Last week, I presented Kodu (pronounced “Code-ooh”) to a group of teachers and high school students at Corpus Christi Catholic Secondary School. Kodu is a system created by Microsoft Research for programming videogames without using a traditional programming language; instead, you use a combination of menus and visual programming. It was designed to be a gentle introduction to programming that would appeal to children, but many adults – myself included – have ended up getting drawn into it, spending hours constructing and tweaking game worlds.

Kodu was built using XNA, Microsoft’s framework, toolset and runtime environment for building games for Windows, Xbox 360 and Zune. It was released for the Xbox 360 last summer as an Xbox Indie Game; you can download it for 400 Xbox points — about 5 bucks – or you can try the free trial version (it’s time-limited, but full-featured). If you don’t have an Xbox 360, you can download the Windows version of Kodu for free.

Kodu’s a little tricky to describe – it’s one of those things that’s much easier to show rather than tell. Here are a couple of videos that should give you a bit of Kodu’s flavour. First, here’s IGN’s look at Kodu:

Here’s XNA Roundup’s review of Kodu:

Kodu was designed to be programmed with the Xbox 360 gamepad, which you can use if you’re programming it on the Xbox 360 or a computer (if you’re using a computer, you’ll need either a wired Xbox gamepad plugged into one of its USB ports or a USB adapter for your wireless Xbox gamepad). If you’re using Kodu on a computer, you have the additional option of using the keyboard and mouse.

This is the first of a series of articles on Kodu programming that will appear here from time to time. If you’ve got kids (or know some) who are curious about programming, or if you’re looking to try a completely different kind of programming, get Kodu on your Xbox or PC and give it a try!

In this first installment, I’ll show you how you can build a simple little program that lets you drive an avatar around a small world. In later installments, I’ll show you more game-like elements and the “code” for a game of mine called “Stupid Sparkling Vampire Game”.

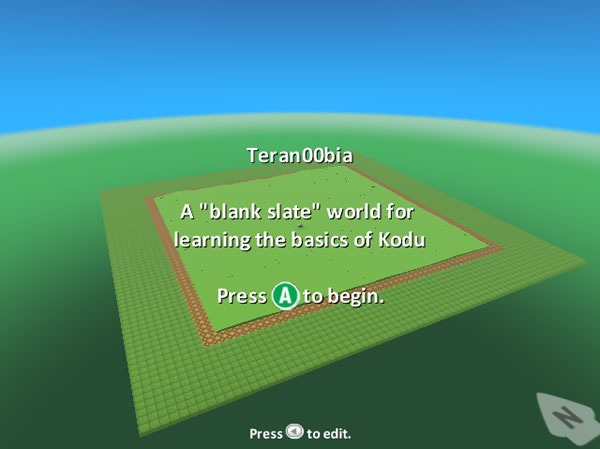

Touring Teran00bia

In addition to a programming “language”, Kodu provides you with tools for editing the worlds in which your games take place. I often start with a simple, no-fuss world that I created called “Teran00bia”. It’s a small, flat square world suitable for experimentation. If you have the Windows version of Kodu, you can download Teran00bia here. I can also share the Xbox 360 version, but you have to “friend” me on Xbox Live first – my gamertag is “Accordion Guy”.

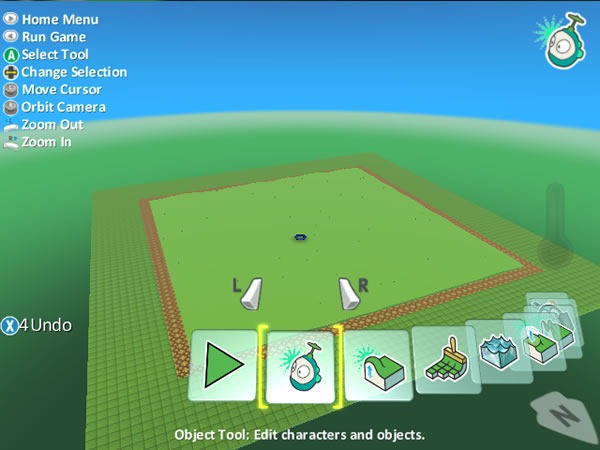

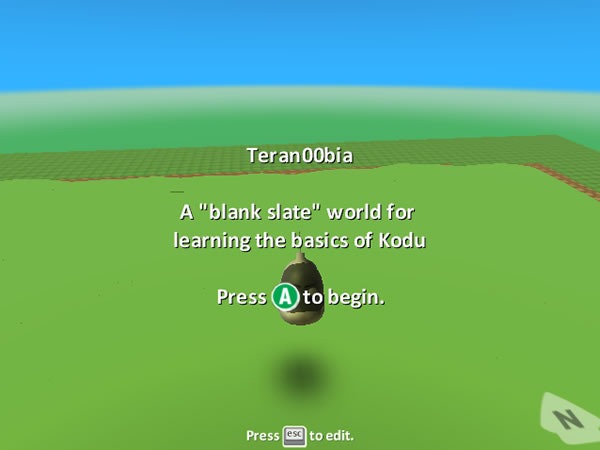

Teran00bia is a blank slate, a world with nothing in it. Here’s what it looks like when you load it:

In this exercise, we want to stick a single character – Kodu – into the world and allow the player to drive him around using the controller’s left stick.

