Want to improve the title of Marc Andreessen’s screechy screed, The Techno-Optimist Manifesto? Easy. Just replace the misused word “optimist” with the more accurate “fascist.”

It reads like a supervillain monologue

From the opening sentence, “we are being lied to,” the essay takes bigger and bigger leaps into supervillain monologuing, with lines like “we are not victims, we are conquerors” [and yes, the italicization is Andreessen’s].

But the cherry on this shit sundae — and my personal favorite — is the line “We are not primitives, cowering in fear of the lightning bolt. We are the apex predator; the lightning works for us.” That sounds exactly like Marvel Comics’ Doctor Doom!

The “enemies list” that appears two-thirds of the way into the polemic seemed hilarious at first, but then you realize “Oh shit, he’s serious.” Naming “trust and safety,” “tech ethics,” and “risk management” as things to be opposed is the kind of thing an old Saturday morning cartoon villain would do. I’m reminded of the bad guys on Captain Planet, who declared war on clean water and air.

But as bad as the similarities to cartoon villainy are, the Techno-Optimist Manifesto takes its inspiration from something far, far worse.

The Futurist Manifesto

The real red flag is this paragraph, which you can find smack-dab in the middle of the essay, which is intentionally written with the structure of a poem:

To paraphrase a manifesto of a different time and place: “Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Technology must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.”

He could’ve made it much shorter by writing: Kneel before Zod!

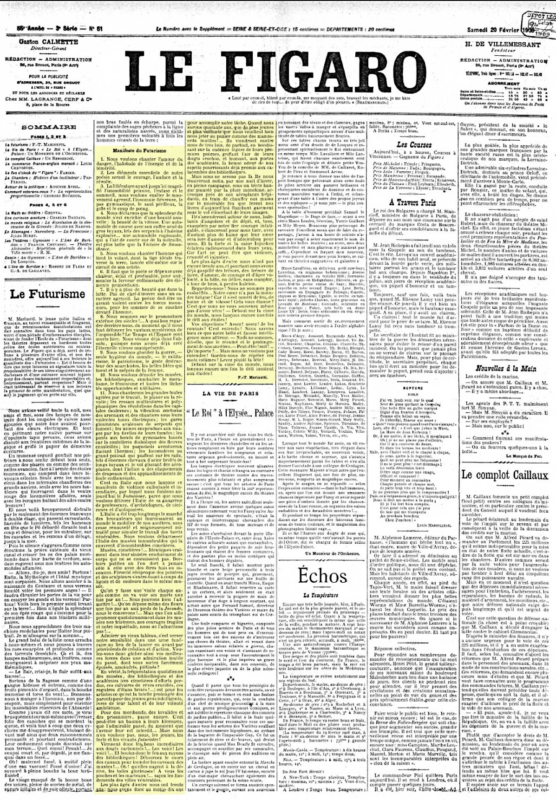

As a fan of the ’80s avant-pop synth band Art of Noise and a fan of industrial design, I knew what he was paraphrasing: The Futurist Manifesto, written by Italian poet and fascist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Here’s the paragraph that Andreessen paraphrased:

There is no longer any beauty except the struggle. Any work of art that lacks a sense of aggression can never be a masterpiece. Poetry must be thought of as a violent assault upon the forces of the unknown with the intention of making them prostrate themselves at the feet of mankind.

There’s a helluva lot of batshittery in Futurist Manifesto, and Marc Andreessen retrofitted it into the Techno-Optimist one.

Marinetti and Futurism

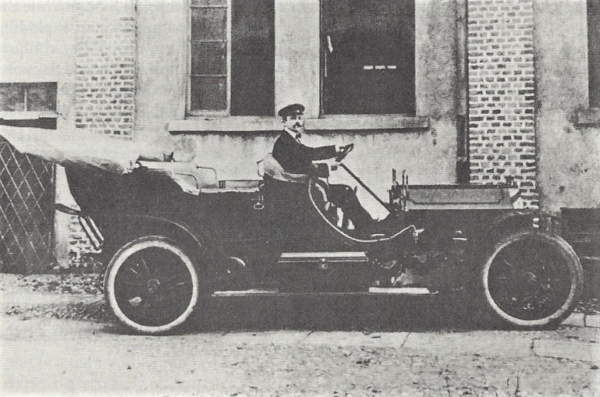

The Italian verision of Futurism started with a car accident.

Like the author of the Techno-Optimist Manifesto, the author of the Futurist Manifesto was in the top 1%. Marinetti had a very nice car — a Fiat Cabriolet — which was no small achievement, considering that it was 1908. (For reference, the first Fiat was produced in 1899, not even a decade before.)

In 1908, while driving home after a friend’s party outside of Milan, Marinetti was speeding and had to swerve to avoid hitting two cyclists. The car went into a ditch and was totaled.

In writing about the incident, he clearly paints himself as a lead-footed driver, describing himself as driving so fast that his car was: “hurling watchdogs against doorsteps, curling them under our burning tires like collars under a flatiron.”

(Remember, he was a rich, eccentric poet.)

Here’s how he described the crash:

The words were scarcely out of my mouth when I spun my car around with the frenzy of a dog trying to bite its tail, and there, suddenly, were two cyclists coming toward me, shaking their fists, wobbling like two equally convincing but nevertheless contradictory arguments. Their stupid dilemma was blocking my way—Damn! Ouch! … I stopped short and to my disgust rolled over into a ditch with my wheels in the air …

The lesson most well-adjusted people would’ve taken from the crash would be “don’t drive faster than you can maneuver,” but that requires one to be well-adjusted. Marinetti decided that it was a symbol of the new world (the car) destroying the old one (bicycles). It captured all the things that excited him: speed, technology, risk, and violence. He thought that they perfectly illustrated the rapidly changing world around him and were signs of a new everything — a new, more mechanical world, in a modern era where everything is fast and furious.

