A quick recap

A couple of weeks ago, I posted an article that showed how to program an iOS text field that takes only numeric input or specific characters with a maximum length in Swift.

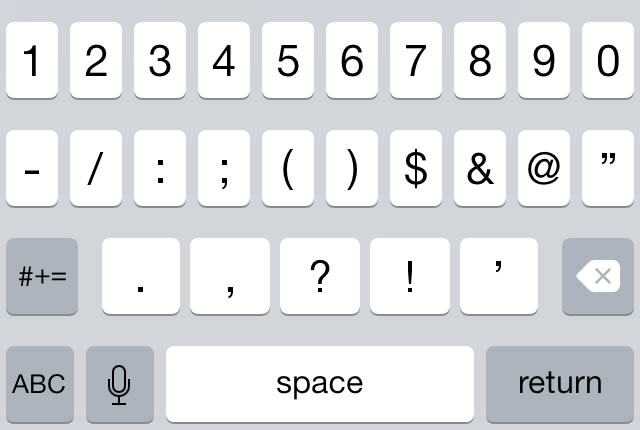

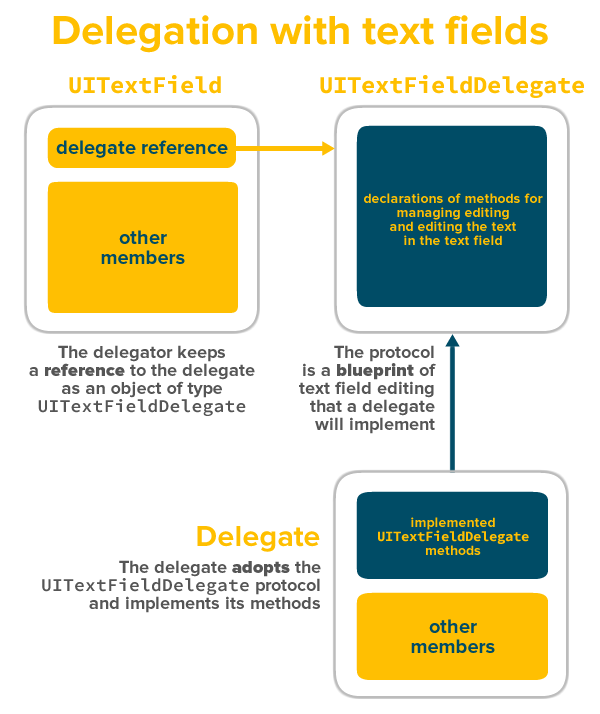

It covered the Delegate pattern (something you’ll use often in iOS development), introduced the UITextFieldDelegate protocol, and showed you how to use one of its methods, textField(_:shouldChangeCharactersInRange: replacementString:), to intercept the characters that the user inputs into text fields.