To start programming, get into Edit Mode. Press the “Back” button on the gamepad to switch to Edit Mode. Your screen should now look like this:

In Edit Mode, the left thumbstick moves your “cursor” (the purple “donut”) around the world, while the right thumbstick changes your camera angle. You use the left bumper (that’s the button just above the left trigger) to zoom out and the right bumper (the button above the right trigger) to zoom in. The screenshot below shows a zoomed-in view of Teran00bia:

The floating icons near the bottom of the screen make up Kodu’s menu. You use the left and right triggers to scroll through the menu and the A button to select a menu item.

Select the Object Tool from the menu. It’s the second menu item from the left, and its icon is Kodu, who looks sort of like a blue fish with an antenna. When you select the tool, the Kodu menu disappears and you’re now using the object tool, as shown below:

The Object Tool lets you add items to the world or edit any existing ones. There aren’t any items in the world at the moment, so let’s add one. Use the left thumbstick to move the cursor to the spot where you want to place an object, then press the A button. The following menu will appear:

This menu lists the items available to you. Starting at the top and going clockwise, the items in the menu are:

- Kodu (the game system’s mascot, who can be used as either a player character or a non-player character)

- Apple (useful as a health power-up, but nothing stops you from making them poisonous or explosive)

- Bots 1 (a set of characters that can be used either as player characters or non-player characters)

- Bots 2 (more characters that can be used either as players characters or non-player characters)

- Objects (things that characters in the game can interact with, such as rocks, coins, castles and factories)

- Tree (another object that characters in the game can interact with – I have no idea why trees weren’t part of the set of Objects)

- Path (lets you draw paths which Kodu and the other bots can follow)

Use the left thumbstick to select Kodu from the menu, then press the A button to confirm the selection. A Kodu will appear:

You can move Kodu around by pressing the A button to select him, using the left thumbstick to pick a new location and then pressing the A button to drop him there.

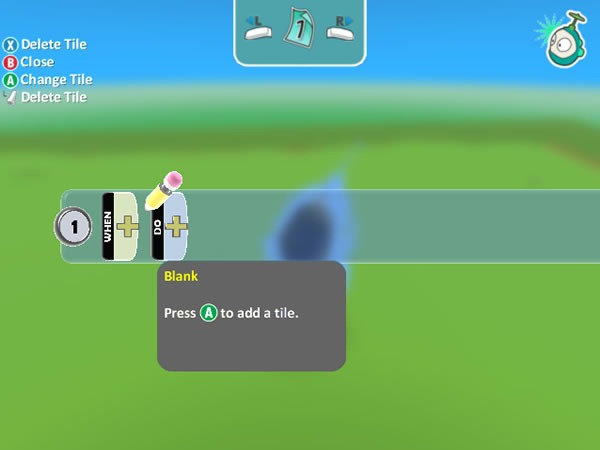

What we want to do is program Kodu to move in response to the left thumbstick, as is the convention for most Xbox 360 games. While Kodu is selected, press the Y button. The screen should look like this:

Every programmable object in the Kodu game system has a set of behaviours, each one having two parts:

- When, which describes the event that the object will respond to

- Do, which describes what the object will do in response to the event

The behaviours are numbered starting at 1 and are listed in order of descending priority – that is, behaviour 1 has first priority, followed by behaviour 2, then behaviour 3, and so on.

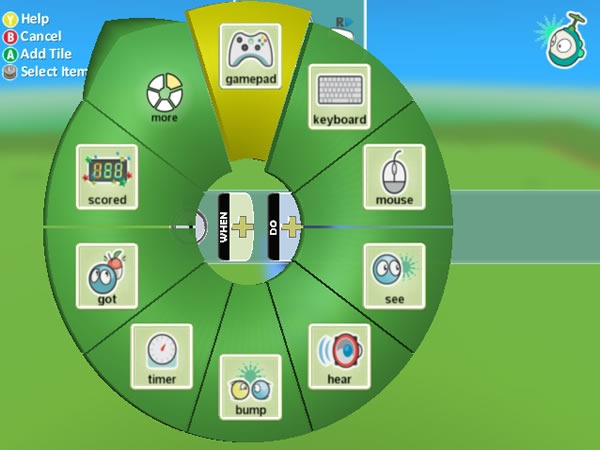

Your programming “cursor” is the pencil. Move the pencil over the “+” in the “When” part of behaviour 1 and press the A button. You’ll see a menu pop up:

