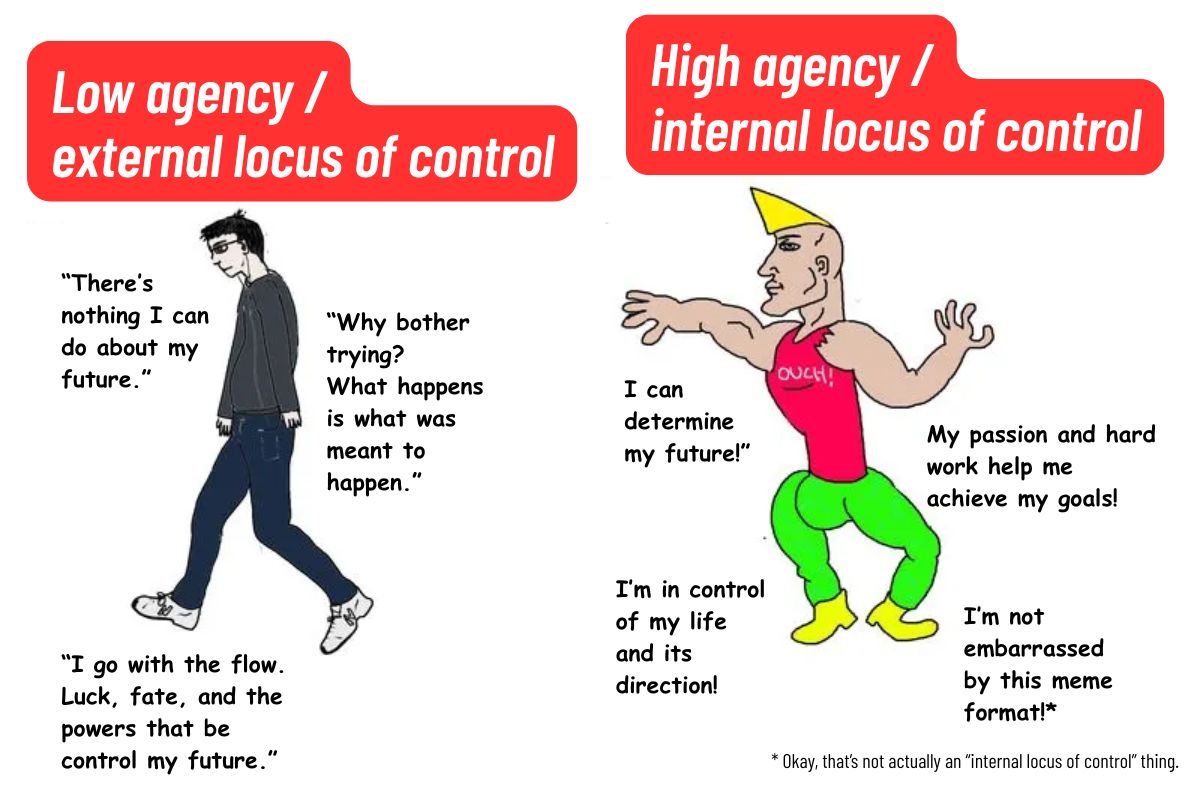

High agency sounds like a feeling of confidence, self-assuredness, or empowerment. It’s best understood through the theory of Locus of Control, which psychologist Julian Rotter developed in the 1950s.

Jones proposes a mental exercise [1:55]: draw a circle and list all major life elements (promotions, skills, family, economy). For low-agency individuals, significant factors like promotions or learning requirements fall outside the circle, perceived as things determined by managers or the market. For high-agency individuals, absolutely everything falls inside the circle.

The high agency mindset dictates that while you cannot control external events, you can control the way you respond, and by extension, your trajectory (sounds like the modern stoicism that’s popular in Silicon Valley circles, as well as at my former company Auth0).

When a high-agency person encounters a barrier that seems outside their control, they reframe it with a four-word Gen Z expression: “That’s a skill issue” [03:23]. Whether it’s lacking a technical skill or not knowing how to navigate office politics, they view the obstacle not as an immovable wall, but as a gap in their own abilities that can be bridged through learning and adaptation.

