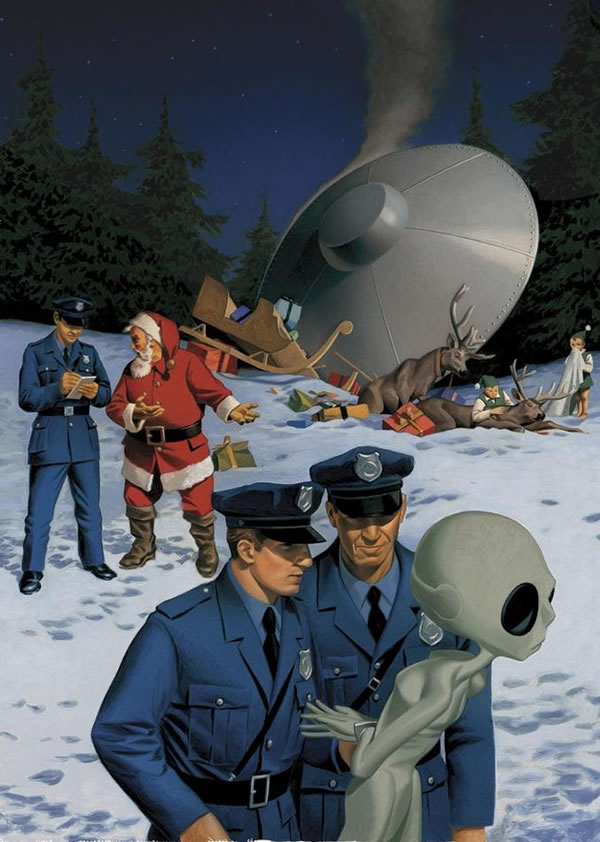

Have a safe and happy holiday!

All of us at GSG would like to wish you and your families a safe and happy holiday. We’d rather you didn’t get in the situation pictured above!

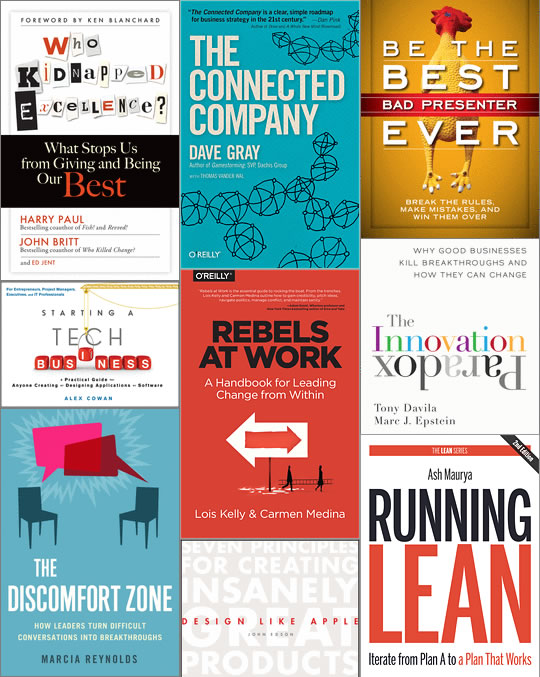

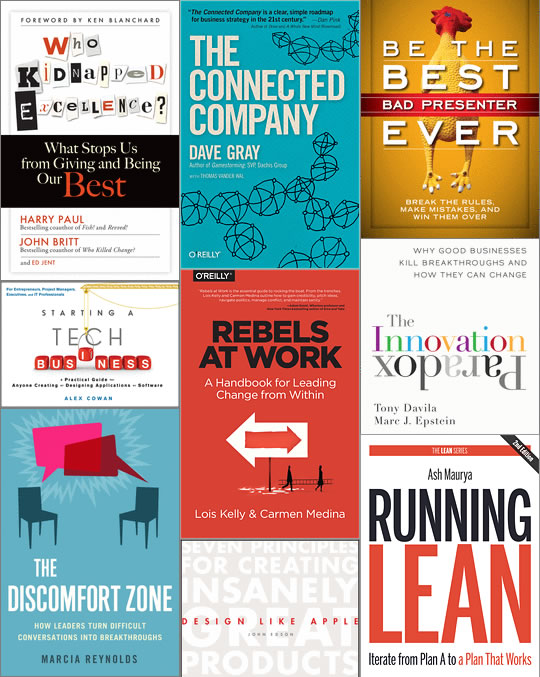

Save on great last-minute gifts at O’Reilly: 50% off ebooks and training videos and 40% off print books

