Click the photo to see it at full size.

I’m already on disk 479!

(By the way, if you want to know how to make Windows 8.1 boot straight to the desktop, check out my article on the topic.)

Click the photo to see it at full size.

I’m already on disk 479!

(By the way, if you want to know how to make Windows 8.1 boot straight to the desktop, check out my article on the topic.)

When I do something, I like to do it big. When I blow a technical interview, I don’t do it with two programmers working out of a cafe; I do it with effing Google.

My friend Enrico Bianco, who works at Google, heard that I was looking for other opportunities.

“There’s openings for developer advocate positions, and I think you’d be good at it,” he said in a Facebook chat. “You’re the only person who’s ever managed to make me reconsider my opinion that Microsoft is evil.”

I sent him my resume, and he submitted it a few days later. A mere 48 hours after that, I was contacted by someone at Google HR who asked “How soon can you be ready for a phone interview?”

I had that phone interview yesterday afternoon at 2:30, conducted by a Google developer advocate. He was quite personable, as a tech evangelist should be, and I was in my home office, on my own computers, and feeling quite comfortable. It should’ve gone off without a hitch, but instead, it went like this:

The interview started off well. My resume, which is essentially a cut-and-paste from my LinkedIn profile, is a pretty good one for someone seeking a developer evangelist / advocate / advisor position, and I’ve got my answers about what I’ve done and what I’ve learned down to the point where I can do them on autopilot.

With the initial interview out of the way, it was time for a little programming test. For developer advocates, this is a less difficult test than for those who do actual production coding, and in an attempt to ramp up my skills and build a portfolio, I’ve been doing at least an hour of iOS coding after work on most days. The purpose of this test was to see if I could code at all, and he would’ve been well within his rights to hit me with FizzBuzz.

“Time for the coding test. What language would you like to do it in?”

“How about Ruby?” I answered. I picked it and opened irb in a terminal window so that I could double-check my work.

“My Ruby’s a little rusty,” he said, “I’ve been doing more Python these days.”

Score one for my Batman-like strategic thinking:

I’ve heard that the languages in general use at Google are C++, Python, Java, and JavaScript; going with Ruby meant that he wouldn’t go all “language lawyer” on me. It became clear to me that I’d made the right choice when he tried to use __init__ as the name of a class constructor (that’s a Pythonism).

He typed a class like the one below into a Google doc. This is a cleaned-up, working version of what was typed:

# Cleaned-up working version of the class

# that he typed into Google Docs

class MiniGoogle

attr_accessor :index

def initialize

@index = {}

end

def add_to_index(url, body)

@index[url] = body

end

end

“Let’s say I’m making a cheap clone of Google,” he said. “And I’m using this class to store an index of pages by their URLs.” It was a rather Googly example, and it made sense: some client code crawls the web and records the URLs and content of the pages it crawls into an instance of MiniGoogle with add_to_index. He then typed the following:

def search(term) end

“Finish this search method,” he said. “It should return only those pages containing the search term.” “Seems straight-forward enough,” I said, and got to work. I couldn’t remember the name of the Ruby string method for determining if a string was a substring of another string. Luckily, I’d already had ruby-doc.org open, but the brain just wasn’t working. I searched through the documentation for the String class, probably scrolling past index at least two or three times before finally spotting it, thinking out loud for the benefit of my interviewer. In the end, I typed up something like this into the Google doc:

# My lame attempt

def search(term)

results = []

@index.each do |item|

if item.value.index(term)

results << [url, body]

end

end

end

The code above won’t work at all. I’d completely forgotten how you run a hash through a block in Ruby, and I’d also forgotten to return the result array. If I’d looped through the dictionary properly, the code still wouldn’t work, as it would just return the last value it referenced, namely @index — the entire collection of page URLs and their contents. Duh. Here’s code that works…

# This works, but it's wrong for other reasons

def search(term)

results = []

@index.each do |url, body|

if body.index(term)

results >> [url, body]

end

end

results

end

Once I was done typing, the interviewer gave my code a quick glance and said “You know, I was kind of hoping you’d do it another way, say using select.”

