Sometimes, it feels as if we spend more time in the latter state.

Thanks to Bil Simser for the find!

Sometimes, it feels as if we spend more time in the latter state.

Thanks to Bil Simser for the find!

I’ve been seeings reports from friends on Facebook and Twitter of warnings about using Samsung Galaxy Note 7 devices on flights.

Sutha Kamal, VP Technology Strategy for Technicolor, whom I know from DemoCamp Toronto, was on a KLM flight this morning. He posted on Facebook that one of the safety announcements was “It is strictly forbidden to turn on or charge your Samsung Galaxy 7 phone on this place”. I wonder how actively they had the flight crew looking for Galaxy Note 7s (and not Galaxy 7s, which don’t have the battery problem), what with everything else they have to do.

In response to Sutha’s post, Stuart MacDonald, principal at his Toronto-based consulting company said that Air Canada is doing gate checks for Galaxy Note 7s, and another friend of Sutha’s said that United did the same last Friday.

Farhan Thawar, formerly Mobile CTO and VP Engineering at Pivotal Labs, and currently co-founder of a startup in stealth mode, tweeted this:

Flight attendant just reminded us that @samsung Galaxy Note 7 devices must be completely turned off for this flight @AirCanada

— Farhan Thawar (@fnthawar) September 13, 2016

From there, I decided to search Twitter and found similar reports:

New York Times tech reporter Mike Isaac tweeted this:

Have been warned THREE separate times about the Samsung galaxy note 7 exploding before this flight. Worst ad campaign ever

— ಠ_ಠ (@MikeIsaac) September 13, 2016

Adobe’s principal graphic designer Khoi Vinh tweeted:…

About to board a flight and they made an announcement specifically about the Galaxy Note 7: “Do not power it on if you have one.”

— Khoi Vinh (@khoi) September 10, 2016

and he blogged about it as well.

Brian Behlendorf, executive director at the Hyperledger Project, had this to say earlier today:

On a plane about to take off. Twice they have warned people not to charge or use Galaxy Note 7s on the flight. Wow.

— brianbehlendorf (@brianbehlendorf) September 14, 2016

From Rajat Agrawal, BGR India and Mashable India editor:

Finally heard the warning about not using or charging Samsung Galaxy Note 7 on a flight. This is terrible for Samsung.

— Rajat Agrawal (@rajatagr) September 14, 2016

Buzzfeed’s Anne Helen Petersen:

wow Delta isn’t allowing Galaxy Note 7 phones in checked baggage or to be turned on at any time during flight

— Anne Helen Petersen (@annehelen) September 12, 2016

And there’s this gem from @Pelangihani:

Me if I see anyone turn on or charge their Samsung Galaxy Note 7 on my flight. pic.twitter.com/6SuQVOjWBH

— Hani (@Pelangihani) September 14, 2016

Khoi Vinh summed it up quite well in his blog entry:

Potentially embarrassing and even dangerous technological flaws are a fact of life for every hardware company—they may be extremely rare, but they are an ever present risk. What sets the best companies apart from others is their ability to respond in a way that preserves their brand and wins back the trust of customers. Unfortunately, I can’t imagine a worse situation for Samsung than having what amounts to a public service announcement before every flight advising customers not to use your product.

Looking for some programming puzzles to test your skill? Try return true to win, a site that challenges you to complete the JavaScript functions it gives you to return the value true. It will also remind you how full of “wat” JavaScript is.

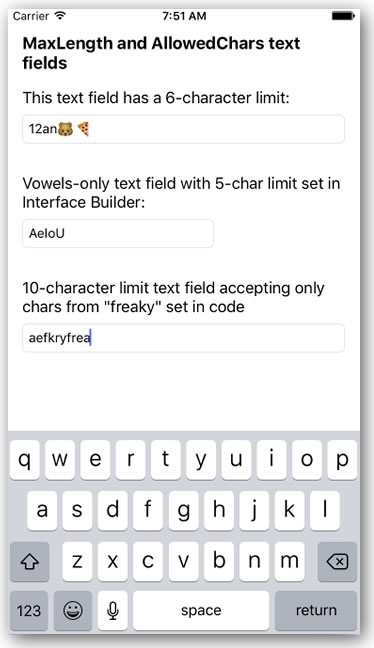

In the previous article in this series, we added a long-missing feature to iOS text fields: the ability to limit them to a maximum number of characters, specifying this limit using either Interface Builder or in code. In this article, we’ll add an additional capability to our improved text field: the ability to allow only specified characters to be entered into them.