O’Reilly make a good number of go-to books and videos for programmers, but they have a great selection of business books as well! Better still, they’re on sale for 50% off in electronic form (which you can get right away) or 40% off in print form until Friday, December 26 at 8:00 a.m. Eastern (GMT-5) / 5:00 a.m. Pacific (GMT-8)! Some notable books from their collection are:

- Be the Best Bad Presenter Ever: If you hate leading presentations and public speaking, this book is for you! Author Karen Hough debunks over a dozen myths about presenting, explains how practicing in front of a mirror makes you worse, why you should never end with questions, and tells stories about people who not only were able to become great presenters by being “bad” but actually came to enjoy it! Follow her wise and witty advice, and you’ll be able to tear up the old rules and embrace and develop your own style. You’ll be freed to be a living, breathing, occasionally clumsy human being whose enthusiasm is powerful and infectious.

- The Discomfort Zone: The Discomfort Zone is the moment when the mind is most open to learning. Author Marcia Reynolds says that it can prompt people to think through problems, see situations more strategically, and transcend their limitations. This book shows how to ask the kinds of questions that short-circuit the brain’s defense mechanisms and habitual thought patterns. The results: people are freed to find insightful and often profound solutions and get around the mental roadblocks holding them back. It features exercises and case studies will help you use discomfort in your conversations to create lasting changes and an enlivened workforce.

- Rebels at Work: Ready to stand up and create positive change at work, but reluctant to speak up? True leadership doesn’t always come from a position of power or authority. By teaching you skills and providing practical advice, this handbook shows you how to engage your coworkers and bosses and bring your ideas forward so that they are heard, considered, and acted upon.

- The Connected Company: In a world with social media, when your company’s performance runs short of what you’ve promised, customers can seize control of your brand message, spreading their disappointment and frustration faster than you can keep up. To keep pace with today’s connected customers, your company must become a connected company. That means deeply engaging with workers, partners, and customers, changing how work is done, how you measure success, and how performance is rewarded. It requires a new way of thinking about your company: less like a machine to be controlled, and more like a complex, dynamic system that can learn and adapt over time.

- Who Kidnapped Excellence? This book has only 5-star reviews on Amazon and explains personal and organizational excellence in the form of a crime thriller. Excellence (personified) has been kidnapped, and Leadership pulls together a team made up of Passion, Flexibility, Communication, Competency, and Ownership to carry out the rescue. The problem: Average may be trying to replace that team with lesser people: N. Different, N. Ept, N. Flexible, Miss Communication, and Poser.

At half price and in ebook form, many of the books go for just above 10 bucks apiece. Just go to shop.oreilly.com and use the discount code HDPDNY at checkout!