That’s when I got this feeling:

Not only is using select a more elegant way to solve the problem, but it’s exactly the approach you want to take in an interview with Google. When your bread and butter is crunching through large amounts of data with MapReduce, it only makes sense that you tend to take a more functional approach and think in terms of single-operation mapping, filtering, folding, and sorting. Once upon a time, my job was to be able to get inside programmers’ heads and know how they approached problems and why, and I completely forgot to do that.

I could blame my “let’s iterate through the hash and perform a test on each element as we go” approach on all the coding I’ve been doing lately has been in Objective-C (which doesn’t have all of Ruby’s functional niceties), but I have no excuse for blowing this. I’ve actually written a whole series of articles on the power of Ruby’s Enumerable module, including the select method (and what I think was a pretty clever explanation of fold).

I thrashed about on the Google doc, finally writing something like this in half-pseudocode:

# Wrong

def search(term)

@index.select{|item| item.value.index(term)}

end

As Murphy’s Law would have it, after the call, I whipped this up in seconds:

# Right, but too late to be useful for anything

# other than a code example in the blog entry

# documenting my FAIL

def search(term)

@index.select{|url, body| body.index(term)}

end

After that disastrous coding-in-a-Google-doc exercise, it was back to more Q & A, with me asking my interviewer questions, such as what a “typical” day for him was like (and yes, developer evangelism is so all over the map that there are few “typical” days).

I also asked him a number of questions about what Googly life is like; after all, I sure as hell wasn’t going to experience it after that interview.

I’ve hosted a number of “FailCamp” events, which are big confessionals where you stand in front of an audience and tell them your best story about FAIL, and then the lessons that you took from that experience.

I can’t blame it on nervousness coding in front of others, because I used to do that all the time. Anyone who’s seen my “Biebersmash” Windows Phone game development tutorial presentation knows that I start with an empty Visual Studio file and live-code it in front of an audience.

While my work for the past year has involved little or no coding, I can’t say that it’s been a while since I’ve written a program. In fact, I’ve been doing a little bit every day, working on my iOS programming and even managing to squeeze in a little Android. I’ve been writing iOS programming tutorial articles. I’m not what you’d call a seasoned pro yet, but I can make apps that actually work.

I am terribly out of Ruby practice. In the interview, I found myself looking up the simplest of things in the Ruby documentation. Dead air is deadly during an interview, which meant splitting my attention between looking up information and keeping the conversation going with the interviewer, which just slowed me down. If I could do it again, I’d love to prepare by noodling with Ruby, just to harness the power of habit and make sure I had my “sea legs” for the interview.

I’m going to take the philosophical approach to this. First, it’s gratifying that I could land the interview and that they wanted to talk to me rather quickly. There’s also some wisdom offered to me by computer science professor and C# book author Rob Miles: “What doesn’t kill you makes a great blog entry.”

Got a story of interview FAIL? Feel free to share it in the comments.

Be sure to read the follow-up article!

I’m helping out a friend who’s put together a SharePoint site for a customer. He’s an IT guy, not a developer, but he’s taken the site quite far using just the non-developer features in SharePoint, such as lists and workflows. He’s called on me to help him with a part that needs coding.

I can handle the C# programming part, but I have no idea how you go about sticking code into an existing SharePoint 2010 project and just the vaguest of memories of how to programatically access the contents of a SharePoint list. If someone can just give me some basic pointers on how to do that, I can handle the rest of the programming tasks.

Would any of youSharePoint developers — especially if you’re in the Toronto area, but hey, if you think you can help remotely, go for it — be able to help me out for an afternoon next week? (Yes, we can pay.) Get in touch with me either through the comments or via email at joey@joeydevilla.com.

The very first thing I do as soon as I boot into Windows 8 is click on the Desktop tile to put it into desktop, a.k.a. “useful” mode. While having to do that every time Windows starts is a First World Problem, I’m a First Worlder, and I can do without what David Pogue calls “TileWorld” getting in my way.

