Welcome to another article in the Counting Down to Seven series and the first article in the Exploring XNA series — it’s like the chocolate and peanut butter of mobile development!

If you haven’t read Windows Phone team member Charlie Kindel’s latest blog entry yet, do so now. In explaining what’s different in Windows Phone 7, he also lists some technologies that form it basis:

- .NET

- Silverlight

- XNA

- Web 2.0 standards

- Microsoft’s developer tools

That’s right: along with Silverlight, one of the core elements of Windows Phone 7 is XNA, the toolset that makes it quite easy to build games for the PC, Xbox 360 and Zune. Kudos to those of you who ratiocinated that Silverlight and XNA would figure into Windows Phone: both are proven user interface technologies that have also shown that they’re capable of living on different platforms.

I’ll cover each of the core elements of Windows Phone 7 in the fullness of time, but for now, why don’t we start with what I consider to be the really fun one – XNA?

(It’s not only fun – it’s the gateway to customers: according to eMarketer, the number of people who play games on their phone has more than doubled in the past couple of years, from 155 million in 2007 to a predicted 340 million by the end of 2010.)

XNA: A Quick Overview

In the venerable geek tradition of using recursive acronyms to name things, XNA is short for “XNA’s Not Acronymed”. In the Microsoft-y tradition of using one name to represent a smorgasbord of things, XNA is a framework, toolset and runtime that makes it easier to build and deploy games.

XNA provides a great skeleton for building 2-D and 3-D games with a set of game-centric class libraries and a straightforward programming model. Its design frees you from a lot of the “yak shaving” and related drudgery involved in game development, letting you spend more time on programming the gameplay instead. Its “simple but not stupid” quality recently allowed me to walk a workshop of Humber College students from an initial “let’s draw a static sprite on the screen” project to a pretty decent “run around the game field, dodging the flying spinning blades” game, complete with animated sprites, sound effects and soundtrack and scoring, all in about three hours. Better still, we had fun doing it.

Required and Optional Tools for XNA Development

Here’s what you need (and some nice-to-haves) to get started with XNA development:

Required

- Windows 7, Vista or XP, with the latest service packs installed.

- Visual Studio 2008, which costs money, or Visual C# 2008 Express Edition, which is free-as-in-beer. Don’t let its being free throw you off; it’s a complete IDE and more than enough for developing games. As of this writing, the 2010 editions of Visual Studio, which have not yet hit the “Release to Manufacturing” stage, don’t support XNA game development yet.

- XNA Game Studio 3.1. This is a set of Visual Studio add-ons and tools for developing games for Windows, Xbox 360 and Zune using XNA. This is also free-as-in-beer.

Optional

- A PC-compatible Xbox 360 controller. This can be:

- A wired Xbox 360 controller, which plugs directly into your PC’s USB ports.

- A wireless Xbox 360 controller with the Xbox 360 Wireless Gaming Receiver plugged into your PC’s USB port.

- A wireless Xbox 360 controller for Windows.

- An Xbox 360, if you want to build console games, for which you’ll need a Premium membership with XNA Creators Club Online (CDN$119 per year, or CDN$59.00 for 4 months).

- A Zune, if you want to build Zune games. You can deploy to the Zune for free.

Platformer: XNA’s “Right Out of the Box” Game

If you’re the sort who wants to play a game before doing some game development, you’re in luck. XNA provides Platformer, a fully-functional “platform jumper” game as one of its project templates. You can simply treat is as a game, but that would be a waste – its true value is that in its source code are a lot of lessons in building 2-D games with XNA. I’m going to show you how to build a Platformer project.

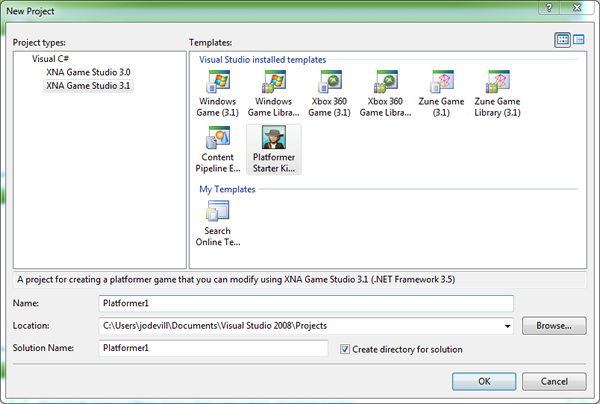

(In the screenshots below, I opted to use free Visual C# 2008 Express. If you have one of the full version of Visual Studio, the experience will be similar.)

