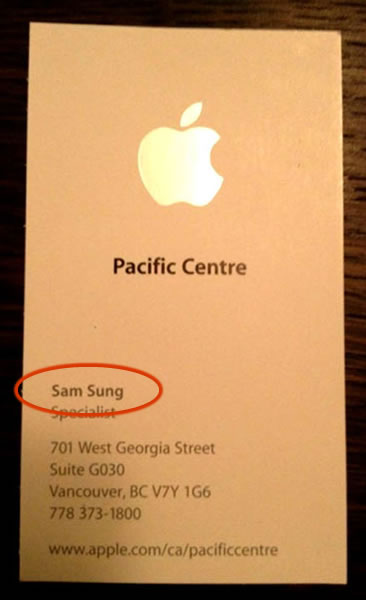

Oh please, let this be real and not just an elaborate but funny prank.

Found via Make Use Of.

I’m sure he gets beaten up by the iPhone team every day.

Oh please, let this be real and not just an elaborate but funny prank.

Found via Make Use Of.

I’m sure he gets beaten up by the iPhone team every day.

As I write this, StatCounter is reporting that my recent post on giving the FizzBuzz test to developer job candidates has received over 21,000 pageviews. Without any prompting from me, my friend Reg “Raganwald” Braithwaite (we both live in Toronto and see each other from time to time) linked to it from both r/programming and Hacker News, and the discussion that first started five years ago with Imran Ghory’s blog post began anew. I thought I’d respond to questions posted in both the comments and forums here, as well as explain a few things.

We’re a small consultancy creating two different applications:

We’re currently paying the bills and getting in some market research by doing mobile strategy assessments for enterprises and organizations. We’ve also been approached about developing mobile “dashboard” applications that provide a high-level view of supply chains.

The positions we were looking to fill were:

A company like ours, at this particular stage of its evolution, often requires its people to not only perform their jobs really, really well, but to also take on a number of other roles as the situation dictates. Circumstances have already required us to — I hate to use the word, but it’s appropriate — pivot. We’re dealing with limited resources, long enterprise sales cycles, the moving-target nature of mobile development and Murphy’s Law. When it comes to hiring, we can’t afford not to be picky.

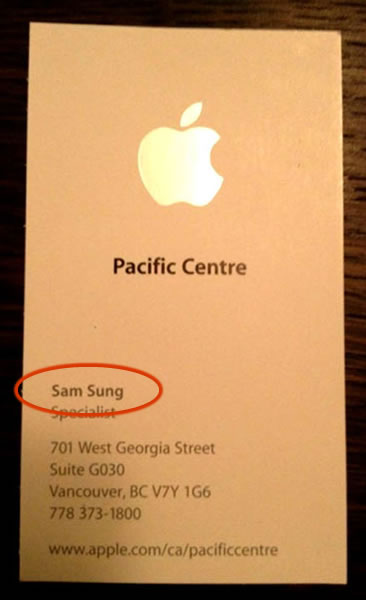

That’s me: High Expectations Asian CTO.

In the comments, Vasi wrote:

I’m curious what “failures” look like. Is it complete inability to get anything done at all? Or relatively small mistakes, like ending at 99 instead of 100?

One candidate took longer than 10 minutes while working on FizzBuzz. Since we had only an hour for each interview and a number of candidates to go through, we I had to set that time limit. The candidate had decades of experience, was the one who asked “Do you think I should use a loop?”, and handed this in when time was up:

// Written in C

for (i = 1; i <= 100; i++) {

// A whole lotta stuff scratched out

}

I’m sorry; this is just plain unacceptable.

The most common mistake followed this pattern:

// Written in PHP if ($i % 3 == 0) echo "Fizz<br />"; if ($i % 5 == 0) echo "Buzz<br />"; if ($i % 15 == 0) echo "FizzBuzz<br />"; echo ($i . "<br />");

I consider knowing when to use a series of if statements and when to use if–else if–else to be pretty fundamental, especially for a problem as simple as FizzBuzz.

I was willing to let the classic “using the assignment operator when you meant to use the equality operator” mistake slide:

if (i % 3 = 0)

I was less willing to let this mistake go unremarked:

// Written in PHP

if ($i % 3) {

echo "Fizz<br />";

} elseif ($i % 5) {

echo "Buzz<br />";

} elseif ($i % 15) {

echo "FizzBuzz<br />";

} else {

echo ($i . "<br />");

}

Even if the mistakes in the conditionals were fixed, there would still be a problem with the code. Please tell me you can spot it.