Luckily, Windows 8.1, which was just released (it’s free for Windows 8 users), has a number of features to help you get around some of the annoyances that got half-baked into Windows 8. One of them is a setting that lets you bypass TileWorld and boot straight into Desktop mode. You’ll only enter TileWorld when you tap the Windows key or click on the Start button.

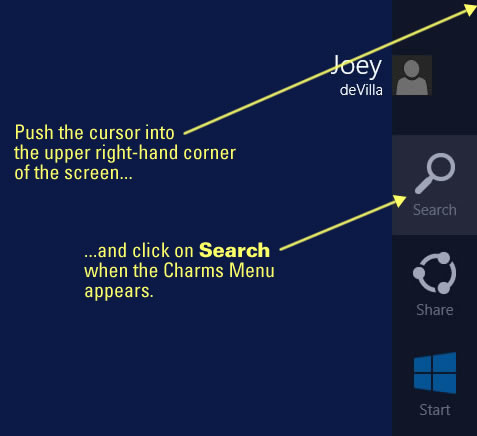

The “boot straight into Desktop mode” setting is tucked away in a control panel, but I’ll show you how to get to it. First, whether you’re in Desktop or TileWorld mode, push your cursor into the upper right-had corner of the screen. The Charms Menu will appear:

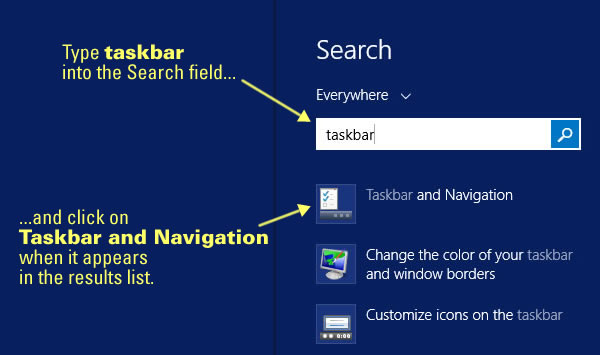

Click on the Search (magnifying glass) icon. A search text field will appear. Type taskbar into the text field:

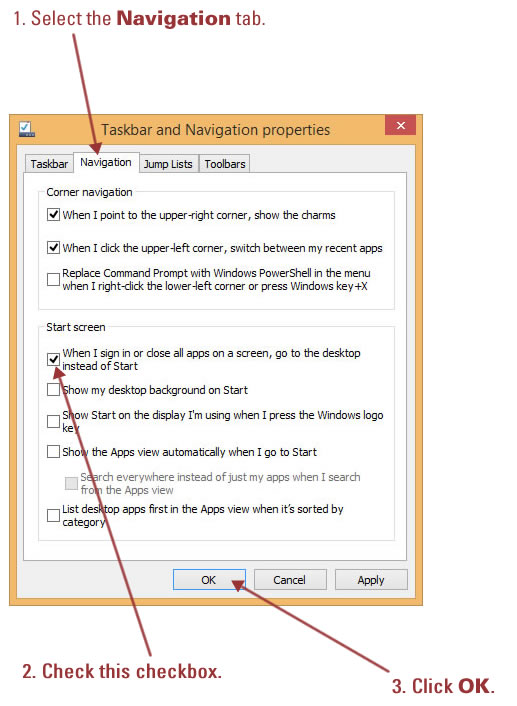

A number of search results for the term taskbar will appear. Click on the one marked Taskbar and Navigation. You’ll be taken to a control panel in desktop mode, which will look like this:

The setting you want is under the Navigation tab, so click on it. In the lower part of the window, there’ll be a section marked Start screen. The topmost checkbox in that section is marked When I sign in or close all apps on a screen, go to the desktop instead of Start. Check that checkbox, then click the OK button.

That’s it! The next time you log in, you’ll go straight to the Desktop instead of TileWorld.