High agency vs. systemic barriers

Jones took the time to address the valid criticism that this mindset ignores systemic unfairness or is that “bootstrap mentality” that ignores structural problems. He argued that high agency is actually most critical for those with the least privilege. He observes that people from disadvantaged backgrounds often display higher agency because they lack the safety nets that more advantaged people have, which often leads them to be more passive [4:48]. When failure isn’t an option, you put in the effort not to fail.

While no one literally controls whether they get laid off, the high-agency mindset focuses on controlling the response: where to direct energy, what to learn next, and how to pivot.

However, Jones warns that an internal locus of control can be taken too far, leading to the tendency to blame yourself for everything that goes wrong. The goal isn’t to beat yourself up for every setback. Instead, it’s to channel that internal orientation into a “challenge” mindset. Instead of thinking “I failed because I’m inadequate,” the high-agency approach is “I haven’t found the right angle of attack yet, but I can figure it out” [5:41]. This distinction, which looks a lot like “growth mindset,” turns potential anxiety into a strategic focus on solving problems.

AI as the “jet engine” for agency

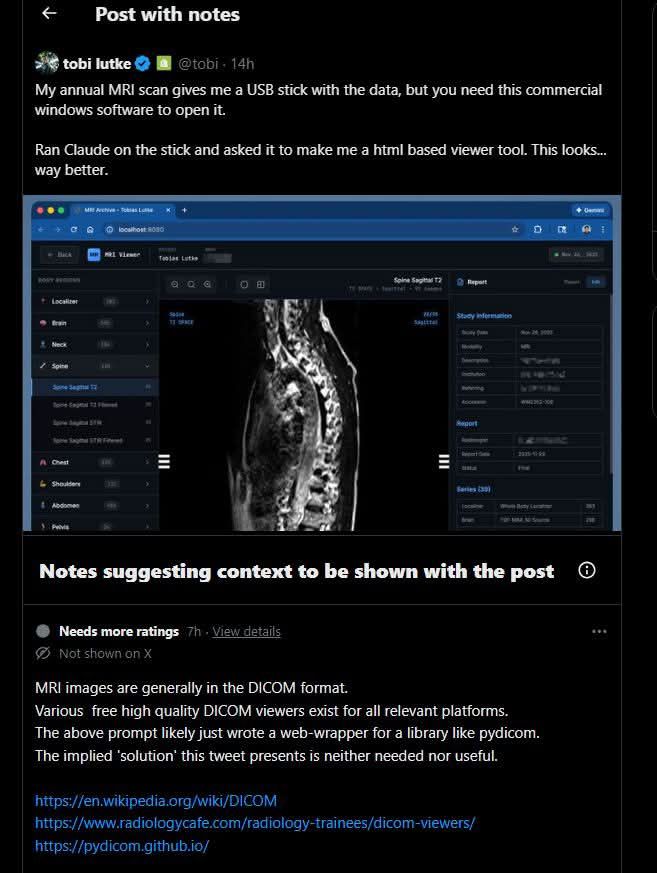

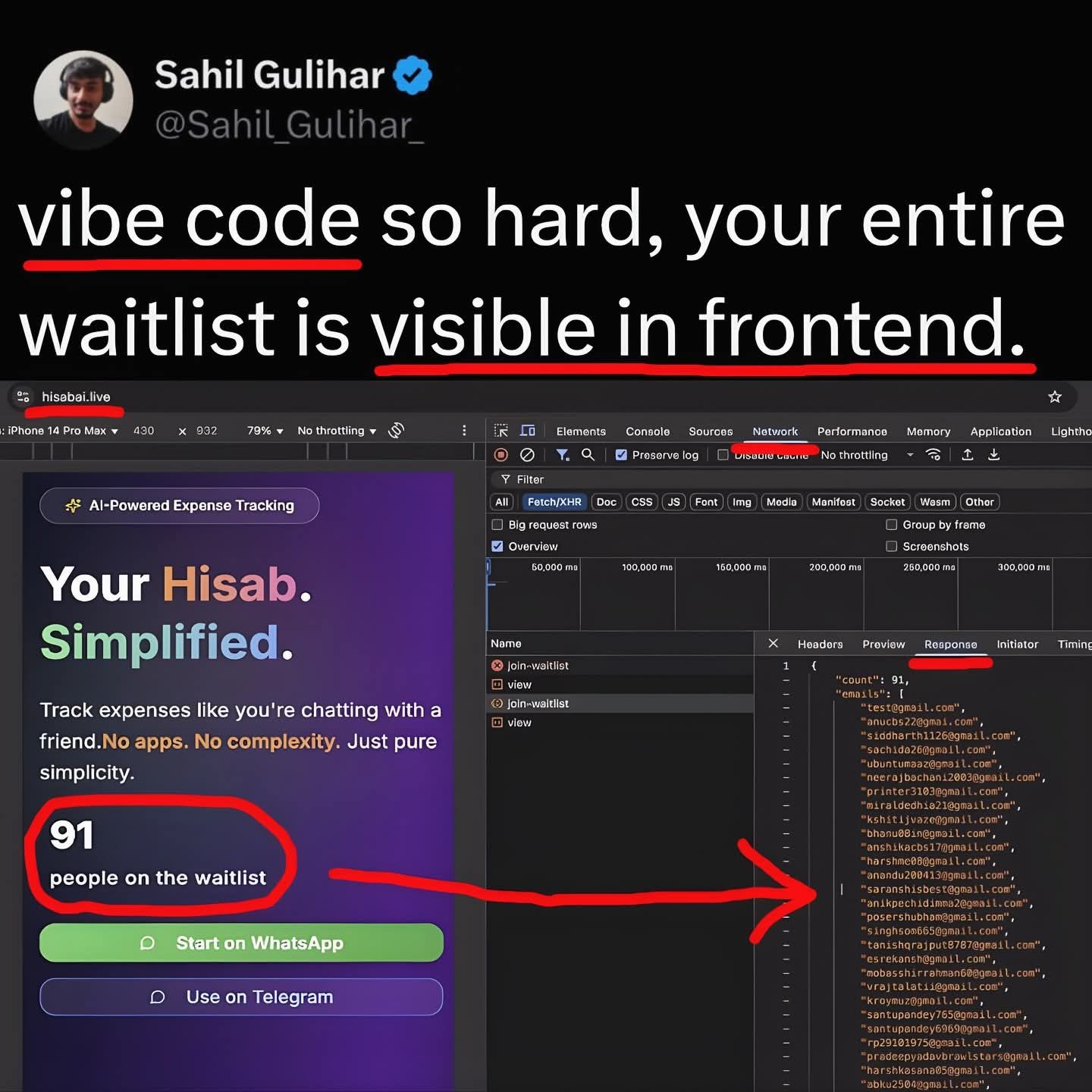

Jones’ thesis is that AI is the “greatest equalizer for agency that has ever existed” because it acts as a force multiplier for anyone willing to act [5:59]. Barriers that previously required years of expensive education or access to elite networks, such as coding a website, analyzing complex data, or launching a marketing campaign, can now be overcome by a single individual with a laptop and determination. AI doesn’t care about your pedigree; it simply responds to questions and executes commands.