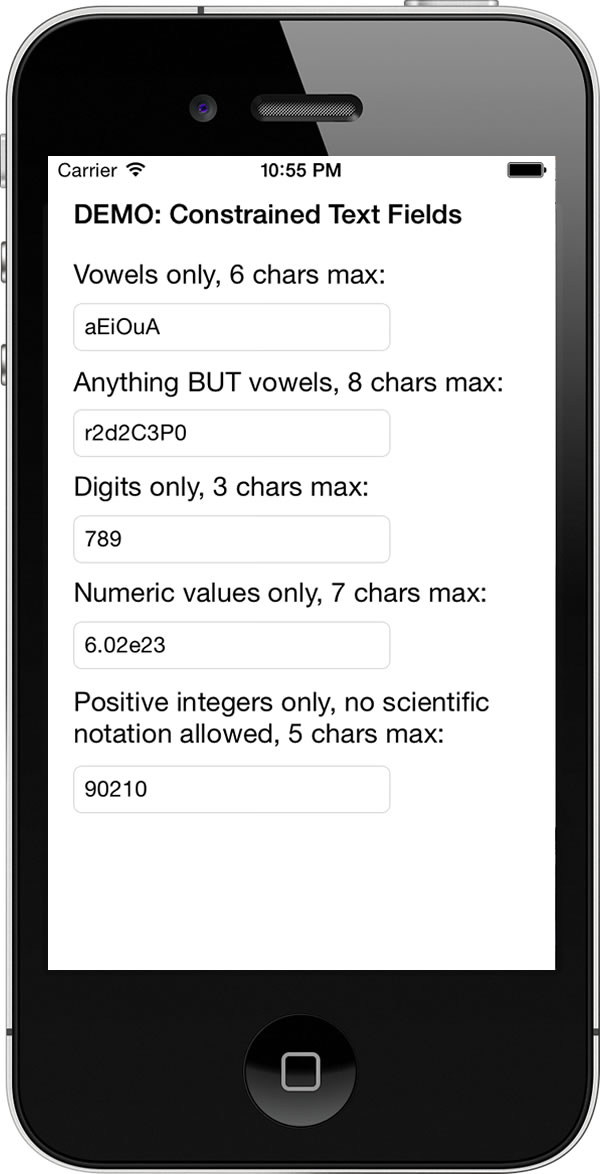

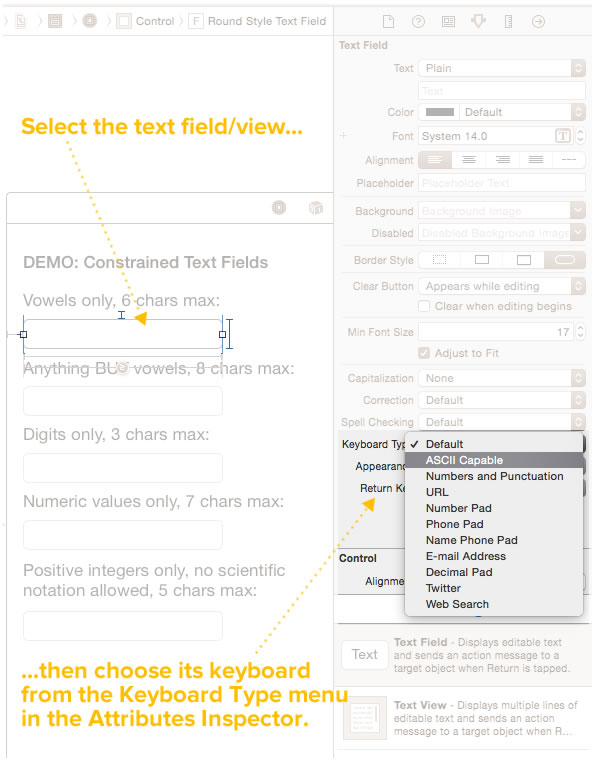

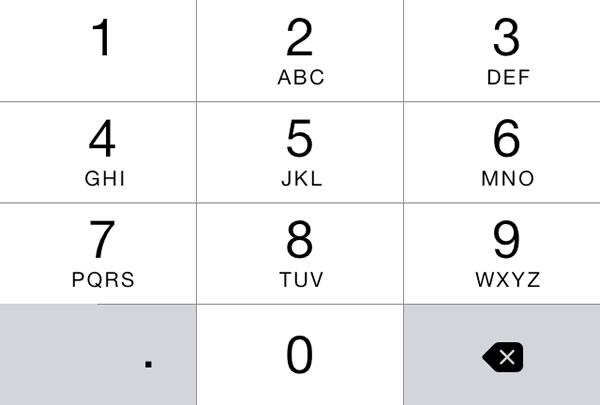

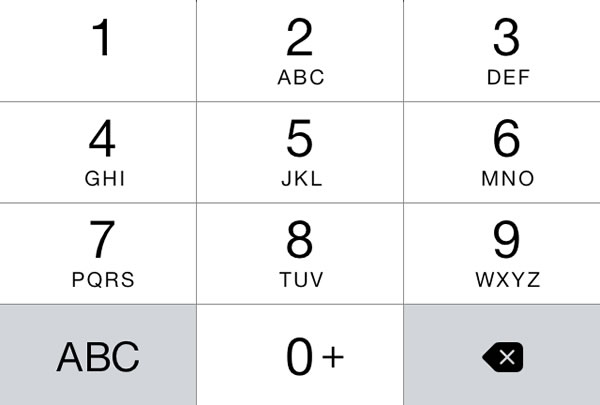

![]() The article included the Xcode project files for the featured app, ConstrainedTextFieldDemo. You can download it here [83K Xcode project and associated files, zipped]. When you run it, you’ll the screen pictured above, with text fields constrained so that they’d accept only characters from a specified set, or reject characters from a specified set.

The article included the Xcode project files for the featured app, ConstrainedTextFieldDemo. You can download it here [83K Xcode project and associated files, zipped]. When you run it, you’ll the screen pictured above, with text fields constrained so that they’d accept only characters from a specified set, or reject characters from a specified set.

Undocumented feature #1: Dismissing the keyboard when the user taps the “Return” key

One of the features that was included in the app but discussed only in passing was the dismissal of the keyboard when the user tapped the Return key. While this is convenient for the user, it’s not iOS’ default behavior. You have to watch for the event where the user taps the Return key, and then respond accordingly.