Max Howell was the first of a number of commenters to write:

Is the modulus operator domain knowledge? I smirk at the concept. But if an interview asked me to do some bit operations with ~|& etc. it would take me longer than five minutes, and if I had to use ^ (XOR) I’d probably be screwed.

Good question. Our company makes mobile apps for business, and the candidates were made aware of that. I consider the modulus (%) operator to be one of those things that you need to know about in programming for business, because there are many cyclical things that you deal with: days of the week, displaying tables with lines in alternating colours and so on.

On the other hand, using XOR — I’m presuming that Max is referring to the handy-dandy trick for swapping the values in two variables without the use of a temporary variable — isn’t as applicable to the sort of apps we’re writing. However, if we were in the business of writing games or other sorts of apps where bit-twiddling is important, then knowing how to use XOR and its ilk would be important.

Timothy asked what would’ve happened if someone had submitted this solution:

// Written in C# Console.WriteLine(1); Console.WriteLine(2); Console.WriteLine(“Fizz”); Console.WriteLine(4); Console.WriteLine(“Buzz”); … Console.WriteLine(14) Console.WriteLine(“FizzBuzz”) Console.WriteLine(16) …

He pointed out that not only does this solution works, it uses less CPU power than a solution involving a loop and branching.

I replied that if it were apparent to me that a candidate submitted such a solution and made it clear to me that it was submitted in the spirit of smartassery, I’d give the canddiate points for chutzpah. I’d also give the candidate points for arguing that it’s less CPU-intensive; after all, we are a mobile app company, and battery life is one of those things that our developers have to consider.

Of course, I’d then have to follow up with “Could you give me another implementation, please? Perhaps one using looping and branching?”

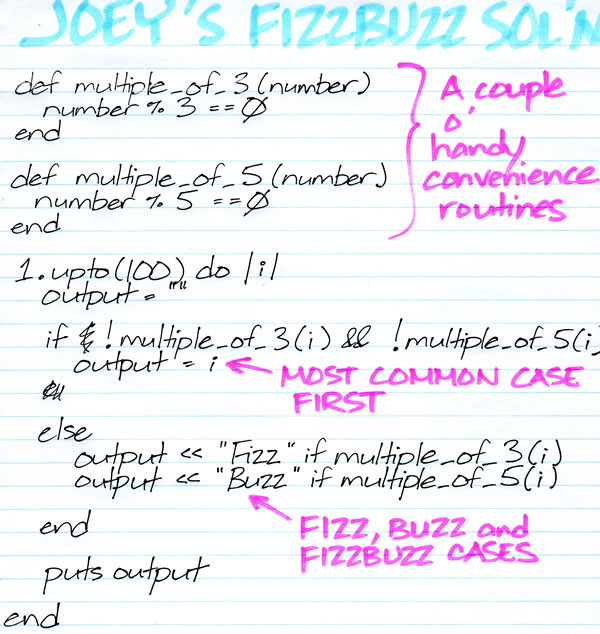

multiple_of_3 and multiple_of_5?For these reasons:

multiple_of_3 than (i % 3 == 0).fizz? and buzz? instead.Mouad suggested that candidates might believe that the test is too simple and suspect that there’s some kind of trick. I assured them that it was not a trick question and should be taken at face value.

E.Z. Hart asked:

Out of curiosity, how many is ‘some programmers’? I’m just wondering what the sample size is here.

We’ve promised to certain parties to keep this number vague. The best I can do is say that the total number of candidates could fit in a standard city bus.

Peter wrote:

Giving programming tests in interviews is bullying in the most pathetic passive-aggressive way possible. The programming field is full of dbags and this type of interview test is an example of what happens when said dbags are given the chore of interviewing.

D-bag? A comment as stand-out as this calls for an equally stand-out reply:

But seriously: it would’ve been a d-bag move had the purpose of the test been to reinforce my ego by trampling on candidates, to trip them up by requiring some esoteric knowledge or for some other equally malicious purpose. That’s why I used FizzBuzz; it tests basic aptitude and it’s over fairly quickly. This job is going to be stressful, and if FizzBuzz is giving you palpitations, you’re not going to like the real thing.

A far more difficult test was the one given to me when I flew down to Palo Alto this summer and interviewed at Pebble to be their developer evangelist (I didn’t get the job, but then again, no one else did). They interviewed me over two days, and on day one, they tested me by telling me to build an app — any app — for their previous smartwatch, the inPulse, just to prove that I could code. There was no spec, not much in the way of documentation, but looking at some example code and the comments in the API header files, I was able to put together a working “Magic 8-Ball” app in less than an hour. (I later turned that app into this tutorial.) I considered the test tough, but fair, because their project is a high-stakes one.

