Today’s my last day in my role as the developer advocate for HP’s GB10-powered AI workstation, the ZGX Nano. As I’ve written before, I’m grateful to have had the the opportunity to talk about this amazing little machine.

Of course, you could expect me to talk about how good the ZGX Nano is; after all, I’m paid to do so — at least until 5 p.m. Eastern today. But what if a notable AI expert also sang its praises?

That notable expert is Sebastian Raschka (pictured above), author of a book I’m working my way through right now: Build a Large Language Model (from Scratch), and it’s quite good. He’s also working on a follow-up book, Build a Reasoning Model (from Scratch).

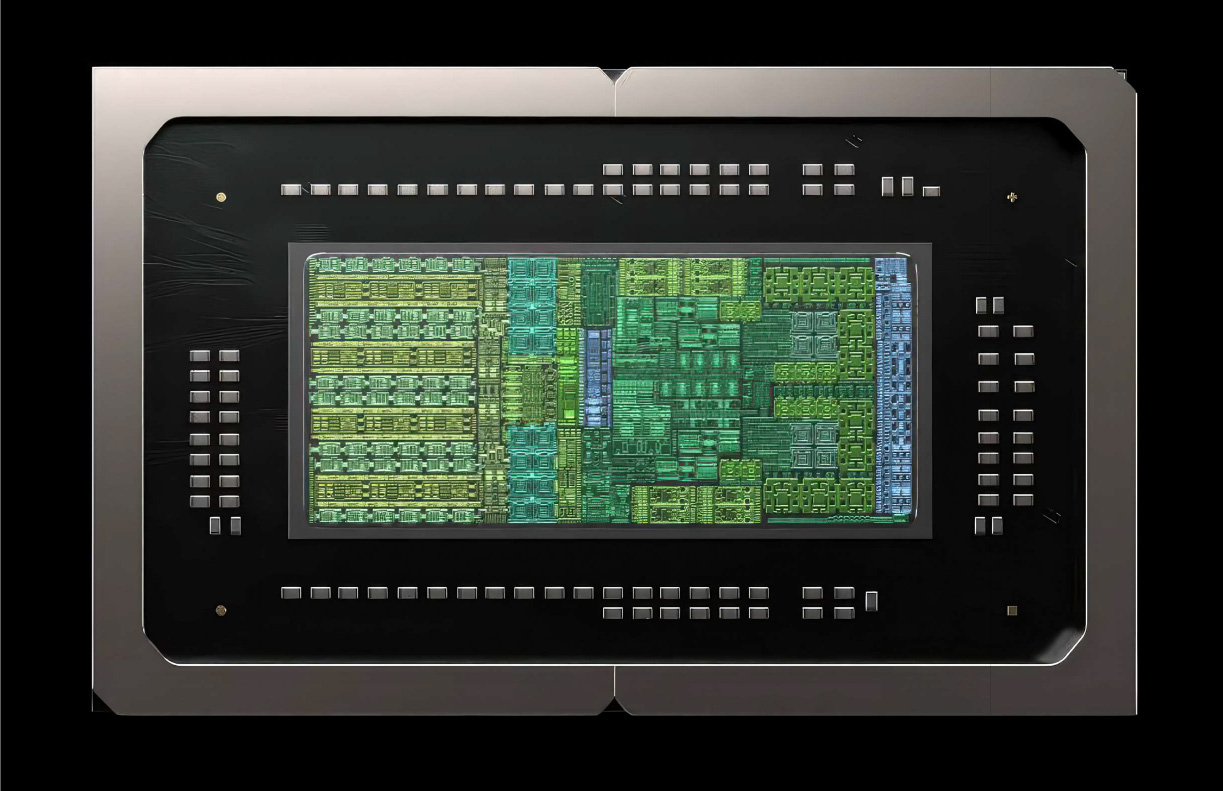

Sebastian has been experimenting on NVIDIA’s DGX Spark, which has the same specs as the ZGX Nano (as well as a few other similar small desktop computers built around the NVIDIA’s GB10 “superchip”), and he’s published his observations on his blog in a post titled DGX Spark and Mac Mini for Local PyTorch Development. He ran some benchmark AI programs comparing his Mac Mini M4 computer (a fine developer platform, by the bye) and the NVIDIA H100 GPU (and NVIDIA’s A100 GPU when an H100 wasn’t available), pictured below:

Keep in mind that the version of the H100 that comes with 80GB of VRAM sells for about $30,000, which is why most people don’t buy one, but instead rent time on it from server farms, typically at about $2/hour.

Let me begin from the end of Raschka’s article, where he writes his conclusions:

Overall, the DGX Spark seems to be a neat little workstation that can sit quietly next to a Mac Mini. It has a similarly small form factor, but with more GPU memory and of course (and importantly!) CUDA support.