MaxLengthTextField: A quick review

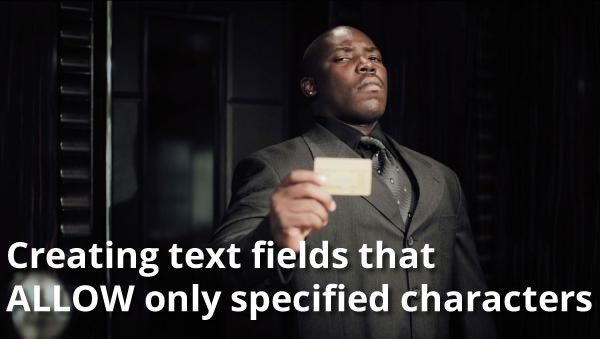

A screen shot of the example app demonstrating our improved text field class, MaxLengthTextField, in action. Download the project files for the app.

In the previous article, we subclassed the standard iOS text field, UITextField, to create a new class called MaxLengthTextField. MaxLengthTextField uses the following to give it the ability to limit itself to a set maximum number of characters:

UITextFieldDelegate protocol, giving it access to its textField(_:shouldChangeCharactersIn:replacementString:) method, which is called whenever is called whenever user actions change the text field’s content. This method lets us intercept this event, and determine whether or not the changes should be allowed. If the method returns true, the changes are allowed; otherwise, it forbids the change, and the text field acts as if the user didn’t do any editing.characterLimit, which stores that maximum number of characters allowed into the text field.maxLength, which is used to get and set the value stored in characterLimit. maxLength is marked with the @IBInspectable attribute, which allows its value to be read and set from within Interface Builder.textField(_:shouldChangeCharactersIn:replacementString:) determines the length of the string that would result if the user’s edits to the text field were to be made. If the resulting number of characters is less than or equal to the set maximum, the method returns true and the changes are allowed. If the resulting number of character is greater than the set maximum, the method returns false, and the changes do not take place.We’ll build our new text field class, which we’ll call AllowedCharsTextField, as a subclass of MaxLengthTextField. Before we do that, we need to tweak the MaxLengthTextField class so that it’s easier to subclass.

MaxLengthTextField, just a littleIf you didn’t work with any of the code from the previous article, don’t worry — this article will provide you with the code for MaxLengthTextField. In fact, it’ll provide you with a slightly tweaked version, shown below.

Create a new project, and within that project, create a Swift file named MaxLengthTextField.swift, which you should then fill with the following code:

import UIKit

class MaxLengthTextField: UITextField, UITextFieldDelegate {

private var characterLimit: Int?

required init?(coder aDecoder: NSCoder) {

super.init(coder: aDecoder)

delegate = self

}

@IBInspectable var maxLength: Int {

get {

guard let length = characterLimit else {

return Int.max

}

return length

}

set {

characterLimit = newValue

}

}

func textField(_ textField: UITextField, shouldChangeCharactersIn range: NSRange, replacementString string: String) -> Bool {

guard string.characters.count > 0 else {

return true

}

let currentText = textField.text ?? ""

let prospectiveText = (currentText as NSString).replacingCharacters(in: range, with: string)

// 1. Here's the first change...

return allowedIntoTextField(text: prospectiveText)

}

// 2. ...and here's the second!

func allowedIntoTextField(text: String) -> Bool {

return text.characters.count <= maxLength

}

}

This version of MaxLengthTextField differs from the version in the previous article in two ways, each one marked with a numbered comment.

The original version of the textField(_:shouldChangeCharactersIn:replacementString:) method contained all the logic of determining whether or not the text field should accept the changes made by the user:

true.Steps 1 and 2 are applicable to any text field where we want to limit input to some criteria. Step 3 is specific to a text field where we want to limit input to a set maximum number of characters. We’ve factored step 3 into its own method, which returns true if the prospective text meets some criteria. There’s a method to this madness, and it’ll become clear once we build the AllowedCharsTextField class.