That led him to write the Manifesto in 1908. First published in 1909, it was meant to kick-start an art movement to transform the world — starting with Italy.

The main part of the Futurist Manifesto was written as a set of 11 statements, each one a short or one-sentence paragraph. Andreessen borrowed the style when writing the Techno-Optimist Manifesto:

- We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.

- The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and

revolt. - Literature has up to now magnified pensive immobility, ecstasy and

slumber. We want to exalt movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist. - We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath … a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

- We want to sing the man at the wheel, the ideal axis of which crosses the earth, itself hurled along its orbit.

- The poet must spend himself with warmth, glamour and prodigality to increase the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

- Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

- We are on the extreme promontory of the centuries! What is the use of looking behind at the moment when we must open the mysterious shutters of the impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the absolute, since we have already created eternal, omnipresent speed.

- We wish to glorify war — the world’s only hygiene — militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the libertarian, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.

- We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.

- We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure and revolt; the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals: the nocturnal vibration of the arsenals and the workshops beneath their violent electric moons: the gluttonous railway stations devouring smoking serpents; factories suspended from the clouds by the thread of their smoke; bridges with the leap of gymnasts flung across the diabolic cutlery of sunny rivers: adventurous steamers sniffing the horizon; great-breasted locomotives, puffing on the rails like enormous steel horses with long tubes for bridle, and the gliding flight of aeroplanes whose propeller sounds like the flapping of a flag and the applause of enthusiastic crowds.

“Come see the violence (and misogyny) inherent in the system!”

If you’re a reader of this blog, the word “Futurism” doesn’t sound so evil, and neither do three of its four aspects — I’m sure that like me, you like the concepts of speed, technology, and even at least a little risk.

And besides, how serious could they be about that fourth part, violence?

It turned out, very serious, at least in theory. Marinetti referred to war as “the world’s only hygiene.”

Here’s the full paragraph from the Manifesto where that bit about war appears:

We wish to glorify war — the world’s only hygiene — militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the libertarian, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.

I added the bold text for emphasis.

Once again, someone in the movies said it better — namely Arnold Schwarzenegger’s version of Conan the Barbarian:

In spite of their hatred for the calcified past, there was one long-standing tradition that Futurists were okay with: chicks ruin everything.

Futurism and fascism

If you ever find yourself examining an idea, approach, philosophy, or movement and asking “Is this fascist?”, you’ll find Umberto Eco’s Practical List for Identifying Fascists to be a handy checklist.

Futurism checks a lot (but not all) of Eco’s boxes:

- The cult of action for action’s sake

- Disagreement is treason

- Appeal to social frustration

- The enemy is both weak and strong

- Pacifism is trafficking with the enemy

- Contempt for the weak

- Everybody is educated to be the hero

- Selective populism

Futurism’s big difference from fascism is how each views the past. Futurists see the past as a useless relic holding them back, while fascists revere it as a golden, halcyon era that they must bring back.

Their similarities eventually overrode their differences. In 1918, Marinetti would form the Futurist Political Party, an extension of his artistic and social movement. A year later, they’d join another party, Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, whose name translates as “The Italian Fighting League.” That group would rename itself as the National Fascist Party in 1921. You might be familiar with their founder’s name: Benito Mussolini.

It’s more honest to call it techno-fascism

Let me show you what a real techno-optimist looks like:

I live, work, and play with technology — and with boundless joy and hope for the future — to the point that I’m associated with a technology that has nothing at all to do with what I get paid to do:

Seriously — if you’ve ever seen me give a presentation, you know what I mean when I say “techno-optimist.”

The Techno-Optimist Manifesto is heavy on the techno, and incredibly light on optimism. Yes, there’s a belief that the future could be better, but in that belief is the constant “j’accuse!” that if you’re not onside, you are the enemy — or at least a murderer.

That’s not optimism, but it is futurism. And you know where futurism leads.

Wired had an article in April 2019 titled When Futurism Led to Fascism—and Why It Could Happen Again, where they looked at futurism and asked:

Does any of this sound familiar? Disruption? Moving fast (and perhaps breaking things)? The rejection of history? Today’s most vocal voices in tech might not communicate their values with the same aplomb as the Italian poets, but they’re often saying the same kinds of things.

The article goes on to provide some examples of futurism’s ideas, expressed by today’s techbros, including Waymo’s cofounder Anthony Levandowski talking about how little he values history (“In technology, all that matters is tomorrow”) and “Google Memo” author James Damore’s claim that the gender gap in tech exists because men and women “biologically differ”.

Beware of venture capitalists writing manifestos

Manifestos written by people in positions of privilege tend to be cringeworthy, whether it’s James Damore’s “Google Memo”, Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, or Andreessen’s latest word salad.

In the end, Andreessen’s essay is just a long-form version of his tweet from December 3, 2022, which is just him saying “Let me do what I want, and stop getting in my way.”

I’m all for techno-optimism, but not the kind Andreessen’s selling.

2 replies on “The ugly manifesto behind the “Techno-Optimist Manifesto””

Truth is he provides internally a perfect refutation of his diatribe.

Richard Feynman:“Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts.” presumably Andreeson & co included.

And, “I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.”

Nothing more true in the entire thing.

Thank you. I stumbled,o your post searching Andreeson and fascism, having listened to Atlantic podcast a day ago

I see this as a great explanation of our present culture Andreeson an autocrat in tech, as is Musk, and many political

leaders worldwide seem eager to behave that way