I previously had a Lambda workstation with 4 GTX 1080Ti GPUs in 2018. I needed the machine for my research, but the noise and heat in my office was intolerable, which is why I had to eventually move the machine to a dedicated server room at UW-Madison. After that, I didn’t consider buying another GPU workstation but solely relied on cloud GPUs. (I would perhaps only consider it again if I moved into a house with a big basement and a walled-off spare room.) The DGX Spark, in contrast, is definitely quiet enough for office use. Even under full load it’s barely audible.

It also ships with software that makes remote use seamless and you can connect directly from a Mac without extra peripherals or SSH tunneling. That’s a huge plus for quick experiments throughout the day.

But, of course, it’s not a replacement for A100 or H100 GPUs when it comes to large-scale training.

I see it more as a development and prototyping system, which lets me offload experiments without overheating my Mac. I consider it as an in-between machine that I can use for smaller runs, and testing models in CUDA, before running them on cloud GPUs.

In short: If you don’t expect miracles or full A100/H100-level performance, the DGX Spark is a nice machine for local inference and small-scale fine-tuning at home.

You might as well replace “DGX Spark” in his article with “ZGX Nano” — the hardware specs are the same. The ZGX Nano shines with HP’s exclusive ZGX Toolkit, a Visual Studio Code extension that lets you configure, manage, and deploy to the ZGX Nano. This lets you use your favorite development machine and coding environment to write code, and then use the ZGX Nano as a companion device / on-premises server.