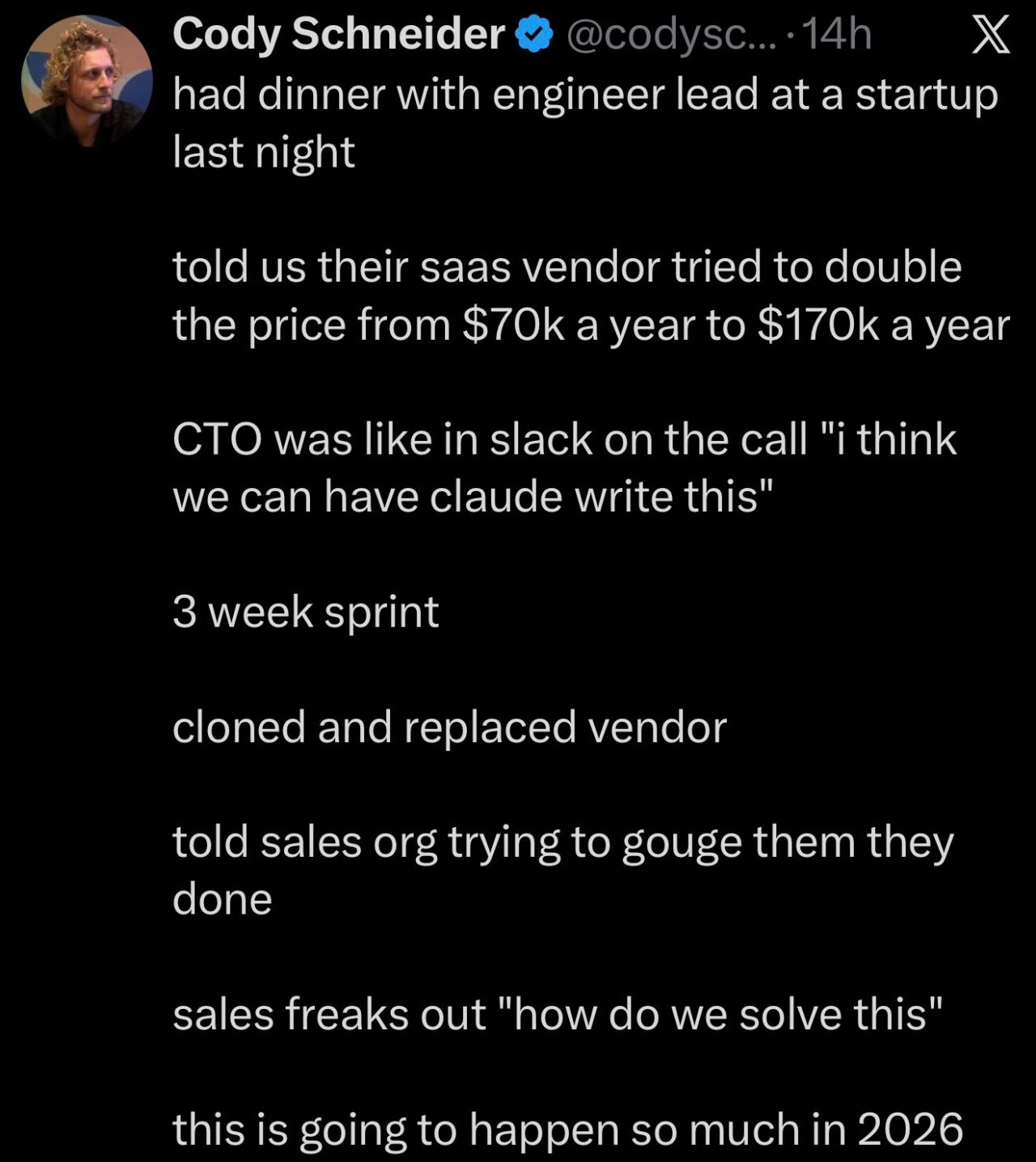

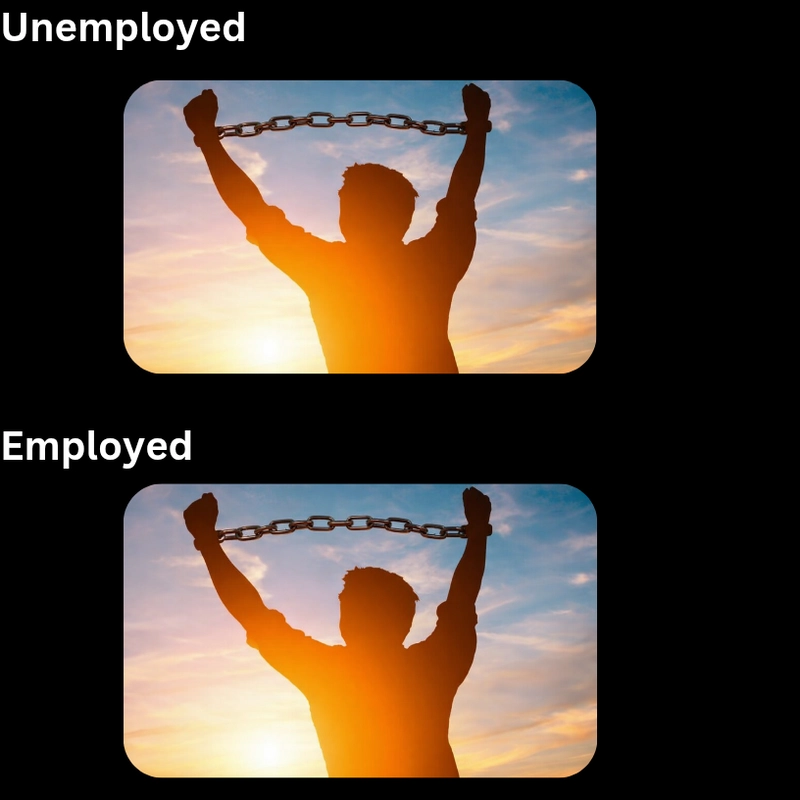

This technological shift allows high-agency individuals to bypass traditional gatekeepers. Jones shares examples of people (including the creator of Base44) moving from dead-end situations to running scaling businesses not because of luck, but because they used AI to relentlessly patch their skill gaps [6:12]. In this new era, if you don’t know a programming language or a business concept, AI allows you to learn and implement it simultaneously, effectively turning “skill issues” into temporary speed bumps rather than dead ends.

Speed becomes what sets you apart

A critical consequence of the AI era is the acceleration of the gap between high and low-agency individuals. Jones notes that while this difference used to play out over decades, AI now makes the separation visible in months [7:33]. High-agency people leveraging AI can accomplish 10 to 100 times more than their passive counterparts, compressing career trajectories that used to take twenty years into a fraction of the time (supposedly; consider the myth of the 10x developer). Conversely, career stagnation that once took a decade to notice (you sometimes see this in “company lifers”) now becomes apparent almost immediately.

This acceleration means that waiting for permission or the next rung of the ladder to appear is a strategy for failure. The people currently being tapped for leadership are those who combine high agency with “AI-native” thinking, leading them to redefine roles instead of just filling them [8:11]. In an organizational structure that is inherently malleable and constantly disrupted by scaling intelligence, titles don’t matter. Instead, what really matters is generating value and outcomes.

The “Say/Do Ratio” and execution

Jones talks about what he calls the “Say/Do Ratio” as a measure of high agency. It’s the gap between saying you will do something and actually doing it.

Most people have a poor ratio, letting weeks or months pass between intention (“I’m going to learn this skill!” or “I’m going to hit the gym daily!”) and action. They’re either hit by “analysis paralysis” or waiting for perfection [12:37]. High-agency individuals shrink the distance between “say” and “do.” They start immediately, even when they feel unprepared or uncomfortable.

AI serves as a powerful accelerator for improving this ratio by helping users “ship halfway-done” work (think “Minimum Viable Product”) or get past the “blank page” problem instantly.

