You may remember this tweet from a little less than four months ago:

The tweeter of that viral post and sleeper in the photo is Esther Crawford, Director of Product Management at Twitter — or at least she was. This weekend, she and at least 50 other employees were laid off.

She was recently the subject of an article in the Financial Times on January 24th (barely over a month ago) titled The rise of Esther Crawford in Elon Musk’s ‘hardcore’ Twitter. It tells the story of how she managed to become one of the few pre-Musk employees to parley their way into becoming one of “Space Karen’s” trusted lieutenants and in charge of several initiatives to make the company profitable, including Twitter Blue.

Her “sleeping bag” tweet raised a lot of eyebrows, including this short, yet spot-on response from Grady Booch, one of the patron saints of software development (and object-oriented programming in particular):

Crawford followed up with a multiple-tweet response:

[1] Since some people are losing their minds I’ll explain: doing hard things requires sacrifice (time, energy, etc). I have teammates around the world who are putting in the effort to bring something new to life so it’s important to me to show up for them & keep the team unblocked.

[2] I work with amazingly talented & ambitious people here at Twitter and this is not a normal moment in time. We are less than 1wk into a massive business & cultural transition. People are giving it their all across all functions: product, design, eng, legal, finance, marketing, etc

[3] We are #OneTeam and we use the hashtag #LoveWhereYouWork to show it, which is why I retweeted with #SleepWhereYouWork — a cheeky nod to fellow Tweeps. We’ve been in the midst of a crazy public acquisition for months but we keep going & I’m so proud of our strength & resilience.

[4] I love my family and I’m grateful they understand that there are times where I need to go into overdrive to grind and push in order to deliver. Building new things at Twitter’s scale is very hard to do. I’m lucky to be doing this work alongside some of the best people in tech. 💙

And it was great to see this follow-up from her supportive husband. I’m a firm believer that a marriage is a team, and kudos to Bob Cowherd for this tweet:

I have nothing but respect for Crawford’s drive, determination, and willingness to put in “crunch time.” I have nothing but praise for Cowherd’s supportiveness. Having worked for similarly careless, callous, and capricious bosses — they just didn’t come up from apartheid emerald money — I believe that Crawford’s intense dedication was wasted on Elon Musk.

My recommendation to any Twitter employee back in November was to leave, as I said in my November 7 post (5 days after Crawford’s “sleeping bag” tweet), Advice to laid-off Twitter employees being asked to come back. It even ends with the “sleeping bag” photo and this line:

If you can afford not to, don’t go back. You’re being asked to go back to Hell.

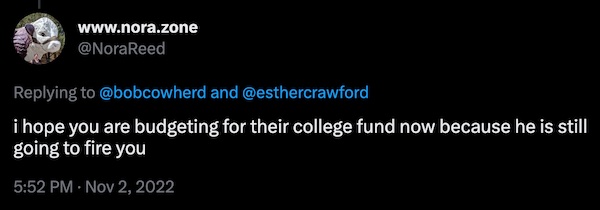

Some people on Twitter were more blunt — and in hindsight, prescient:

Loyalty to a company

I’ve had more than a few conversations — often over drinks, so these are backed by in vino veritas — where someone says that loyalty to a company is a sucker’s game. I think the truth is a little more nuanced than that.

A certain degree of loyalty to an employer who has earned it is actually a good thing. You’re more likely to be happy at work, and that’s important, as you’re that’s how you’re going to spend half your waking life from Monday through Friday. With this kind of loyalty comes two-way trust, and as Steven Covey puts it: Without trust, we don’t truly collaborate; we merely coordinate or, at best, cooperate. It is trust that transforms a group of people into a team.

I like and trust the company I work for and the team I work on. In fact, looking at the teams I’ve worked with in the past decade, the current one is my favorite. I like my manager, my manager’s co-managers, my “skip-level” manager, and the various C-level people, most of whom I’ve had the chance to meet (and even play accordion for). They have my loyalty — within reason — because I know that I also have their reciprocal loyalty — also within reason.

It’s clear to me that the organization isn’t a family. It’s a publicly-owned corporation that operates in the present-day economy. My relationship with the company is pleasant, cordial, and thanks to its culture, convivial, but I know it’s also transactional. Implicit in the employment contract between me and the company is the understanding that the basis of our relationship is that I give them my time and effort and they give me money.

Even with co-workers, managers, and C-level execs who I feel conduct themselves with decency and honor, my loyalty — which is considerable; I have Auth0 stickers on my accordion — is given with reasonable limits.

I would not extend that same loyalty to less decent, less honorable people. And I would most certainly not extend that loyalty to a vaingloriously venal weasel like Elon Musk.