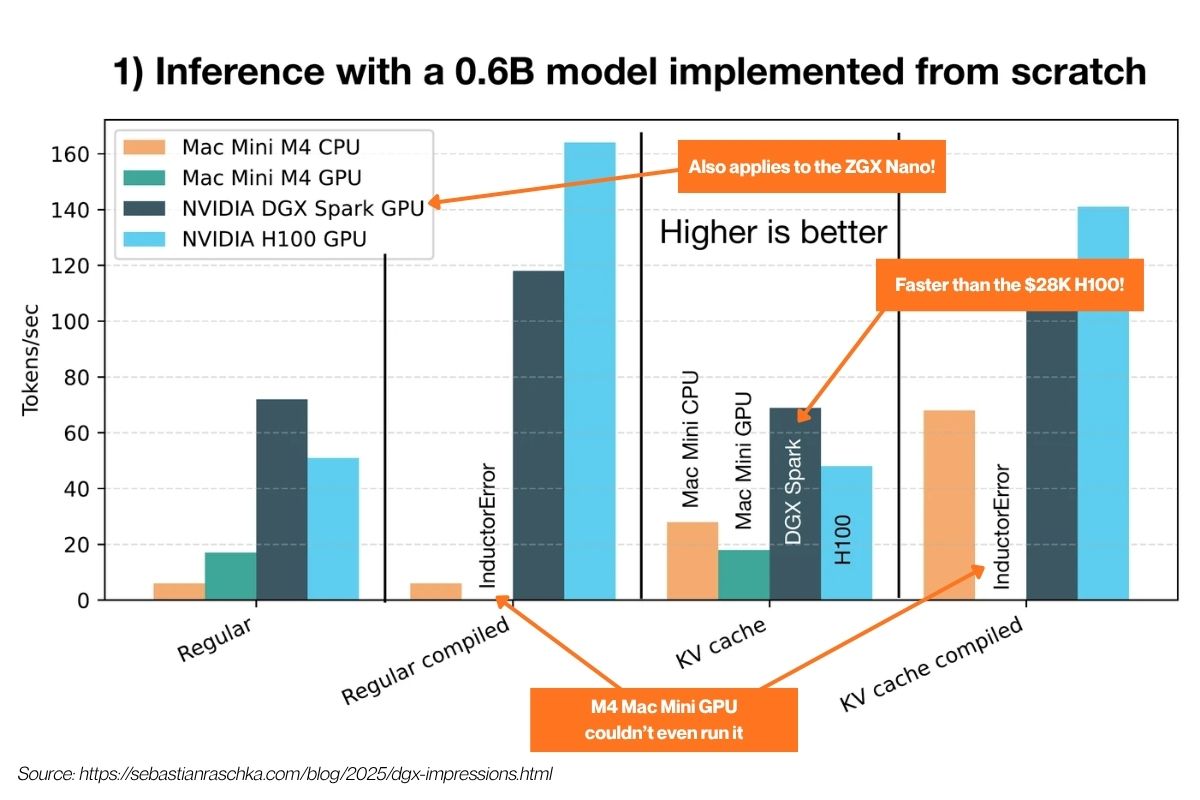

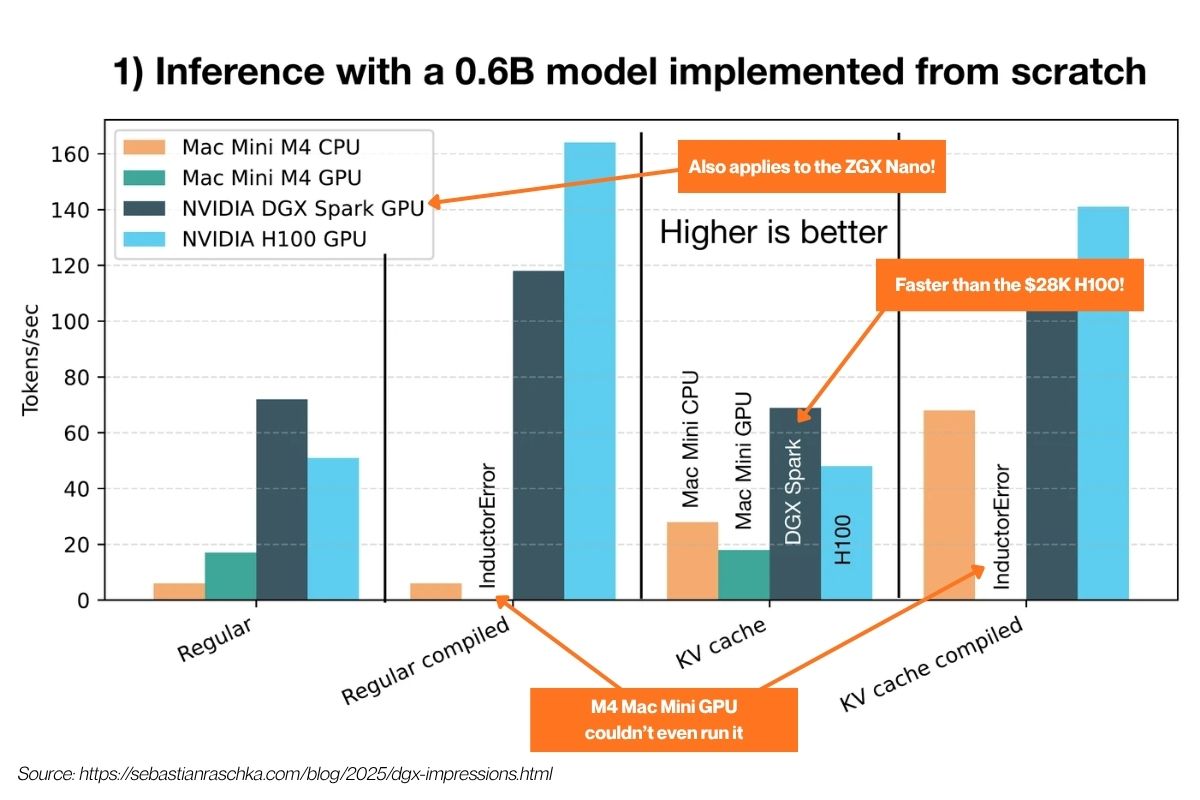

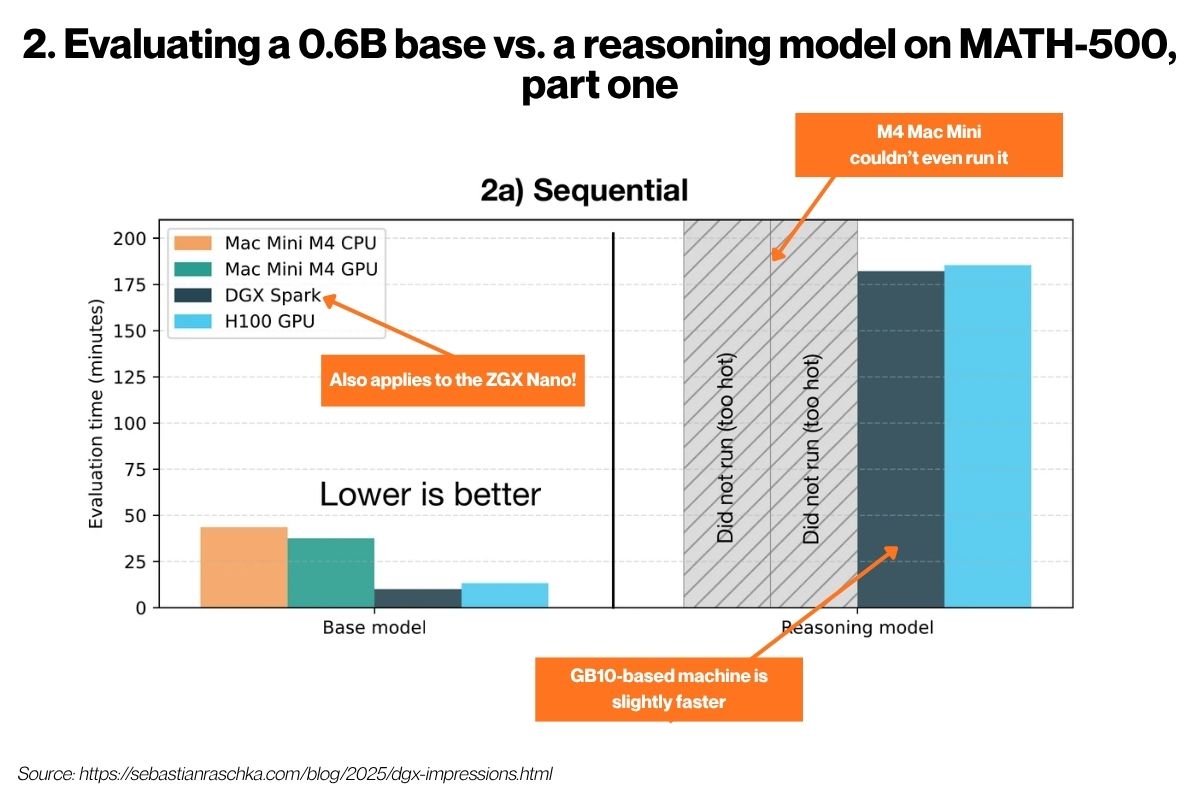

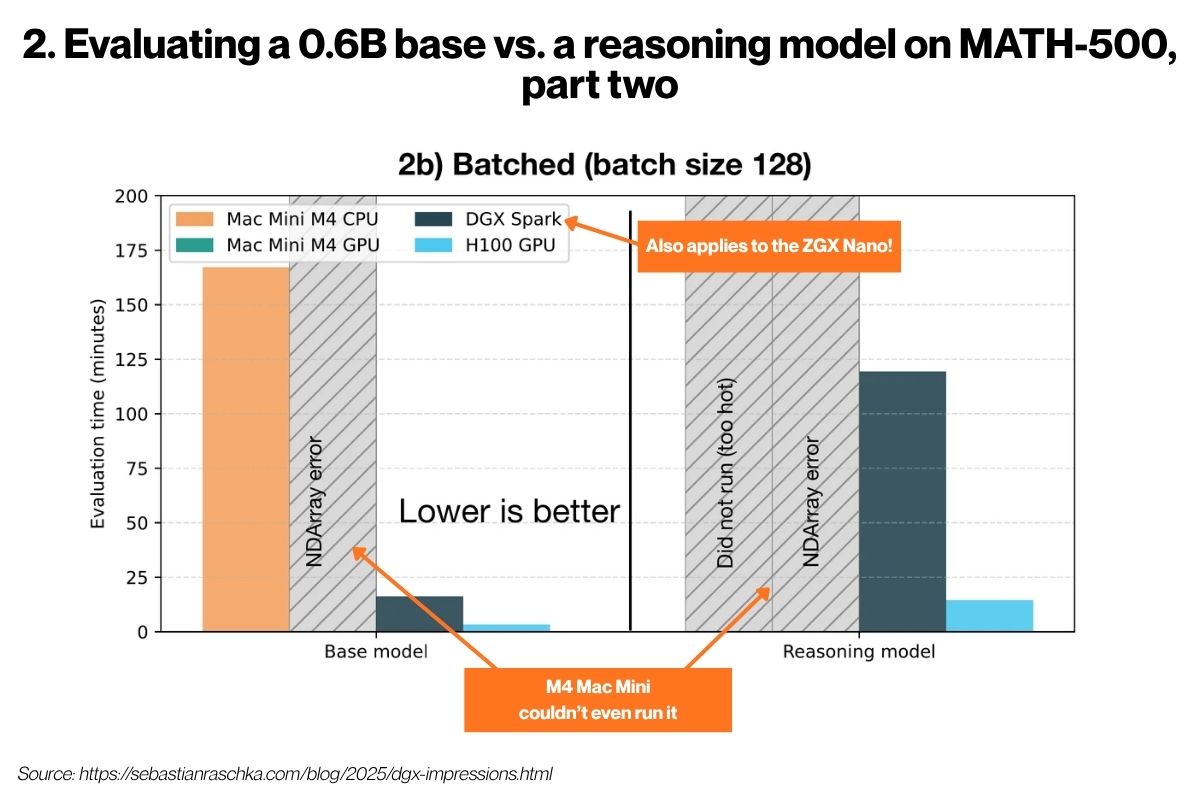

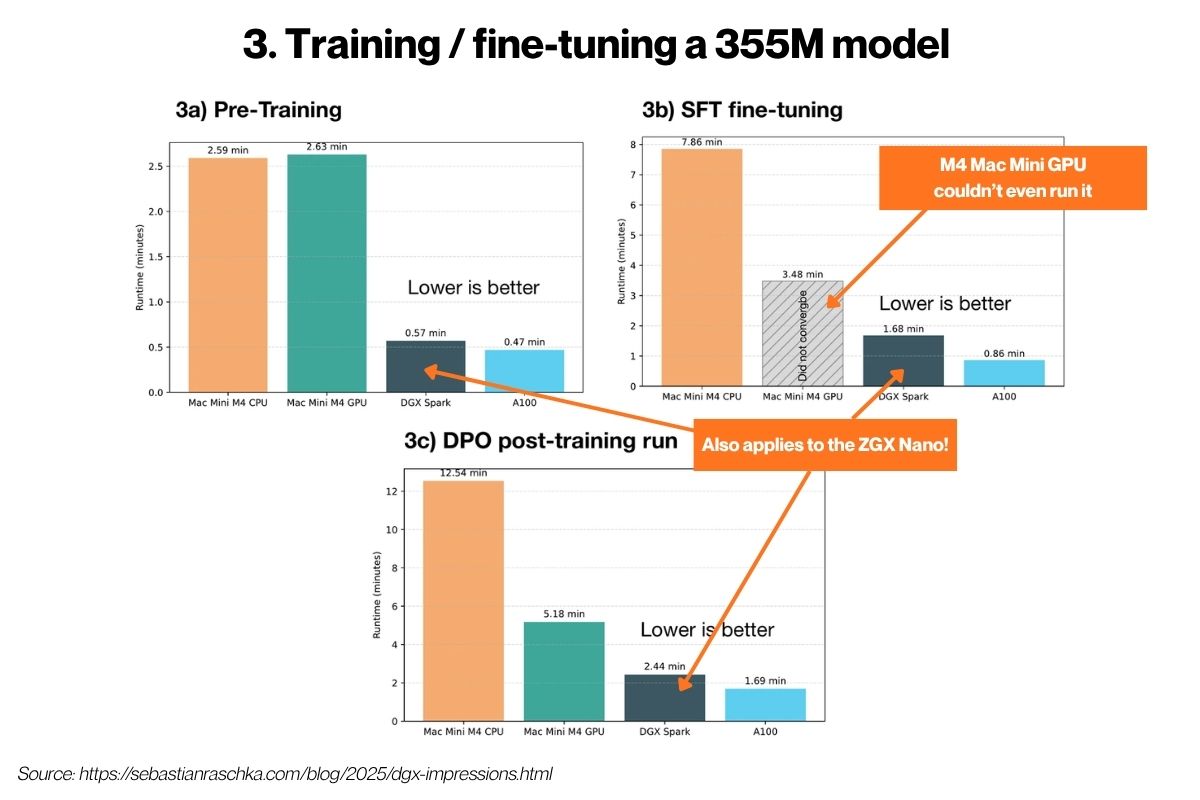

The article features graphs showing his benchmarking results…

In his first set of benchmarks, he took a home-built 600 million parameter LLM — the kind that you learn how to build in his book, Build a Large Language Model (from Scratch) — and ran it on his Mac Mini M4, the ZGX Nano’s twin cousin, and an H100 from a cloud provider. From his observations, you can conclude that:

In his first set of benchmarks, he took a home-built 600 million parameter LLM — the kind that you learn how to build in his book, Build a Large Language Model (from Scratch) — and ran it on his Mac Mini M4, the ZGX Nano’s twin cousin, and an H100 from a cloud provider. From his observations, you can conclude that:

- With smaller models, the ZGX Nano can match a Mac Mini M4. Both can crunch about 45 tokens per second with 20 billion parameter m0dels.

- The ZGX Nano has the advantage of coming with 128GB of VRAM, meaning that it can handle larger models than the MacMini could, as it’s limited by memory.