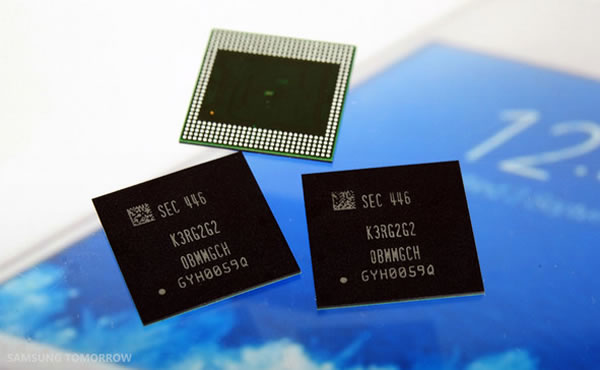

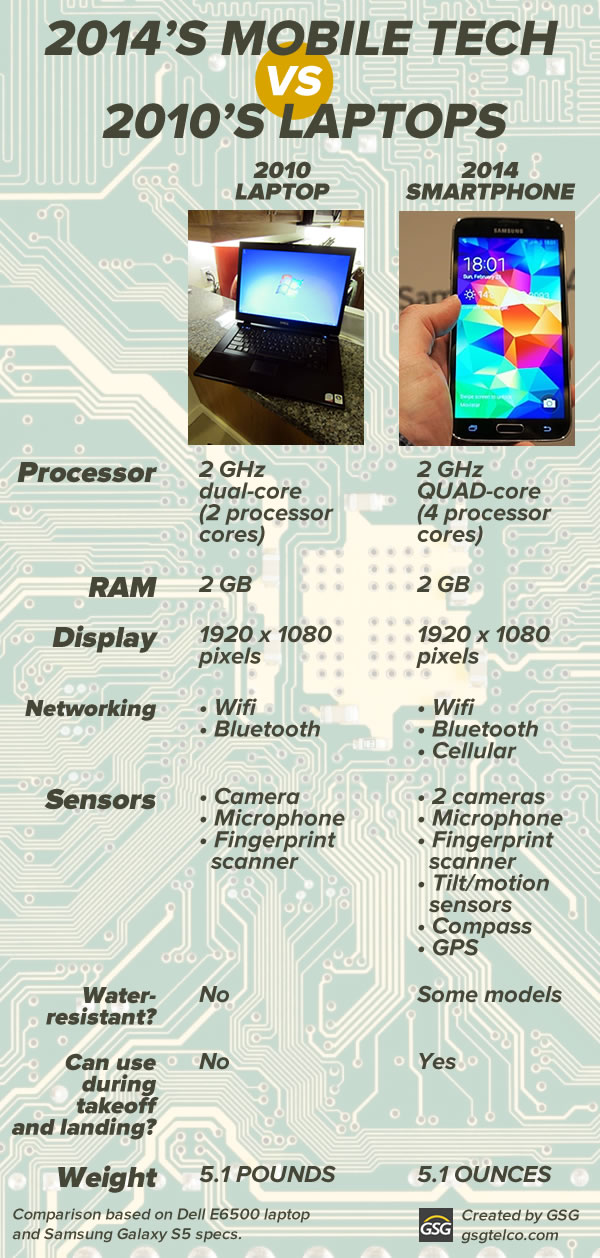

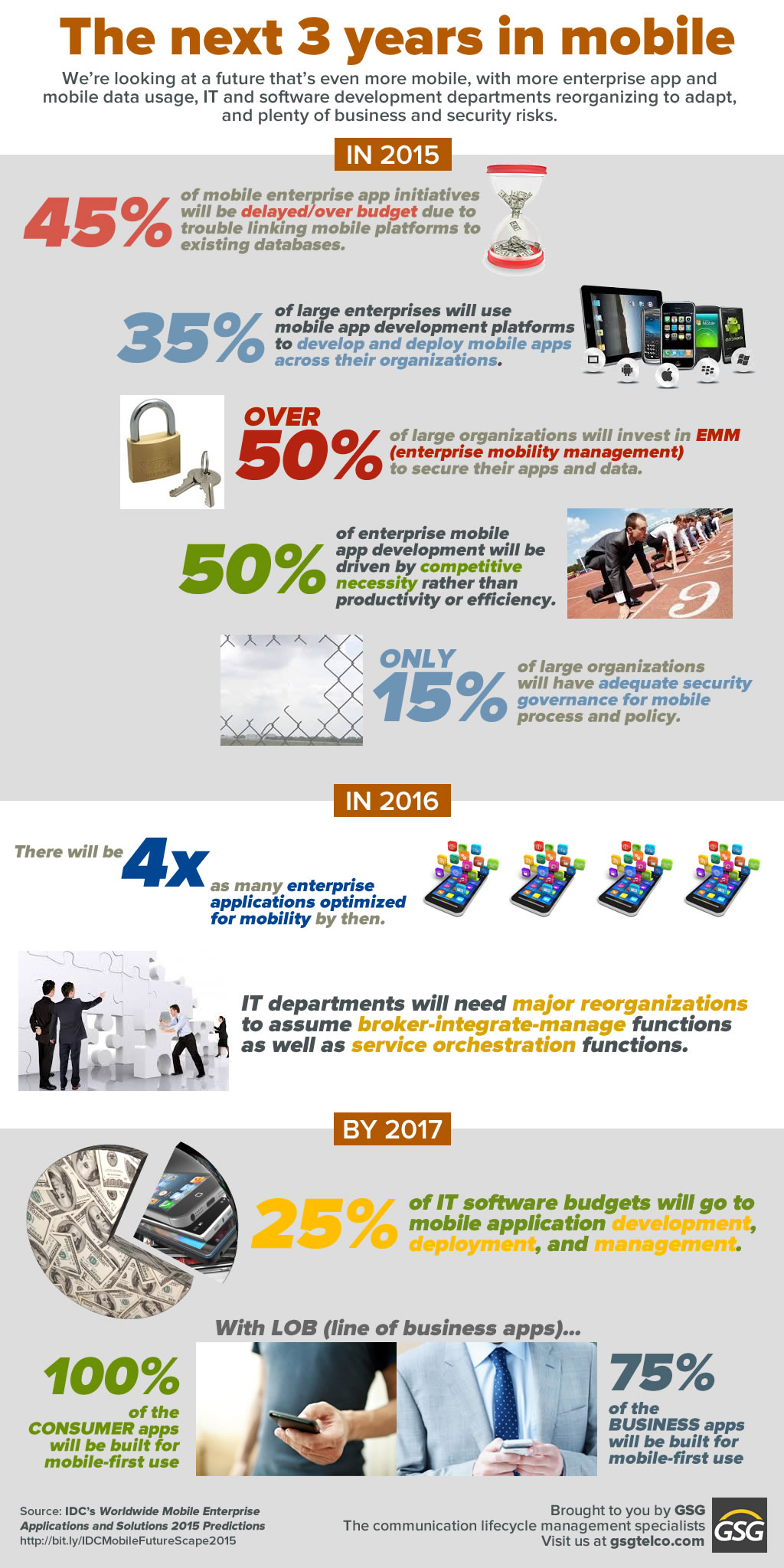

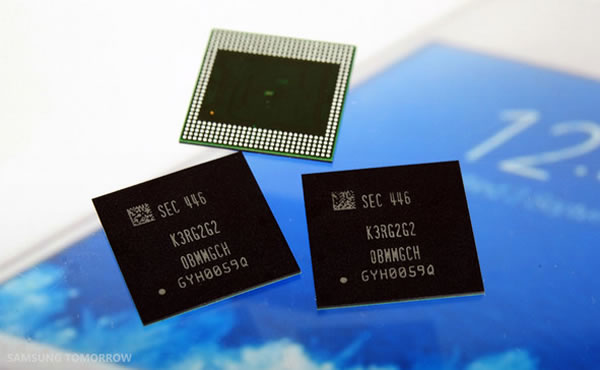

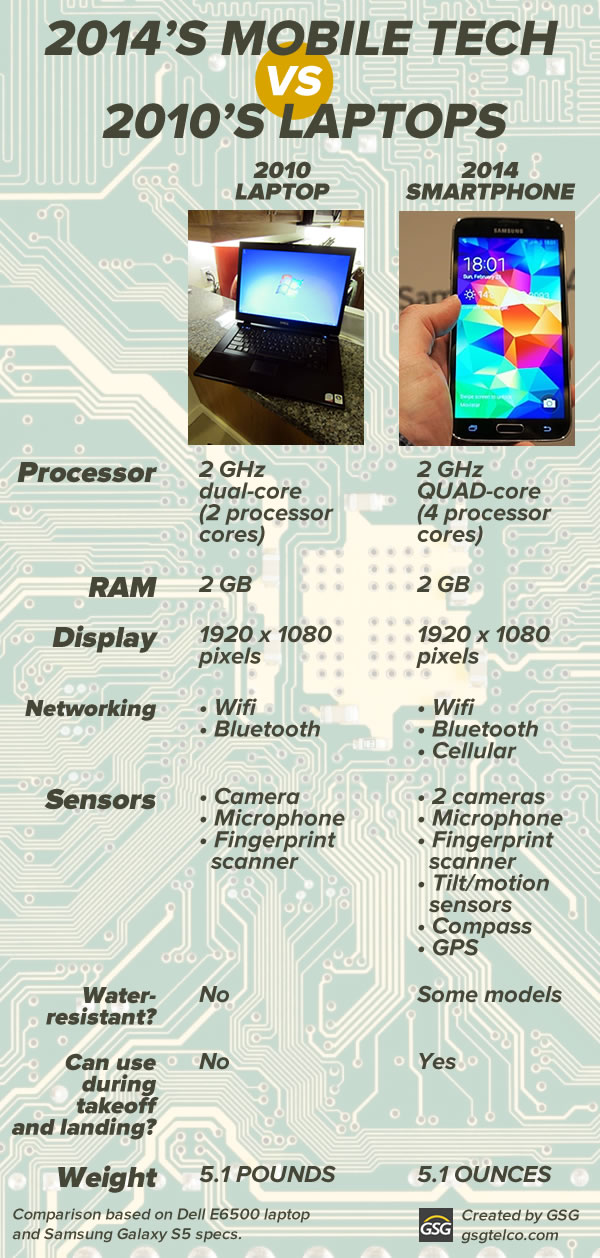

Samsung starts mass production of chips that will reduce the gap between smartphone power and laptop power

If you take a look at Best Buy’s selection of laptops, you’ll see they currently start at 4GB RAM, which these days is considered to be the minimum for running today’s operating systems and applications. Today’s smartphones currently have at most 2GB of RAM (and iOS devices are getting a lot of bang out of a mere 1GB). This is expected to change in the coming year as Samsung ramps up their production of their latest RAM chips, which have twice the capacity of their current best chips, and consume only 60% of the power.

