This article originally appeared in the Coffee and Code blog.

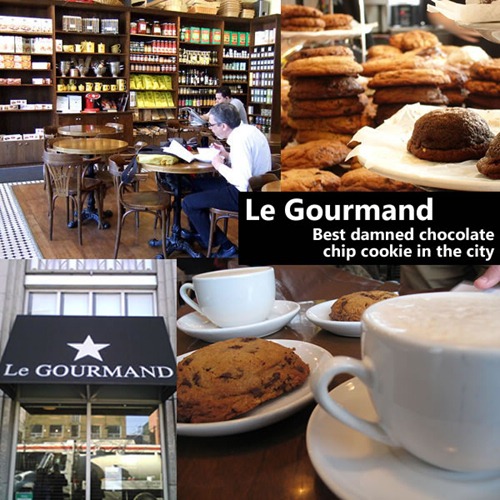

Yesterday’s Toronto Coffee and Code took place at Le Gourmand, a Parisian-style cafe near the Queen West/Spadina intersection, at the nexus of Chinatown, the funky boutique district and “clubland”. The neighbourhood is peppered of warehouses converted to offices that house a lot of “creative class” and geek offices. The area is a prime location for a Coffee and Code, and you can bet that I’ll host some more there.

The Coffee and Code took place immediately after another geek gathering, the Toronto Developer Lunch, a gathering of local geeks and techies for dim sum and conversation. A number of us went straight from the lunch to Le Gourmand.

This time, a couple of my fellow Microsofties joined me: Rodney Buike, IT Pro Evangelist, and David Crow, Startup Evangelist. Rodney brought some “I’m a PC” stickers with him and handed them out; even one of the Mac owners in the group even asked for a sticker!

At peak, there were ten other people, making our grand total a lucky 13.

Among the many conversation topics:

- ASP.NET MVC. I’ve been working my way through the “alpha” edition of Apress’ book, Pro ASP.NET MVC Framework, and have been enjoying it. We talked about the differences between ActiveRecord and LINQ to SQL – while ActiveRecord made ORM dirt-easy, LINQ to SQL offers some additional expressive power.

- David Crow and I talked about SQL Server, which is a bit of a change from our days in the open source world, where we’d typically use MySQL. SQL Server takes some getting used to after years of MySQL, but it’s a damned good database.

- The Lost and Damned, Grand Theft Auto IV’s downloadable new chapter, which may be the first game to feature male full frontal nudity.

- Windows Mobile development. I showed a dumb little “Hello World” application running in both the emulator on my machine and on my Palm Treo Pro. It’s part of my project to create a series of blog articles on writing apps for Windows Mobile phones and devices.

- Next week’s DemoCamp. David and I talked about the return of Toronto’s show-and-tell event for the tech community and the presentations that will take place.

- Visual Studio 2008. I fired it up and gave a quick demo.

- Le Gourmand’s chocolate chip cookies. The best in town!

- Game development in XNA and The Unfinished Swan. The Unifinished Swan is a game being prototyped in XNA and is an interesting combination of first-person shooter and painting game.

- Ruby, IronRuby, Python and IronPython.

- The upcoming Ignite Your Career webcast and EnergizeIT cross-country tour.

- The people we know who’ve been sent to the “body cavity search room” at U.S. Customs. The moral of the story: if you want to maintain anal sovereignty, be on your best behaviour at the border.

- Exploding office chairs. I think I’m going to work on the couch from now on.

- Hackers, which was recently on Space (Canada’s sci-fi channel).

- Johnny Mnemonic, another movie from around the same time as Hackers, and another movie that depicts the internet using a fly-by through a vector graphics cityscape.

- …and so many other conversation topics that were out of earshot.

All in all, the second Toronto Coffee and Code was a success. Stay tuned for an announcement of next week’s event!