Our company doesn’t face the same level of risk as Pebble, but there’s risk involved. We’re bootstrapping the company, which means that until we get customers or funding, everyone’s salary is coming out of our pockets. I feel completely justified in taking fair measures that ensure that we’re not wasting his money.

Yes, we asked them to show us projects that they worked on and saw samples of their code. Not all candidates were able to provide samples; some didn’t have code from their previous work, some of their projects were internal web apps that couldn’t be set up on a personal laptop, and some didn’t have side projects they could show me.

I also had each candidate do a quick code review with me of code written by an earlier developer for our applications. I explained what that code was supposed to do and showed them the running application in action. We looked over the code and I asked the candidates to tell me what they thought of it. While the code worked, it was a big ball of mud with plenty of room for improvement. A number of the candidates said “That looks like something I would write! It’s good!”, while others came up with a number of good suggestions for improving it.

They helped bring in a good number of candidates, and they also helped pick out people who would be a good fit for the company. They spent a fair bit of time talking to us to get a feel for the company culture and how we worked. We explained to them that we needed people who were self-starters and comfortable with the sort of risks and uncertainty that would come with the territory. We told them not to worry too much about the technical aspects of the candidate, as we’d be handling that.

The candidates who came in via the recruiter were interviewed by them first, after which those deemed to be a good match for us were then sent our way.

I kept that in mind. That’s why we didn’t rely solely on FizzBuzz. Remember: I’ve been doing either technical evangelism or developer relations for the past ten years. I think I know a think or two about “reading” developers; in fact, at Microsoft, I took some pretty extensive training on that topic.

These ads for Asus’ suspiciously familiar-looking ultrabooks are plastered all over Toronto’s Bloor/Yonge subway station:

For all the aping of Apple’s MacBook/AirBook designs, it still doesn’t play the “See? We’re just like Apple!” card as hard as the Dell ad recently featured in Daring Fireball:

I recently interviewed some programmers for a couple of available positions at CTS, the startup crazy enough to take me as its CTO. The interviews started with me giving the candidate a quick overview of the company and the software that we’re hiring people to implement, after which it would be the candidate’s turn to tell his or her story. With the introductions out of the way — usually at the ten- or fifteen-minute mark of the hour-long session, I ran each candidate through the now-infamous “FizzBuzz” programming test:

Write a program that prints out the numbers from 1 through 100, but…

- For numbers that are multiples of 3, print “Fizz” instead of the number.

- For numbers that are multiples of 5, print “Buzz” instead of the number

- For numbers that are multiples of both 3 and 5, print “FizzBuzz” instead of the number.

That’s it!

This was the “sorting hat”: the interview took different tacks depending on whether the candidate could or couldn’t pass this test.

I asked each candidate to do the exercise in the programming language of their choice, with pen and paper rather than on a computer. By requiring them to use pen and paper rather than letting them use a computer, I prevented them from simply Googling a solution. It would also force them to actually think about the solution rather than simply go through the “type in some code / run it and see what happens / type in some more code” cycle. In exchange for taking away the ability for candidates to verify their code, I would be a little more forgiving than the compiler or interpreter, letting missing semicolons or similarly small errors slide.

The candidates sat at my desk and wrote out their code while I kept an eye on the time, with the intention of invoking the Mercy Rule at the ten-minute mark. They were free to ask any questions during the session; the most common was “Is there some sort of trick in the wording of the assignment?” (there isn’t), and the most unusual was “Do you think I should use a loop?”, which nearly made me end the interview right then and there. Had any of them asked to see what some sample output would look like, I would have shown them a text file containing the first 35 lines of output from a working FizzBuzz program.

The candidates sat at my desk and wrote out their code while I kept an eye on the time, with the intention of invoking the Mercy Rule at the ten-minute mark. They were free to ask any questions during the session; the most common was “Is there some sort of trick in the wording of the assignment?” (there isn’t), and the most unusual was “Do you think I should use a loop?”, which nearly made me end the interview right then and there. Had any of them asked to see what some sample output would look like, I would have shown them a text file containing the first 35 lines of output from a working FizzBuzz program.

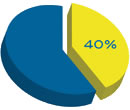

The interviews concluded last week, after which we tallied the results: 40% of the candidates passed the FizzBuzz test. Worse still, I had to invoke the Mercy Rule for one candidate who hit the ten-minute mark without a solution.