MaxLengthTextField to make AllowedCharsTextFieldAdd a new a Swift file to the project and name it AllowedCharsTextField.swift. Enter the following code into it:

import UIKit

import Foundation

class AllowedCharsTextField: MaxLengthTextField {

// 1

@IBInspectable var allowedChars: String = ""

required init?(coder aDecoder: NSCoder) {

super.init(coder: aDecoder)

delegate = self

// 2

autocorrectionType = .no

}

// 3

override func allowedIntoTextField(text: String) -> Bool {

return super.allowedIntoTextField(text: text) &&

text.containsOnlyCharactersIn(matchCharacters: allowedChars)

}

}

// 4

private extension String {

// Returns true if the string contains only characters found in matchCharacters.

func containsOnlyCharactersIn(matchCharacters: String) -> Bool {

let disallowedCharacterSet = CharacterSet(charactersIn: matchCharacters).inverted

return self.rangeOfCharacter(from: disallowedCharacterSet) == nil

}

}

Here’s what’s happening in the code above — these notes go with the numbered comments:

allowedChars contains a string specifying the characters that will be allowed into the text field. If a character does not appear within this string, the user will not be able to enter it into the text field. This instance variable is marked with the @IBInspectable attribute, which means that its value can be read and set from within Interface Builder.MaxLengthTextField‘s allowedIntoTextField method lets us add additional criteria to our new text field type. This method limits the text field to a set maximum number of characters and to characters specified in allowedChars.String class to include a new method, containsOnlyCharactersIn(_:), which returns true if the string contains only characters within the given reference string. We use the private keyword to limit this access to this new String method to this file for the time being.AllowedCharsTextFieldUsing AllowedCharsTextField within storyboards is pretty simple. First, use a standard text field and place it on the view. Once you’ve done that, you can change it into an AllowedCharsTextField by changing its class in the Identity Inspector (the inspector with the ![]() icon):

icon):

If you switch to the Attributes Inspector (the inspector with the ![]() icon), you’ll be able to edit the text field’s Allowed Chars and Max Length properties:

icon), you’ll be able to edit the text field’s Allowed Chars and Max Length properties:

If you prefer, you can also set AllowedCharsTextField‘s properties in code:

// myNextTextField is an instance of AllowedCharsTextField myNewTextField.allowedChars = "AEIOUaeiou" // Vowels only! myNewTextField.maxLength = 5

MaxLengthTextField and AllowedCharsTextField in action

If you’d like to try out the code from this article, I’ve created a project named Swift 3 Text Field Magic 2 (pictured above), which shows both MaxLengthTextField and AllowedCharsTextField in action. It’s a simple app that presents 3 text fields:

MaxLengthTextField with a 6-character limit.AllowedCharsTextField text field with a 5-character maximum length that accepts only upper- and lower-case vowels. Its Max Length and Allowed Chars properties were set in Interface Builder.AllowedCharsTextField text field with a 10-character maximum length that accepts only the characters from “freaky”. Its maxLength and allowedChars properties were set in code.Try it out, see how it works, and use the code in your own projects!

You can download the project files for this article (68KB zipped) here.

In the next installment in this series, we’ll build a slightly different text field: one that allows all characters except for some specified banned ones.

Join us on Tuesday, September 27th for Tampa iOS Meetup, where we’ll cover making sticker packs and apps for iOS 10’s overhauled iMessage app!

With the newly-released iOS 10, the iMessage app will introduce a boatload of new features, including the ability for users to really customize their messages with:

One really interesting thing about iMessage sticker packs is that you don’t do any coding to create them! If you’ve got art skills but no coding skills, stickers are your chance to put something in the App Store.

For those of you with coding skills, you’ll find iMessage apps interesting — they’re apps that live within iMessage and extend its capabilities! You can build apps that use iMessage as a platform so that friends can play games, send customized messages, make payments, and more! We’ll show you how to get started writing iMessage apps.

Come join us at the Tampa iOS Meetup on Tuesday, September 27th at 6:30 p.m. and learn about making stickers and apps for iMessage, which promises to be a great new way to break into the iOS market.

You don’t even need coding skills to get something from this meetup. To make sticker packs, all you need is a Mac, Apple’s free Xcode software and a developer account (we’ll show you how to get these), and a little creativity. If you’re new to Swift but have some programming experience in just about any language, whether it’s Java, JavaScript, C#, Python, Ruby, or any other object-oriented programming language, you shouldn’t have any trouble following the iMessage apps presentation. We’ll make all of our presentation materials, and project files available at the end of the meetup so you won’t leave empty-handed!

Please note that this session of the Tampa iOS Meetup will take place at a new location: the Wolters Kluwer offices at 1410 North Westshore Boulevard (Tampa).

We’d like to thank Jamie Johnson for letting us use his office, Energy Sense Finance for the past year. We couldn’t have done it without you!

You don’t actually need to bring anything to the meetup, but you can get even more out of it if you bring a Mac with Xcode installed (you can download it for free from Apple).

If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me at joey@joeydevilla.com.