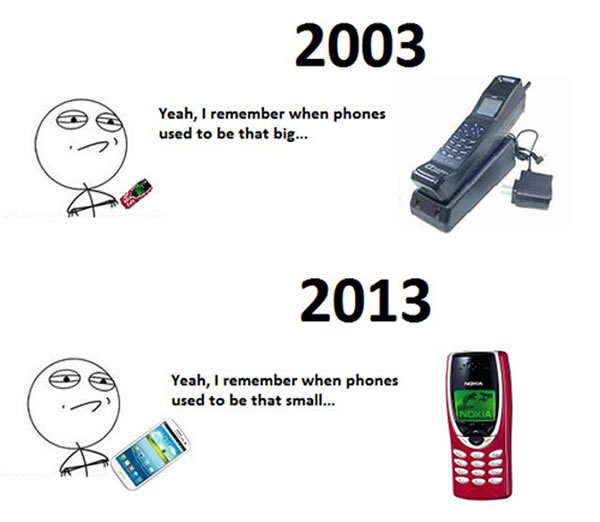

I still think that big smartphones and “phablets” are all part of a plot to bring back cargo pants…

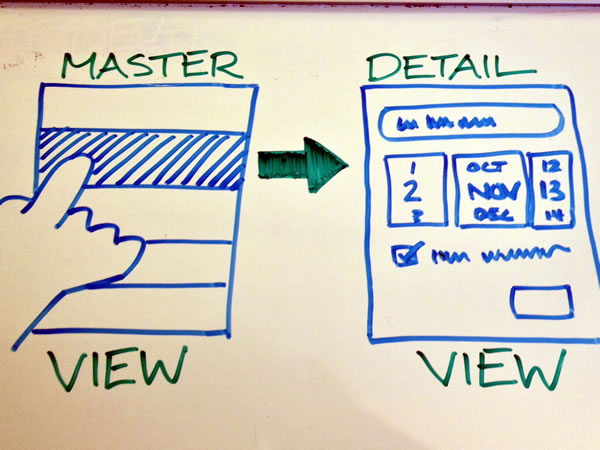

Here’s a UI pattern that appears all the time:

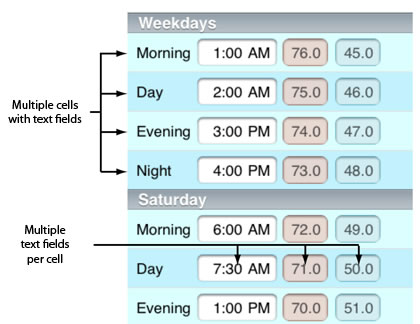

In this pattern, you see a list of items in a table view — a master view. If you tap on an item’s cell or some control inside that cell, you get taken to a detail view where you can edit that item’s details. It’s tried and true, but there are times when it would useful — and faster — to be able to edit these items right inside the table view, like the way it’s done in the table view below:

The article Editable UITableViewController in iOS-Blog shows you how to build such a table view and even provides the source files for a project in exchange for a tweet.

Over at RayWenderlich.com, there’s a two-part tutorial on using Auto Layout, for which author Matthijs Hollemans says:

Thankfully, Xcode 5 makes Auto Layout a lot easier. If you tried Auto Layout in Xcode 4 and gave up, then we invite you to give it another try with Xcode 5.

Part 1 covers the basics of Auto Layout using Interface Builder, and part 2 focuses on constraints.

“NSError is the unsung hero of the Foundation framework,” writes NSHipster’s Mattt Thompson in his latest article. “Passed gallantly in and out of perilous method calls, it is the messenger by which we are able to contextualize our failures.” In the article, he writes about NSError and where you’ll run into it: as a consumer and as a producer.

Microsoft’s original mantra was also their best, clearest mission statement, and one they pretty much accomplished: “A computer on every desk, and in every home”. As you can see from the shadows cast by the people in the bathroom stalls in the photo above, the age of mobile devices is all about “a computer in every hand, and in every can”.

It’s a great time to be in mobile technology, whether you’re building apps, providing services or selling mobile device antibacterial screen wipes.