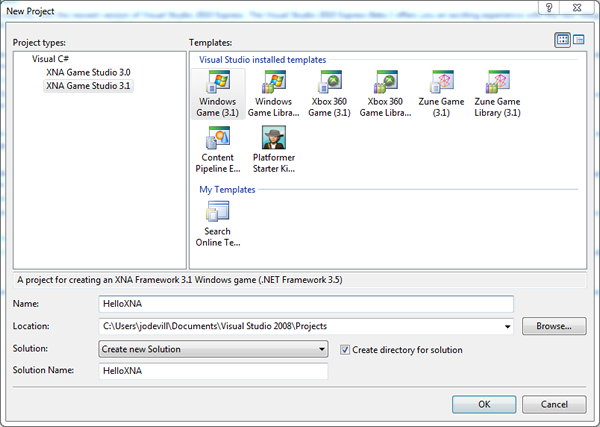

Start up Visual C# 2008 Express or Visual Studio. From the File menu, select New Project… You should see a dialog box like the one shown below appear.

In the Project types: list on the left-hand side of the dialog box, select Visual C# and the select XNA Game Studio 3.1 from its sub-menu. In the Templates list on the right-hand side of the dialog box, you should see a number of game application templates. Select Platformer Starter Kit. Fell free to the edit the contents of the Name: textbox if you want to give your project a different from the default and click the OK button.

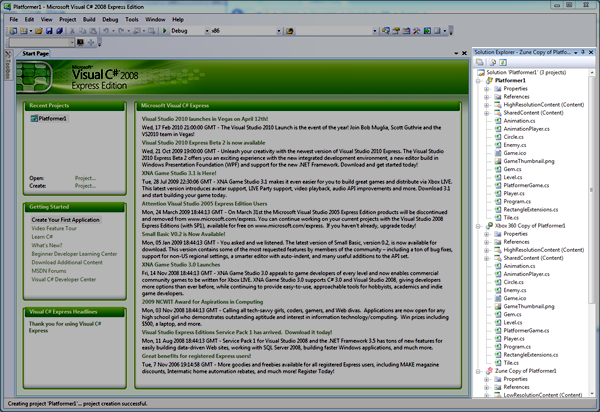

Visual Studio will generate a new project. You’ll know because the Solution Explorer pane will be filled with projects and their files:

Press F5 to run the game. In moments, you’ll be greeted by the screen below:

Platformer looks like an homage to both platform games as well as Raiders of the Lost Ark. You’re represented by an Indiana Jones-esque sprite and must reach the “Exit” sign before time runs out. You have the option of collecting gems to increase your score.

You move to the next level if your reach the exit sign before time runs out:

Here’s level two, which features more platforms, more gems and a shambling mummy who can kill you with a touch:

Here’s level three, which is filled with platforms that you can jump through:

Make sure you check out the code for Platformer. Reading it is a great way to learn XNA game development techniques and tricks.

Hello, XNA!

Once you’re done playing Platformer, you might want to try your hand at XNA development. I’m not going to show you how to write anything resembling a game in this article (I’ll do that over the next few articles in this series), but I thought I’d quickly show you how to get the world’s simplest XNA application – in the best “Hello, World!” tradition – up and running.

Just as you did with Platformer, click on the File menu, select New Project… This time, when the New Project dialog box appears, select Windows Game (3.1), give the project a name in the Name text box (I chose HelloXNA) and click OK:

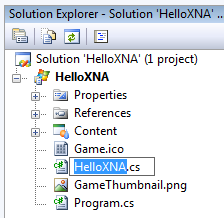

Visual Studio (or Visual C# Express) will then generate your game project.

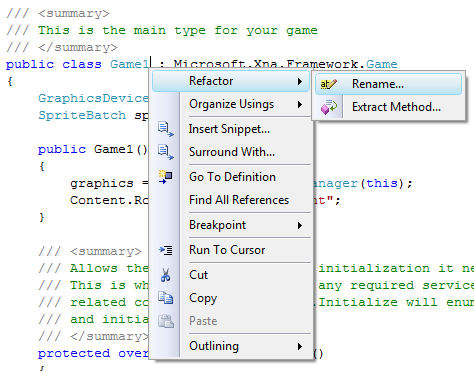

A newly-created XNA game project has all its code living in a single class, which is given the name Game1, which in turn is stored in the file Game1.cs. I want to rename that class to HelloXNA. That’s easily done by moving the cursor over Game1 at the start of the class declaration, right-clicking on it, selecting Refactor from the menu that appears, and then Rename… from the submenu:

I could use good ol’ search-and-replace, but it blindly taking the search term and changing it into the replacement term, no matter where it is. Refactor –> Rename… is smarter; it does a true renaming of the identifier without mangling other identifiers that happen to contain the search term. It also allows you to specify whether you want to do the renaming in comments and string literals, which old-school search-and-replace doesn’t do.