I was surprised to find that only one of the candidates had heard of FizzBuzz. I was under the impression that that it had worked its way into the developer world’s collective consciousness since Imran Ghory wrote about the test back in January 2007:

On occasion you meet a developer who seems like a solid programmer. They know their theory, they know their language. They can have a reasonable conversation about programming. But once it comes down to actually producing code they just don’t seem to be able to do it well.

You would probably think they’re a good developer if you’ld never seen them code. This is why you have to ask people to write code for you if you really want to see how good they are. It doesn’t matter if their CV looks great or they talk a great talk. If they can’t write code well you probably don’t want them on your team.

After a fair bit of trial and error I’ve come to discover that people who struggle to code don’t just struggle on big problems, or even smallish problems (i.e. write a implementation of a linked list). They struggle with tiny problems.

So I set out to develop questions that can identify this kind of developer and came up with a class of questions I call “FizzBuzz Questions” named after a game children often play (or are made to play) in schools in the UK.

Ghory’s post caught the attention of one of the bright lights of the Ruby and Hacker News community, Reg “Raganwald” Braithwaite. Reg wrote an article titled Don’t Overthink FizzBuzz, which in turn was read by 800-pound gorilla of tech blogging, Jeff “Coding Horror” Atwood. It prompted Atwood to ask why many people who call themselves programmers can’t program. From there, FizzBuzz took on a life of its own — just do a search on the term “FizzBuzz”; there are now lots of blog entries on the topic (including this one now).

In Dave Fayram’s recent article on FizzBuzz (where he took it to strange new heights, using monoids), he observed that FizzBuzz incorporates elements that programs typically perform:

I can’t go fairly judge other programmers with FizzBuzz without going through the test myself. I implemented it in Ruby, my go-to language for hammering out quick solutions, and in the spirit of fairness to those I interviewed, I did it with pen and paper on the first day of the interviews (and confirmed it by entering and running it):

I consider myself a half-decent programmer, and I’m pleased that I could bang out this solution on paper in five minutes. My favourite candidates from our interviews also wrote up their solutions in about the same time.

Okay, the picture above shows a 33% pass rate. Close enough.

How is it that only 40% of the candidates could write FizzBuzz? Consider that:

A whopping sixty percent of the candidates made it past these “filters” and still failed FizzBuzz, and I’m not sure how. I have some guesses:

If you’re interviewing prospective developers, you may want to hit them with the FizzBuzz test and make them do it on paper or on a whiteboard. The test may be “old news” — Imran wrote about it at the start of 2007; that’s twenty internet years ago! — but apparently, it still works for sorting out people who just can’t code.

Be sure to read the follow-up article, Further Into FizzBuzz!

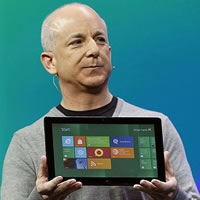

Goodbye, Mr. Sinofsky, and thank you for teaching me two of the most valuable lessons in office politics during my tenure at The Empire:

To be fair, Sinofsky is that combination of “smart” and “gets things done”. In his heartfelt “farewell” article, Dare Obasanjo writes that he took some products in need of fixing up and love — Windows Vista, Surface-the-big-ass-table, “a mish mash of confusing consumer synchronization products” — and turned them around into dramatically improved versions: Windows 7 and 8, Surface-the-tablet and SkyDrive.

To be fair, Sinofsky is that combination of “smart” and “gets things done”. In his heartfelt “farewell” article, Dare Obasanjo writes that he took some products in need of fixing up and love — Windows Vista, Surface-the-big-ass-table, “a mish mash of confusing consumer synchronization products” — and turned them around into dramatically improved versions: Windows 7 and 8, Surface-the-tablet and SkyDrive.

Other takes:

Shareholders have already braced themselves for a drop in value — not the $60 or $70 that Apple’s has dropped to the low, low, low price of $540 a share after Forstall’s and Browett’s departure announcements — but by about a buck to $27-and-change at the time of this writing.

At their Toronto meetup, TechCrunch conducted a number of video interviews with Toronto area-based startups, two of which were Shifthub and Maluuba, which I’m showing below.