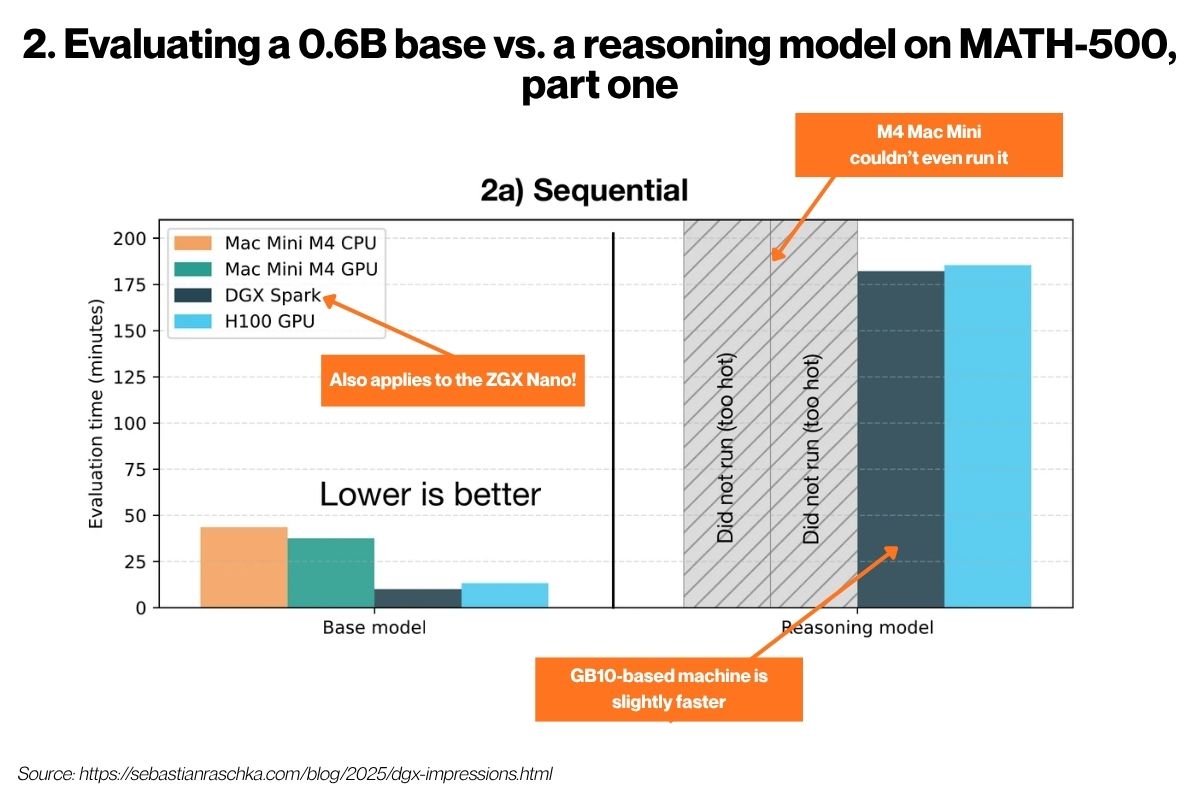

Raschka’s second set of benchmarks tested how the Mac Mini, the ZGX Nano’s twin cousin, and the H100 handle two variants of a model that have been presented with MATH-500, a collection of 500 mathematical word problems:

Raschka’s second set of benchmarks tested how the Mac Mini, the ZGX Nano’s twin cousin, and the H100 handle two variants of a model that have been presented with MATH-500, a collection of 500 mathematical word problems:

- The base variant, which was a standard LLM that gives short, direct answers

- The reasoning variant, which was a version of the base model that was modified to “think out loud” through problems step-by-step

He ran two versions of this benchmark. The first was the sequential test, where the model was presented on MATH-500 question at a time. From the results, you can expect the ZGX Nano to perform almost as well as the H100, but at a significantly smaller fraction of the cost! It also runs circles around the Mac Mini.

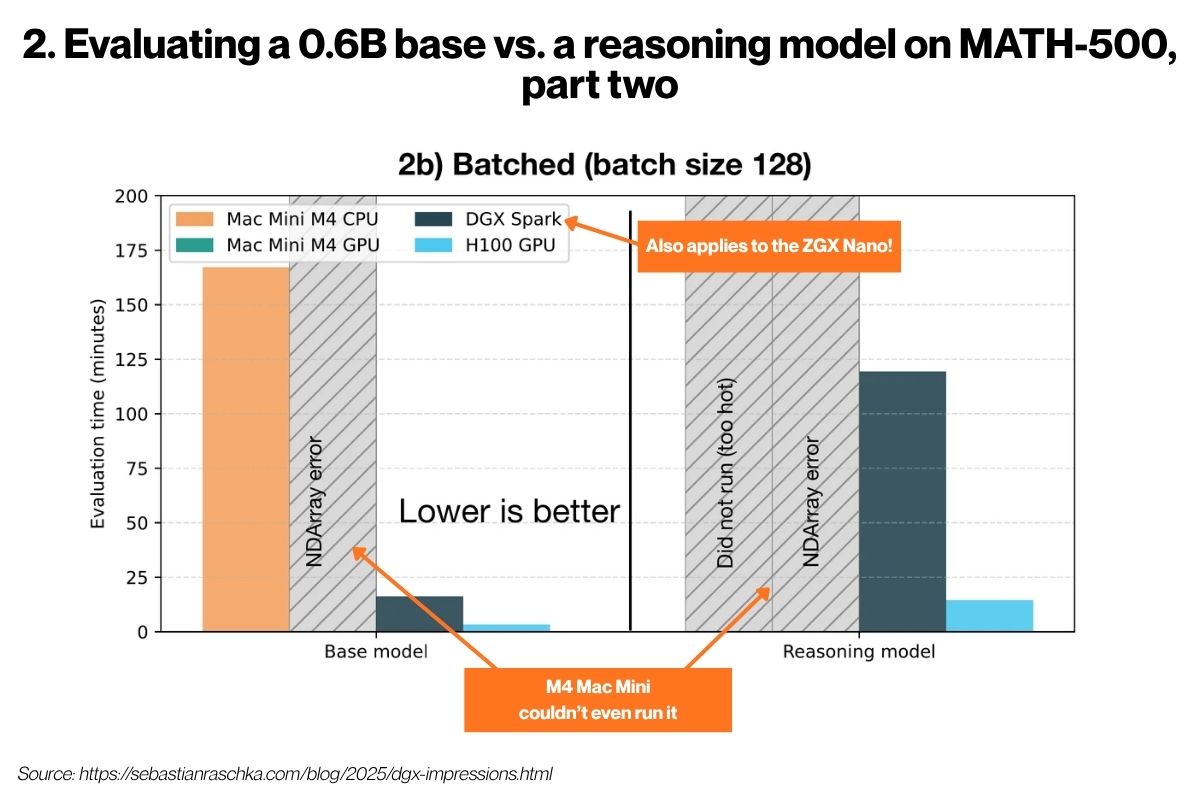

In the second version of the benchmark, the batch test, the model was served 128 questions at the same time, to simulate serving multiple users at once and to. test memory bandwidth and parallel processing.

