What is WebMatrix?

![]() By now, you’ve probably seen the tech news reports as well as Scott Guthrie’s announcement about WebMatrix, Microsoft’s lightweight web development web development system that packages a web development tool with a number of new web technologies:

By now, you’ve probably seen the tech news reports as well as Scott Guthrie’s announcement about WebMatrix, Microsoft’s lightweight web development web development system that packages a web development tool with a number of new web technologies:

- IIS Developer Express: a lightweight, free-as-in-beer web server with simple setup, runs on all versions of Windows and is compatible with the full-on version of IIS 7.5

- SQL Server Compact Edition: a lightweight, free-as-in-beer file-based database with simple setup that can be embedded within ASP.NET applications, supports low-cost hosting and whose databases can be migrated to the full-on version of SQL Server.

- ASP.NET “Razor”: A new view engine option for ASP.NET for easy and clean templating with a simple syntax. You can use Razor to embed C# or VB into HTML.

WebMatrix ties these goodies together in a nice simple package that the beginning web developer will find easy to use and that the pro web developer will find handy for building quick sites. These parts are also available individually to ASP.NET developers and will soon be available to ASP.NET MVC developers.

If you’re looking for a quick video tour of WebMatrix, chack out the Channel 9 video below:

Can’t see the video? You can download and install Silverlight or download the video in iPod, MP3, PSP, WMA, WMV, WMV (High) or Zune formats.

A Quick Look at WebMatrix’s Parts

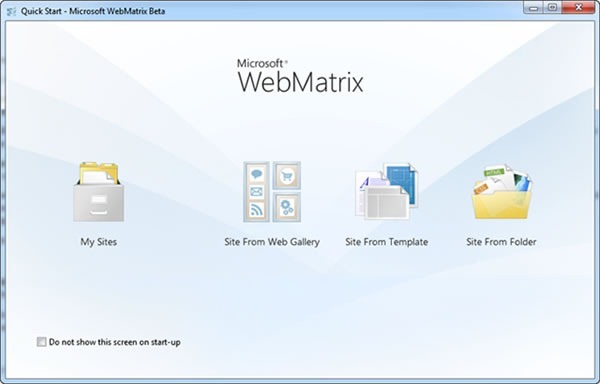

WebMatrix provides a simple, task-based interface for quickly creating web sites, both static and dynamic:

It makes it easy to include open source ASP.NET- and PHP-based web applications in your site:

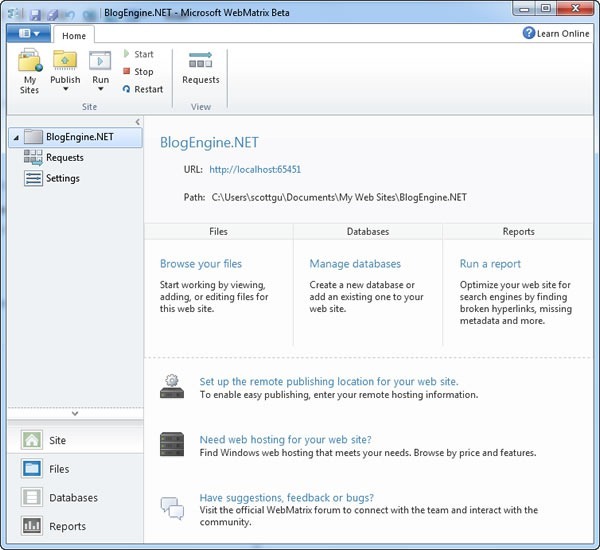

It’s also easy to manage applications in a WebMatrix site:

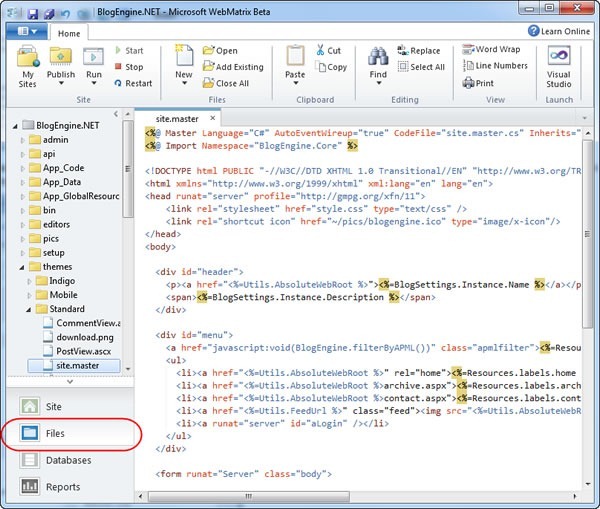

If you’d rather write your own web app in WebMatrix, you can do that too. There’s a rich file editor:

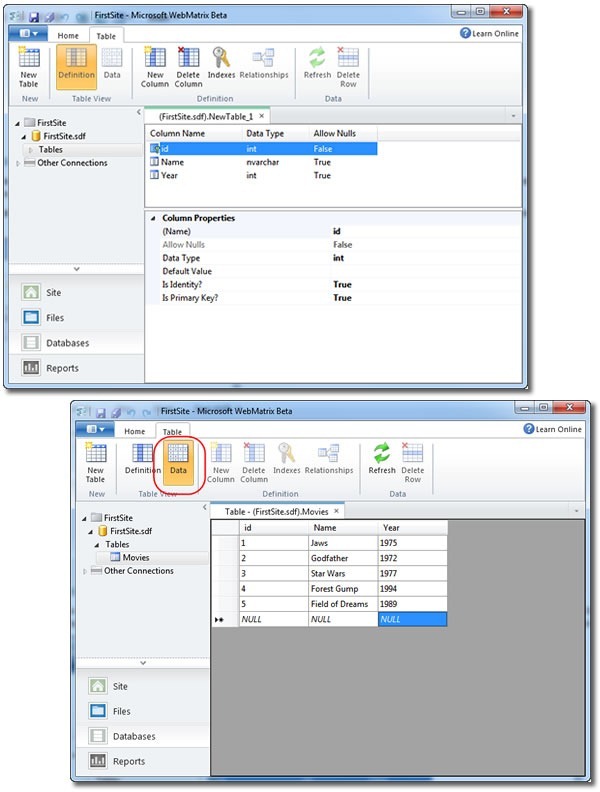

And database definition and management tools:

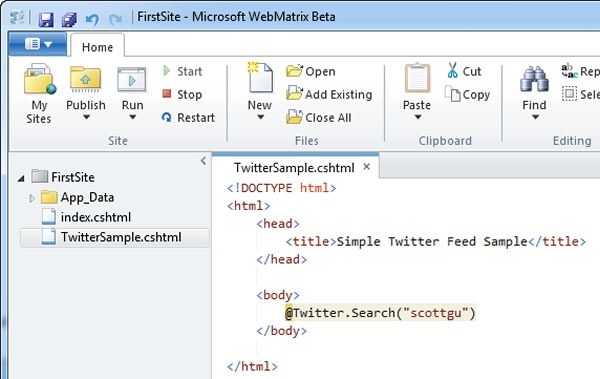

There’s also sample code and web helpers to make your life easier and show you what’s possible, such as this handy sample that makes it easy to make a Twitter client. Here’s the code that takes advantage of the sample:

…and here’s the result:

If you need to get hardcore, you can open your WebMatrix project in Visual Studio or even the free-as-in-beer Visual Web Developer 2010 Express:

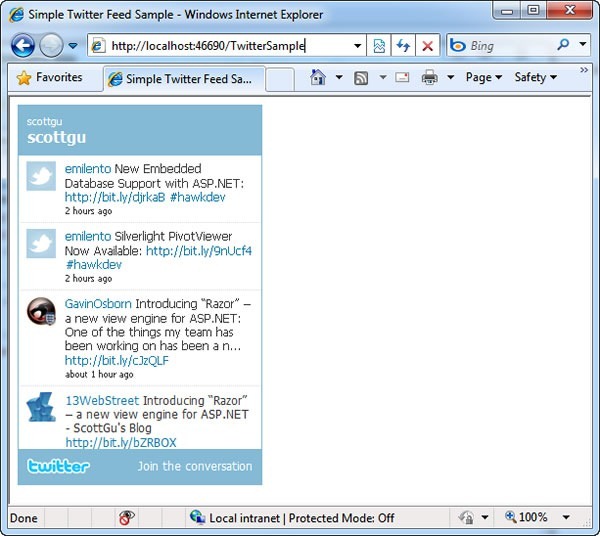

Previewing your WebMatrix site in multiple browsers is a snap:

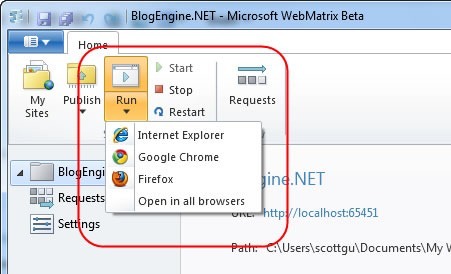

Deployment is nice and easy once you’re doing editing your site:

Find Out More

I haven’t had a chance to take WebMatrix out for a proper spin yet, but I’m hoping to over the next few days. It’s a collection of cool technologies (which I ‘ll also use in my regular ASP.NET MVC development) wrapped together by a nice, simple tool that’s great for the web developer who’s not working on enterprise sites. I can also see myself using it as a handy prototyping tool.

If you’d like to find out more about WebMatrix, take a look at these:

- The WebMatrix site

- Scott Guthrie’s blog article, featuring a very comprehensive tour of WebMatrix

- Channel 9 video: Simon Calvert and Scott Hunter show off WebMatrix and Razor’s syntax

WebMatrix has just been released as a beta and available for download right now! We want you to try it out and let us know what you think, because we’ll be refining it based on what you tell us.

This article also appears in Canadian Developer Connection.