Shifthub aims to solve the problems of coordinating the schedules of employees who work in shifts. If you’ve ever worked in retail or at a restaurant or bar, you know how easily bunged up employee scheduling can get, especially when you’ve got factors like high turnover, personal emergencies and people trading shifts. Now that a lot of people’s tips go towards the purchase of a smartphone, a system like Shifthub, which handles the scheduling of staff and lets staff work out changes to their schedules in a way that ensures those changes don’t get lost in the shuffile, makes plenty of sense. Shifthub was founded by my old Tucows coworker James Woods (not the actor/Peter Griffin stalker) and Jeremy Potvin, who chatted with TechCrunch‘s East Coast Editor (and my homeboy) John Biggs in the video below:

Shifthub aims to solve the problems of coordinating the schedules of employees who work in shifts. If you’ve ever worked in retail or at a restaurant or bar, you know how easily bunged up employee scheduling can get, especially when you’ve got factors like high turnover, personal emergencies and people trading shifts. Now that a lot of people’s tips go towards the purchase of a smartphone, a system like Shifthub, which handles the scheduling of staff and lets staff work out changes to their schedules in a way that ensures those changes don’t get lost in the shuffile, makes plenty of sense. Shifthub was founded by my old Tucows coworker James Woods (not the actor/Peter Griffin stalker) and Jeremy Potvin, who chatted with TechCrunch‘s East Coast Editor (and my homeboy) John Biggs in the video below:

The guys at Maluuba describe it as a “do engine” that understands what you say in order to help you get things done. It takes your natural conversations and converts them into queries that are applied to a set of third-party services and takes action on your behalf. Asking Maluuba about when the next showing of Skyfall takes place will show you movie listings for your area and give you the option of setting a reminder or marking a date in your calendar. Wolfram Alpha provides it with general knowledge, while other information is provided by Wikipedia, Yelp, Rotten Tomatoes, Weather Underground, Eventful and more. In the video below, TechCrunch’s Jordan Crook talks with Maluuba’s Tareq and Eric:

The guys at Maluuba describe it as a “do engine” that understands what you say in order to help you get things done. It takes your natural conversations and converts them into queries that are applied to a set of third-party services and takes action on your behalf. Asking Maluuba about when the next showing of Skyfall takes place will show you movie listings for your area and give you the option of setting a reminder or marking a date in your calendar. Wolfram Alpha provides it with general knowledge, while other information is provided by Wikipedia, Yelp, Rotten Tomatoes, Weather Underground, Eventful and more. In the video below, TechCrunch’s Jordan Crook talks with Maluuba’s Tareq and Eric:

Last night, TechCrunch came to town and invited 1,000 people to come and mingle at the Steam Whistle Brewery. Anitra and I attended the event, which was packed solid. Even with 1,000 free tickets available, there were still a large number of people waitlisted.

The photo above shows the party floor as things were winding down. At the start of the party, the place was packed solid, with local tech startup people watching demos put on by startups who managed to pull together the $1,500 sponsor fee, catching up with each other and trying to meet new co-founders, collaborators, funders and employees.

A good number of the Usual Suspects were there, including Rannie “Photojunkie” Turingan and Rob Tyrie, pictured above. Also present were some of my former colleagues at Shopify, including Blair Beckwith, Brian Alkerton and Mark Hayes, Shoplocket co-founders Katherine Hague and Andrew Louis, Anna Starasts from Grossman Dorland, James Woods from Shifthub (I worked with him at Tucows, along with Greg Frank, who was also there), Julie Tyios (who I cracked up with my Ford Canada interview), Vahid Jozi (whom I met while in Ottawa), Austin Ziegler, Jon from Venio, Rohan “Silver Fox” Jayasekara, John Gauthier and Jean-Luc David, to name a few. Special out-of-town mention has to go to Greg “Gregarious” Narain.

John Biggs and Yours Truly at TechCrunch Toronto.

My moment of the evening: when John Biggs, TechCrunch’s East Coast Editor saw me and asked “Is that the Accordion Guy?” It turns out that’s he’s been a reader of The Adventures of Accordion Guy in the 21st Century for some time! I’ve been following his stuff since he was Editor-in-Chief at Gizmodo, so the recognition made me feel like a rock star — a very nice birthday present!

Events like this are good for our local startup ecosystem. The chance meetings and exchange of ideas at shindigs like this have led to all sorts of things: friendships, collaborations, partnerships, employment and even getting some funding, but most importantly, they lend that sense of cohesiveness necessary to creating an environment where little businesses built on big ideas can thrive. My thanks to the folks at TechCrunch, the sponsors and all who came for making this event a fun and productive one!

You can read the TechCrunch summary of the event here.

This article also appears in The Adventures of Accordion Guy in the 21st Century.