This is a situation where the H100 would vastly outperform the ZGX Nano thanks to the H100’s much better memory bandwidth. However, the ZGX Nano isn’t for doing inference at production scale; it’s for developers to try out their ideas on a system that’s powerful enough to get a better sense of how they’d operate in the real world, and do so affordably.

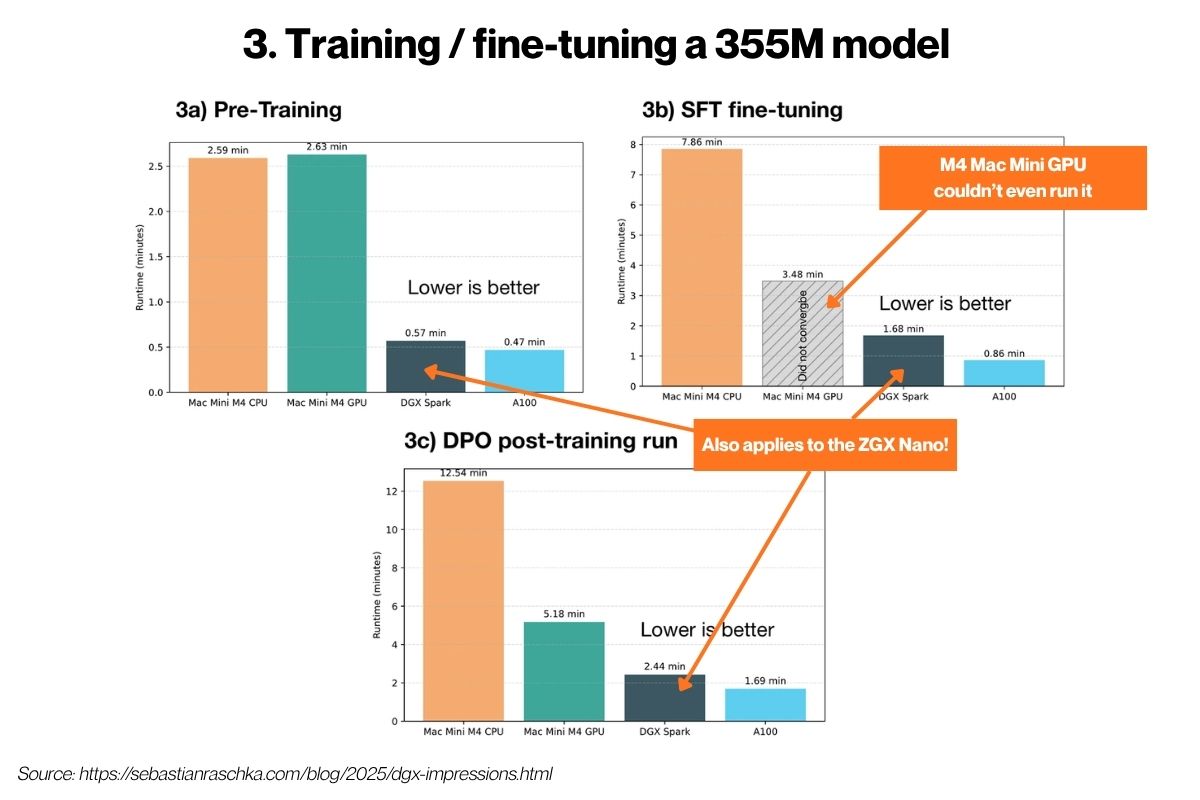

Finally, with the third benchmark, Rashcka trained and fine-tuned a model. Note that this time, the data center GPU was the A100 instead of the H100 due to availability.

Finally, with the third benchmark, Rashcka trained and fine-tuned a model. Note that this time, the data center GPU was the A100 instead of the H100 due to availability.

This benchmark tests training and fine-tuning performance. It compares how fast you can modify and improve an AI model on the Mac Mini M4 vs. the ZGX Nano’s twin vs. an A100 GPU. He presents three scenarios in training and fine-tuning a 355 million parameter model:

- Pre-training (3a in the graphs above): Training a model from scratch on raw text

- SFT, or Supervised fine-tuning (3b): Teaching an existing model to follow instructions

- DPO (direct preference optimization), or preference Tuning (3c): Teaching the model which responses are “better” using preference data

All these benchmarks say what I’ve been saying: the ZGX Nano lets you do real model training locally and economically. You get a lot of bang for your ZGX Nano buck.