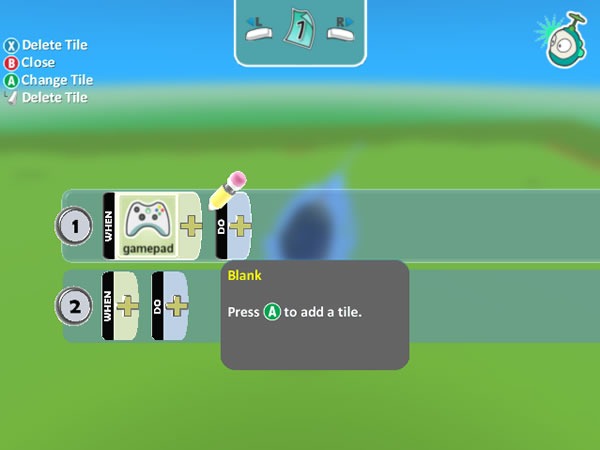

This menu lists the events to which Kodu can react. For now, we’re concerned with making him respond to the left thumbstick, which is part of the gamepad. Select “Gamepad” from the menu with the left thumbstick, then press the A button to confirm the selection. The menu will vanish and you’ll see that a “Gamepad” tile has been added to the “When” part of behaviour 1:

We need to specify which gamepad control Kodu should respond to. Make sure the pencil is over the “+” of the “When” part of behaviour 1, then press the A button. A menu containing various controls on the gamepad will appear:

Use the left thumbstick to select “L stick”, then press the A button. The menu will disappear and you’ll see that the “When” part of behaviour 1 has two tiles: “Gamepad” and “L Stick”:

We’ve just described an event that Kodu should respond to. Now it’s time to describe the response. Move the pencil over the “+” of the “Do” part of behaviour 1 and press the A button. A new menu will appear:

This menu lists responses to events. In this case, we want Kodu to move where the player tells him to move, which is specified by the left thumbstick. Select “Move” from the menu with the left thumbstick, then press A to confirm the selection. The menu will vanish, and you’ll see that a “Move” tile has been added to the “Do” part of behaviour 1:

We’ve now completely defined a single behaviour for Kodu: “When the player moves the left thumbstick, move in that direction”. It’s time to take our (admittedly simple) game for a spin.

Press the Back button to stop programming Kodu. You’ll now be in the Object Tool. Press the Back button again to return to Edit Mode, where Kodu’s main programming menu will become available. Use the left trigger to select Play Mode and press A to confirm the selection.

The program will start with the intro screen. Press A to dismiss the intro screen.

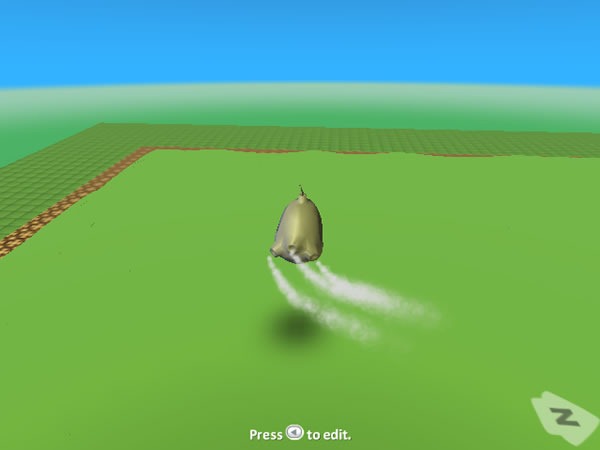

You’ll now be in the game world. Use the left thumbstick to move Kodu around:

Kodu moves, but he’s not so fast. Let’s look at a way to speed him up a little. Press the Back button to exit the program and return to Edit Mode. Use the triggers to select the Object Tool from the menu, then press the A button to confirm the selection.

Move the cursor under Kodu so that he’s selected:

Press the Y button to program Kodu. You’ll be return to his set of behaviours:

Move the pencil over the “+” of the “Do” part of behaviour 1, the press the A button. A menu will appear:

The menu will contain modifiers for the “Move” response. Select “Quickly” from the menu using the left thumbstick, then press the A button. The menu will disappear and you’ll see a “Quickly” tile has been added to the “Do” part of behaviour 1:

To make Kodu move even faster, you can add another “Quickly”:

…in fact, you can add up to three “Quickly” tiles to push Kodu to his maximum speed:

Play Around

I could cover more Kodu features, but you should use it the way it was meant to be used – experiment! Try adding other objects to the world and adding behaviours to them. Take a look at the programming behind the worlds that were provided with the Kodu game system (be sure to check out “Left 4 Kodu Classic”, a cute Kodu version of the zombie thriller game Left 4 Dead).

Links

- Kodu Game Lab for the Xbox 360 (400 Xbox points)

- Kodu Game Lab for Windows (free-as-in-beer)

- My “Teran00bia” world, handy for experimenting

- The Kodu Blog

- Generic Wars: A Kodu video tutorial showing you how to build a full game

- Planet Kodu has a couple dozen tutorials

- …and of course, keep an eye on this blog!