The UITextFieldDelegate protocol’s textFieldShouldReturn(textField: UITextField) method is called whenever the user taps the Return key while editing a text field. It accepts a single parameter, textField, which is a reference to the text field the user was editing when s/he tapped the Return key. It returns a bool — true if the text field should implement its default behavior for the Return key; otherwise, false otherwise. It’s where you should place code to intercept the Return key event.

What should that code be? If you remember only one thing from this article, let it be this:

The way to dismiss the iOS keyboard after the user is editing a text field is to make the text field resign its role as first responder.

What’s the first responder, you ask?

- The short answer is that the UI object that currently has the first responder role in iOS is roughly analogous to the UI object that currently has the focus in other systems (such as Android, HTML, and .NET).

- The long answer is that the first responder is the first view in the responder chain to receive many events. Most of the time, it’s the view in a window that an app deems best suited for handling an event. You can find out more by reading these Apple documents: Event Delivery: The Responder Chain and their

Responderobject documentation.

Take a look at code in the example app in my earlier article, particularly ViewController.swift.

Combining the textFieldShouldReturn(textField: UITextField) method and The One Thing You Should Remember From This Article, we get this method definition:

// Dismiss the keyboard when the user taps the "Return" key or its equivalent

// while editing a text field.

func textFieldShouldReturn(textField: UITextField) -> Bool {

textField.resignFirstResponder()

return true;

}

After all that preamble, the method itself seems pretty short and anticlimactic. This method lives in the ViewController class, which has adopted the UITextViewDelegate protocol…

class ViewController: UIViewController, UITextFieldDelegate {

…and in its viewDidLoad() method, it declared itself as the delegate of every text field in the corresponding view:

// Designate this class as the text fields' delegate

// and set their keyboards while we're at it.