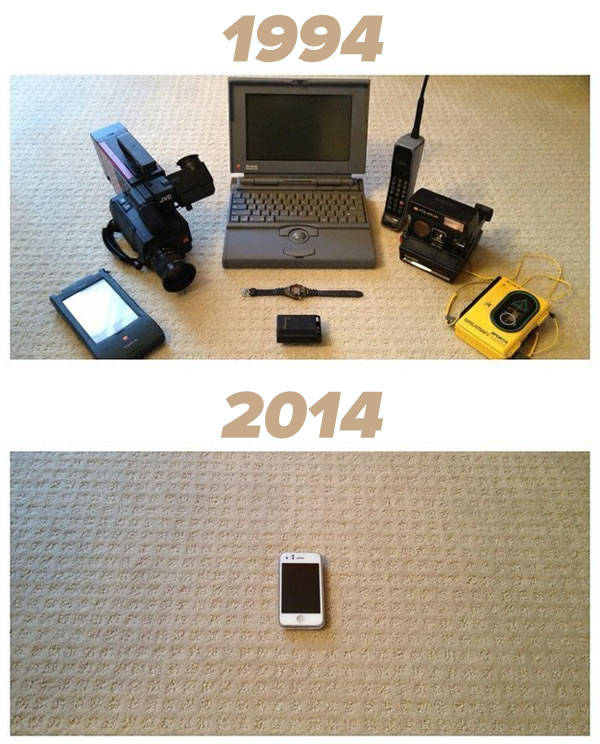

The gap between mobile devices and laptops has been closing for some time. If you’d like to know more, check out our infographic, which you can also download from Pinterest:

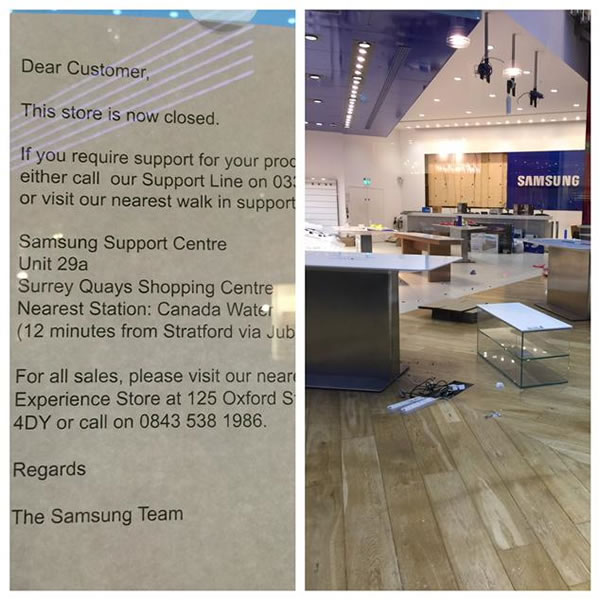

A blue Christmas for Samsung’s flagship store in London

Photo by Najeeb Khan. Click to see the source.

London’s flagship Samsung Experience store, located in the Westfield Stratford City shopping center, has closed its doors permanently. As one of the two large Samsung shops in London, it was meant to be the go-to place to try out — and hopefully, buy — Samsung devices. However, with Samsung dropping out of the laptop business in Europe, their losing mobile sales to nimbler, cheaper Android competitors, and given the high price of London real estate, they had to close shop.

There are still a number of smaller Samsung stores in the UK, and so far, the company still has plans to open 60 new retail locations in Europe. We’ll have to see what happens with them in the new year.

iPhone 6 demand is strong, and supplies are surging just in time for the holidays

Gene Munster, an analyst with investment bank/asset management company Piper Jaffray reports that there’s good news for Apple investors and people who want an iPhone 6: demand for Apple’s newest, largest phones is strong, and Apple’s supply chain seems able to meet that demand. Here’s what he has to say about the demand:

We conducted a survey of 1,004 US consumers. Of those looking to purchase a smartphone in the next three months, 50% said they plan on purchasing an iPhone vs. 47% in September, following the iPhone 6 announcement. By comparison, demand for the iPhone decreased from 50% in Sep-13 to 44% in Dec-13 following the iPhone 5S launch. Overall we believe this shows that consumers are extremely interested in the larger screen iPhone 6, a testament to the strength of the current upgrade cycle.

And here’s his take on the supply:

While supply of the iPhone 6/6 Plus has been constrained since launch, our store checks suggest that supply is improving. In our checks of 80 Apple retail stores at the end of last week, we noted that 77.6% of stores had iPhone 6 units in stock vs. 56.1% of stores in the prior week.

Zacks Investment Research is also bullish on Apple, with analyst Eric Dutram calling the company the “Bull of the Day”, based on their 2015 prospects, which will include the release of the Apple Watch.