As with a lot of development workflows, where there’s a development database and a production database, you don’t need production scale for every experiment. The ZGX Nano gives you a working local training environment that isn’t glacially slow or massively expensive.

Want to know more? Go straight to the source and check out Raschka’s article, DGX Spark and Mac Mini for Local PyTorch Development.

And with this article, I end my stint as the “spokesmodel” for the ZGX Nano. It’s not the end of my work in AI; just the end of this particular phase.

Keep watching this blog, as well as the Global Nerdy YouTube channel, for more!

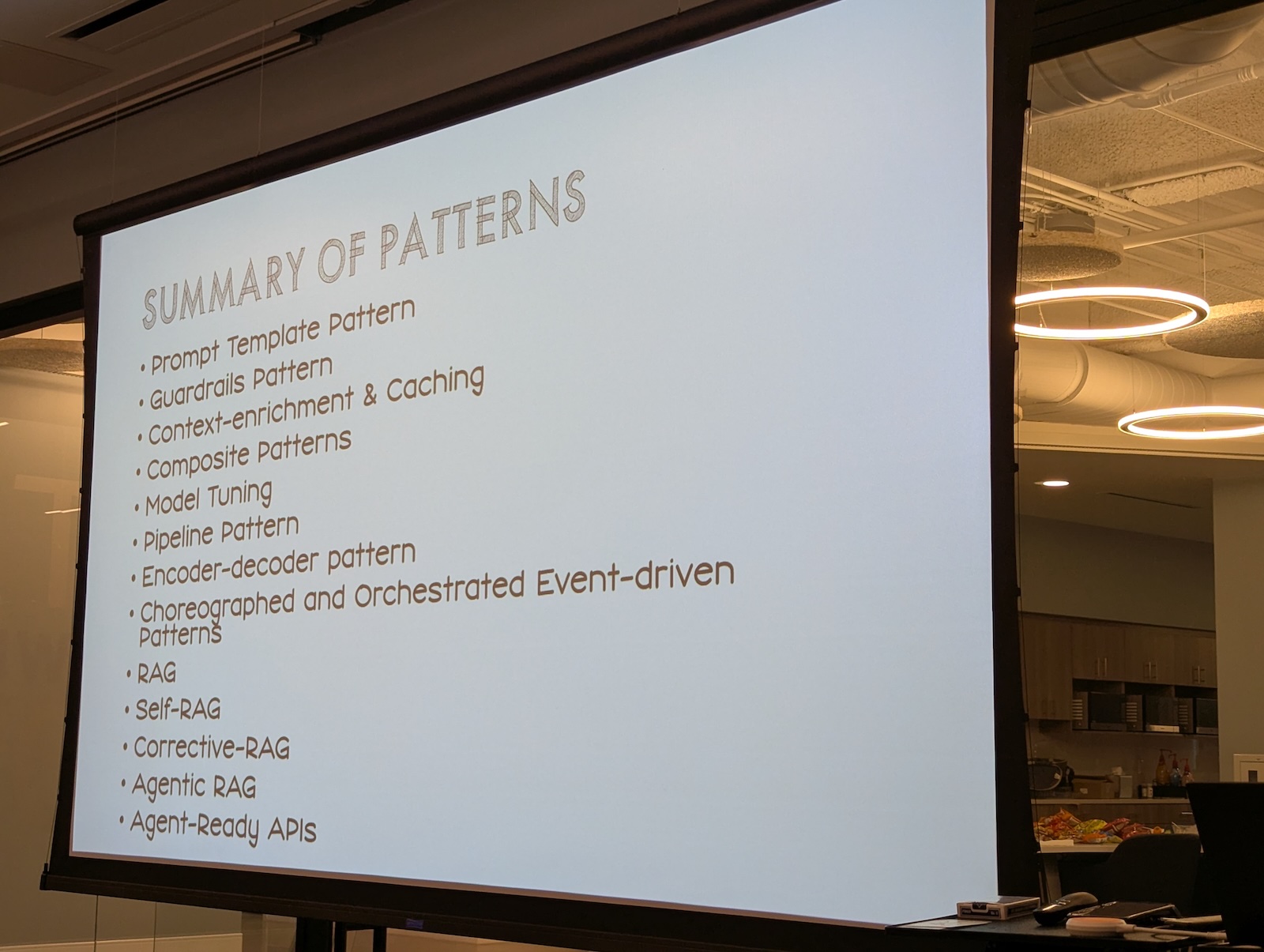

And once the presentation was done, a number of us reconvened at Colony Grill, the nearby pizza and beer place, where we continued with conversations and card tricks.

And once the presentation was done, a number of us reconvened at Colony Grill, the nearby pizza and beer place, where we continued with conversations and card tricks.