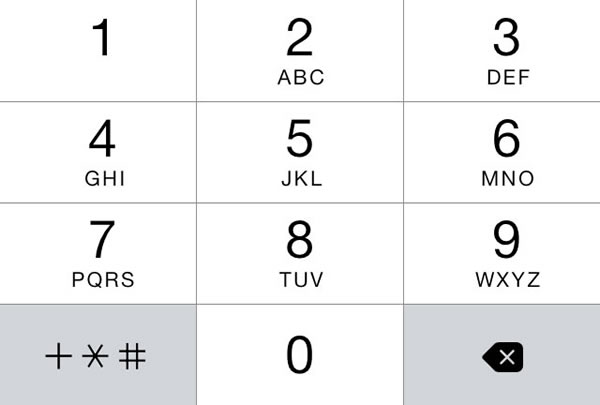

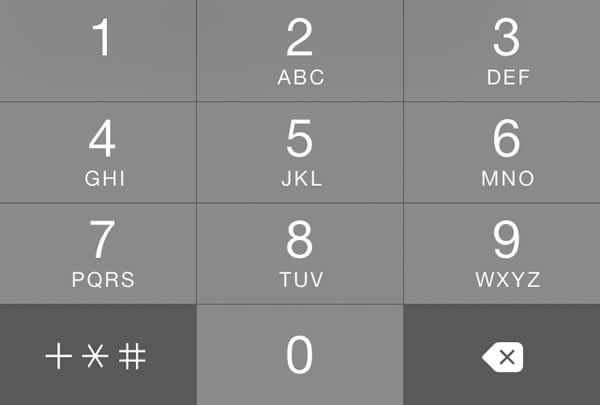

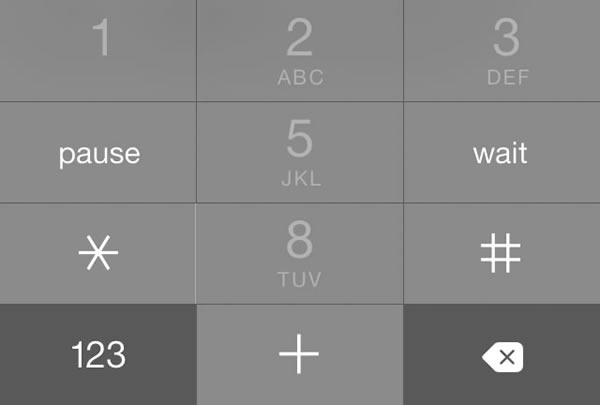

func initializeTextFields() {

vowelsOnlyTextField.delegate = self

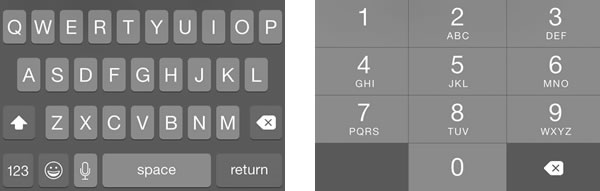

vowelsOnlyTextField.keyboardType = UIKeyboardType.ASCIICapable

noVowelsTextField.delegate = self

noVowelsTextField.keyboardType = UIKeyboardType.ASCIICapable

digitsOnlyTextField.delegate = self

digitsOnlyTextField.keyboardType = UIKeyboardType.NumberPad

numericOnlyTextField.delegate = self

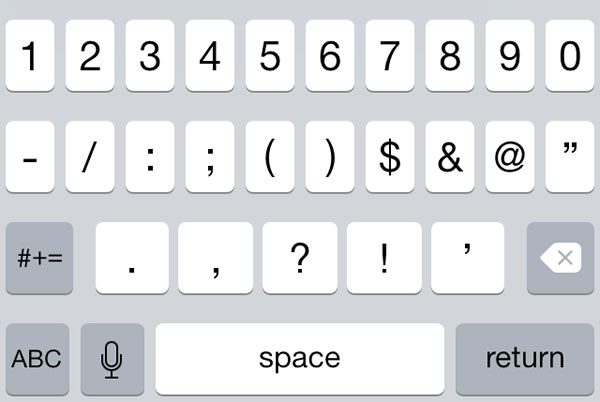

numericOnlyTextField.keyboardType = UIKeyboardType.NumbersAndPunctuation

positiveIntegersOnlyTextField.delegate = self

positiveIntegersOnlyTextField.keyboardType = UIKeyboardType.DecimalPad

}

All this setup means that whenever the user edits any of the text fields in the view — whether it’s vowelsOnlyTextField, noVowelsTextField, digitsOnlyTextField, numericOnlyTextField, or positiveIntegersOnlyTextField — and then hits the Return key, the textFieldShouldReturn(textField: UITextField) method gets called.

And when the textFieldShouldReturn(textField: UITextField) method, it does just two things:

- It tells the text field to resign its first responder role (by invoking its

resignFirstResponder()method). In this application, we want the keyboard to disappear when the user taps the Return key regardless of the text field, so we don’t bother trying to identify the text field; we simple calltextField.resignFirstResponder(). - Aside from dismissing the keyboard, we want the Return key to function as it normally would, so we have the method return

true, which states that text field should implement its default behavior.

Resources

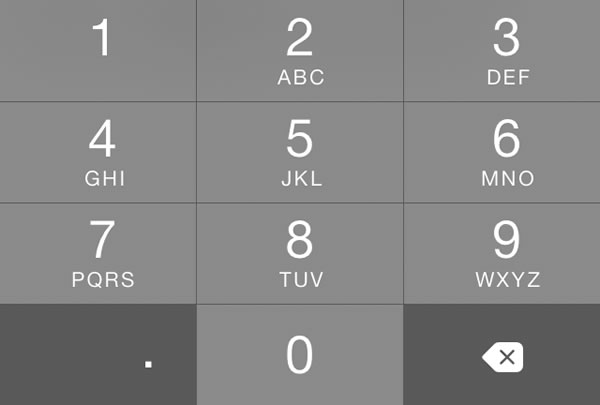

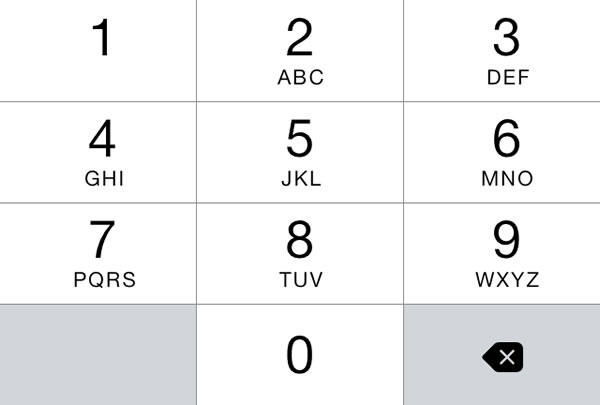

![]() Once again, here are the zipped project files for the demo project, ConstrainedTextFieldDemo [83K Xcode project and associated files, zipped].

Once again, here are the zipped project files for the demo project, ConstrainedTextFieldDemo [83K Xcode project and associated files, zipped].