That was quick: A mere day after the iPhone 7 announcement in which the much-rumored removal of the 1/8″ analog headphone jack turned out to be true, the wags at College Humor produced a pitch-perfect iPhone parody ad featuring a pretty good impression of a Jony Ive voice-over:

I laughed out loud at the part where they showed Jony Ive’s iCalendar, which has a couple of amusing scheduled items:

Click to see at full “al-yoo-minny-yum” size.

Hey, I still love my iPhone (and don’t forget, I run an iOS developer meetup), but if you must vent at me for blaspheming by posting this article, there is a comments selection below…

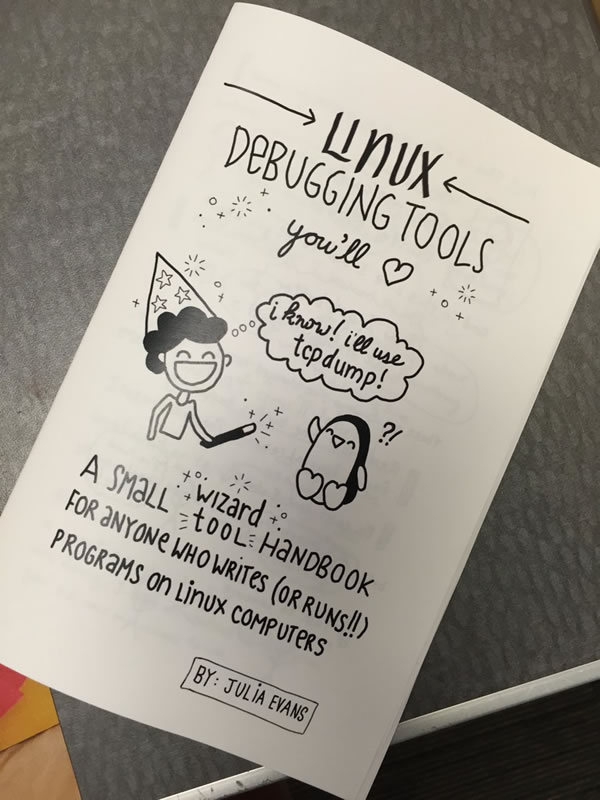

Solid advice from Julia Evans’ Twitter feed. Click to see the source.

If you’re a programmer (or hope to be one) and you’re not following Julia Evans (@b0rk) on Twitter, go and fix that mistake right now.

Her Twitter feed has the vibe of a zine — pronounced zeen — which is short for fanzine, which in turn is short for fan magazine. Before the web, fans of certain things — alt-rock or punk bands, cyberpunk, various cultural movements or social causes, jokes, whatever — would publish stapled-together photocopied publications as little do-it-yourself magazines:

Zines. Click on the photo to see the source.

Here’s a definition of zine in zine format:

Click the photo to see the source.

Zines came about when it was easier to get your hands on a photocopier and Letraset than a computer and printer that could print more than just text. By necessity, they featured a lot of hand-drawn, hand-lettered art and comics…

…and because they’re labors of love, they often feature material that you wouldn’t find in larger, more mainstream publications. Zines cover all sorts of topics, from underground culture and music to science and social responsibility…

Click to see at full size.

…and there’s at least one heavily-trafficked site that started off as a zine:

Julia’s actually up and made zines about programming, what with her zine on debugging your programs using strace and her upcoming one, Linux debugging tools you’ll ❤️ (pictured below):

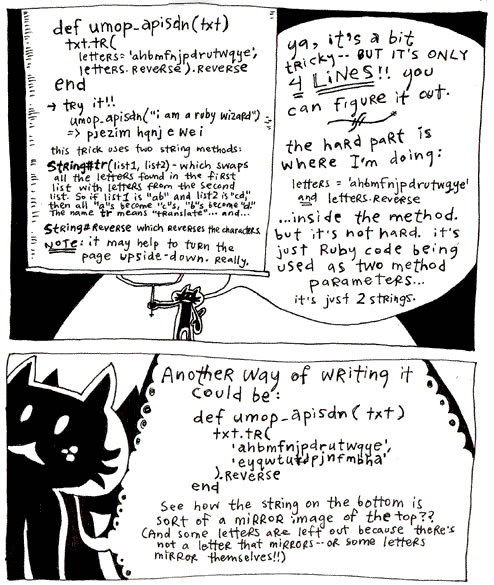

Here’s another gem from her Twitter feed:

Click to see the source.

I think she’s bringing back something that we lost when why the lucky stiff decided to pull a J.D. Salinger and disappear from the web:

But hey, this post is about Julia, so let’s end it with one more goodie from her Twitter feed!

Click to see the source.

Once again, if you haven’t added @b0rk to your Twitter feed, you’re missing out on some great stuff!