Crawford’s “loyalty” was a gamble

While I am not in possession of the magic glasses that lets me see people’s true intentions, I’ve seen shit. And from the moment that Musk walked into Twitter HQ with a sink for comedic effect, Crawford has been doing exactly what one should do to get into the good graces of a petty, vengeful narcissist (who views most people as NPCs) that just spent billions on a criticism factory.

Consider this bit from the Financial Times piece:

When Musk first came to the San Francisco headquarters just before the deal closed, Crawford introduced herself in the Perch, Twitter’s on-site coffee shop, and secured a one-on-one meeting to discuss her ideas around payments and creators, according to multiple people familiar with the encounter.

And that “sleeping bag” photo? In the well-lit conference room? That’s somehow pristine clean even though everyone was in crunch mode? That ain’t no candid shot.

Also consider that Crawford grew up in a cult. In that kind of environment, you probably learn a couple of tricks on how to handle leaders who think they are the spokespeople for a higher power, or worse still, think they are that higher power.

Lest you think that I’m engaging in hyperbole by calling Elon Musk a narcissist, remember that he was so incensed that his Super Bowl tweet got only 9 million impressions compared to Joe Biden’s nearly 29 million that a “high urgency” message to @here on Twitter’s Slack was made to “any people who can make dashboards and write software” at 2:36 a.m. on the morning after the game. And let’s not forget that at a meeting to discuss the “lack of engagement” with his tweets, an engineer was fired for suggesting that public interest in Elon’s tweets had peaked and was now dropping.

I have worked at places whose mission I believed in, but whose management I did not. I believe that Crawford’s was a similar situation. And I took a similar approach, all the while readying not just Plan B, but the additional Plans C through G.

Keep this in mind…

Many people are going to dunk on Crawford for the next couple of days. Some of them will be from the Elon Musk fan club, who will say that she simply failed to deliver. Others will be Musk detractors, who will say that it’s what you get for working an egomaniacal autocrat.

Many of them will be the sort whose tendencies are to punish women for the sin of being ambitious. Keep that in mind.

So what are the lessons here?

Even if the purpose of this post was to dunk on Esther Crawford — and it isn’t — I would still be “punching up.”

Crawford came to Twitter by way of acquisition. Twitter bought the video chat startup she founded, Squad, in late 2020. While the amount wasn’t disclosed, a look at Twitter acquisitions shows that they haven’t bought any company for less than double-digit millions. She has a great resume, she can always point to that profile in Financial Times, and she’ll likely be featured in a “What Next?” piece in some other tech or business publication very soon. She can even trade on the story that she worked with tech’s biggest jackass.

Simply put: Crawford will most likely be fine.

This article is not really about her, nor is it for her. It is, most likely, for you, especially if you don’t have a six- or seven-figure cushion to fall back on when the going gets brutal at work.

In my opinion, the lessons to take away are:

- If you can help it, don’t work for assholes. If the option is available to you, try to work for and with people with at least some character. And try not to work for self-serving, whim-governed, spoiled emperors.

- If it can’t be helped and you have to work for an asshole, learn to manage them. And while you’re at it, formulate a plan to minimize your exposure from said asshole, or get away from them altogether.

- Favor high-trust environments over low-trust ones. Yes, there are a number of high-paying low-trust environments out there. In fact, the high pay is often used as a way of making up for the low trust. They might be great for your bank account in the short term, but they’re terrible in the long term.

- There’s a fine line between singing your company’s praises and bootlicking. Each of us has a different idea of where that line is drawn. And some of us will talk pretty loudly about it.

- Build a support network. A supportive spouse or partner can be a great help if you’re working at someplace like the current Twitter, and a network of peers can often be your key to escaping to a different organization.

Further reading

- Business Insider: One of Elon Musk’s most loyal employees was fired at Twitter. Here’s how she went from surviving layoffs to the chopping block in the span of a few months.

- Engadget: Twitter has reportedly laid off product manager Esther Crawford

- The Information (subscription required): Elon Musk’s Twitter Lays Off Top Lieutenant in Charge of Twitter Blue

- South China Morning Post: Twitter lays off dozens more workers, including executive who tweeted #SleepWhereYouWork after Elon Musk’s takeover

- TechCrunch: More layoffs at Twitter, and loyalist Esther Crawford isn’t spared

One reply on “Lessons from the “sleeping bag director” at Twitter who just got laid off”

[…] She’s one of the “Twitter 1.0” people who worked hard to get into Elon Musk’s good graces, which I wrote about in an earlier post, titled Lessons from the “sleeping bag director” at Twitter who just got laid off. […]