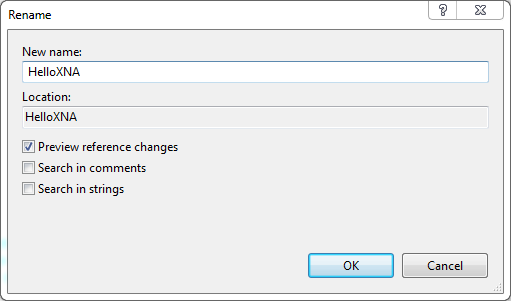

When the Rename dialog box appears, enter the new name for the Game1 class, HelloXNA, into the New name: text box. Make sure that the Preview reference changes checkbox is checked before clicking OK:

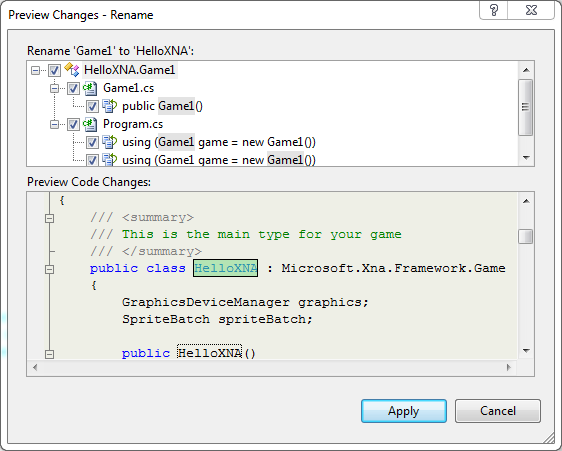

If you checked the Preview reference changes checkbox in the previous dialog box, you’ll see a preview of the changes that will result if you apply Refactor –> Rename…. Click Apply to finalize the renaming:

You’ll see that the Game1 class and any references to it in the code have been changed to HelloXNA. For consistency’s sake, we’ll rename the Game1.cs file in which the class formerly known as Game1 to HelloXNA.cs in the Solution Explorer:

By default, a brand-new XNA game project without any code added to it does a very simple thing: it draws a blank screen with a cornflower blue background. If you hit F5 to run the application right now, you’ll see this:

Now “all you have to do” is write some game code! I’ll walk you through that process over the next few articles in this series.

Next Steps

You could wait for the next article in this series, but if you’re rarin’ to learn how to develop games with XNA, let me recommend Learning XNA 3.0, written by Aaron Reed and published by O’Reilly. It has a 4.5-star rating at Amazon.com, which it’s earned – it’s a great introduction to XNA development. The first half of the book is devoted to 2-D game development, starting with drawing a sprite on the screen and finishing with a pretty complete game. The second half of the book adds the third dimension and works towards building a 3-D game.

You should also get a look at XNA Creators Club, the online community for XNA developers. It features:

- Links to all the downloads you need to get started developing games with XNA

- Starter kinds for various game genres – you get Platformer with XNA; you can download starter kits for other game genres, including:

- Marblets: a marble colour-matching puzzle game.

- Spacewar: the classic “spaceship vs. spaceship” game that comes in two flavours – retro and evolved.

- Role-Playing Game: A tile-based RPG engine with support for character classes, multiple party members, items and quests.

- Racing Game: A 3-D auto racing game featuring advanced graphics, audio and input processing, where you race against the ghost car for the best time.

- Ship Game: 3-D spaceship combat in a tunnel system with advanced lighting and textures, a full GPU particle system and an advanced physics engine.

- Net Rumble: A 2-D shooter showcasing XNA’s new multiplayer features in an arena with asteroids, power-ups and up to 16 players.

- Forums to discuss ideas and ask questions with your fellow XNA game developers

- A catalog of games created by members of the XNA game developer community. You can try out their games, submit games and vote for games to be included in the Xbox Indie Games catalog, whose games can be purchased through Xbox Live.

If you want to be a rock star on Windows Phone 7, you’re going to want to sharpen your XNA chops. Get a head start and take it out for a spin!

This article also appears in Canadian Developer Connection.