Jones cites Kobe Bryant as a prime example of this mindset. Bryant viewed nervousness not as an emotion to be managed, but as an information signal that he hadn’t prepared enough, which is a variable that he could control [11:38]. Similarly, in the AI age, preparation and execution are more accessible than ever, allowing those with high agency to move from idea to prototype without getting stuck in the “planning” phase.

Solo founders and lean unicorns

The combination of high agency and AI is reshaping the business landscape, and the surge in solo founders and “lean” billion-dollar companies. Jones points out that the share of startups with solo founders has nearly doubled since 2015, and we’re approaching the era of the one-person billion-dollar company [15:13]. He cites the example of solo founder Maor Shlomo, who built Base44 from a side project to an $80 million exit in six months without a full-time team or venture capital, simply by pushing code to production 13 times a day [16:20].

This trend proves that AI allows individuals to operate with the output capacity of entire teams. Founders and operators can now “speedrun” through obstacles that used to require hiring specialists, whether it’s understanding server-side architecture or generating marketing materials. The constraint on building a massive business is no longer headcount or capital, but the agency of the founder to utilize AI to extend their own capabilities and solve problems [16:47].

Don’t wait; generate!

In the end, the high-agency mindset is grounded in an obsession with pushing value into the world. Jones describes this as a belief that the world is “bendable”: if you generate enough value and contribute enough, the world will eventually respond in your favor [18:15].

This orientation prioritizes contribution over extraction; instead of asking “What can I get?”, high-agency people ask “What can I create?”. Simply put, you get what you give.

This perspective shifts the focus from waiting for opportunities to making them. If you approach AI as a tool to expand your locus of control, you can systematically knock down barriers between you and your goals. Jones concludes that the future belongs to those who don’t wait for the old structures to return but instead use their agency to build, ship, and learn now, viewing the current disruption not as a threat, but as an unprecedented opportunity for growth [21:44].