The final speaker at last weekend’s FutureRuby conference was Jesse Hirsh, a Toronto-based internet consultant, researcher and “talking head” on CBC Newsworld and CBC Radio. As stated on the “About” page on his site, “his passion is for educating people on the potential benefits and perils of technology.”

His presentation, Fighting the Imperial Californian Ideology, was one of the less technical talks of the conference, whose topics ran the gamut from the expected – Ruby programming, programming languages and programming techniques – to topics you might not expect, such as nutrition for nerds, George Orwell and political languages, music and politics. In the end, it was all about building the future.

Here are the notes I took during Jesse’s presentation. I took the original notes and simply turned them into full English sentences and added context and links where necessary.

The Notes

- Books that influenced this talk include:

- Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson, which plays with a lot of ideas for a single novel, including:

- The overlap of technology and philosophy

- Ancient history and the near future (as seen from circa 1990)

- The concept of ideologies being viral

- Imperial San Francisco by Gray Brechin, which looks at the role that San Francisco has played in the American Empire

- Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson, which plays with a lot of ideas for a single novel, including:

- I spent my life studying Pax Americana and have noted how Californian ideology affects us all

- The latest version of Californian ideology comes from techies and technophiles:

- …starting with Stewart Brand

- and the going to Kevin Kelly

- and now Chris Anderson

- This presentation is about how Californian ideology affects us all

- “California”, as we consider it, has its beginnings in 1846

- The United States government sent surveyors down to Mexican territory and California in search of gold

- Minerals and mines are important to empires – there was never any successful empire that wasn’t in control of its own mines

- In 1846, the U.S. declared war on Mexico to acquire California

- 1849 marked the beginning of the Gold Rush

- We need to understand the term “Gold Rush” as it applies to people to work on the internet

- The dot-com boom of the late 1990s has often been referred to as a new gold rush, and there are parallels

- Both featured the wealthy and powerful destroying the environment

- The events of 1849 had many effects:

- It created an elite whose wealth was based on mining that ruled San Francisco

- It revolutionized the mining industry, with inventions such as the mineshaft

- The mineshaft in turn affected cities:

- At the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, the concept of the mineshaft was inverted and the skyscraper was born

- Offices in skyscrapers take mining principles and apply them to human labour

- In skyscrapers, instead of mining the earth, you mine people

- It created William Randolph Hearst

- Hearst was from a family whose wealth had come about from mining; he was a child of the ‘49ers

- Hearst mines are responsible for large amounts of environmental devastation:

- 8 out of 10 “Superfund Sites” that are too expensive to clean up

- Many environmentally devastated mine in Latin America

- In addition to the deleterious effects of its mines, Hearst is also responsible for The Spanish-American War, a conflict “engineered by Hearst“

- The sinking of the U.S.S. Maine [the “False Flag Conspiracy Hypothesis”]

- The takeover of the Philippines

- The prohibition of marijuana was also engineered by Hearst

- Hearst owned many wood pulp-based paper mills

- The production of paper using hemp was cheaper and was a threat to his business

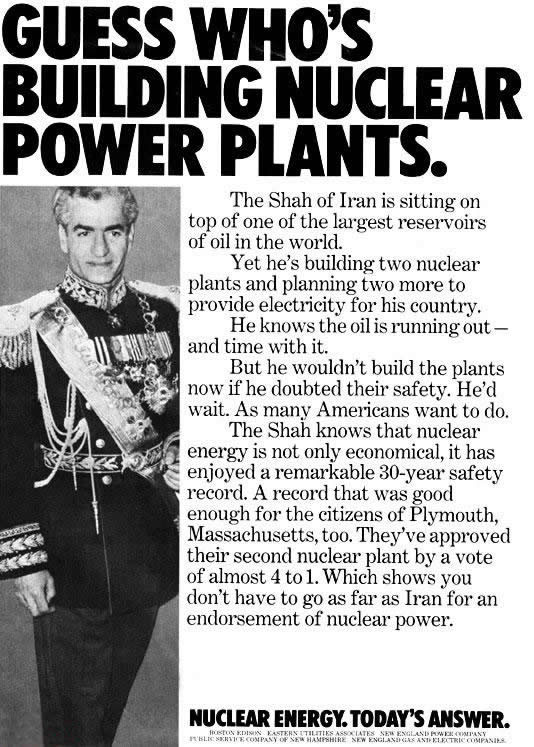

- California is the provider of armaments for the First and Second World Wars

- Berkeley and Stanford were schools that provided brains for the military

- California is the home of BALCO – the Bay Area Lab Cooperative – who are responsible for the designer steroids tainting Olympic and professional sports today

- The Californian ideology represents an elite community

- There is a perception among its practitioners that the world is theirs for the taking

- The ideology highlights a past that has been swept into myth

- That past includes a “Frontier ethos”, and the frontier was not a place for fairness

- The ideology came about around the time of the oil crisis of the 1970s, which is also when the dollar was de-linked from the gold standard and the U.S.’ influence was beginning to wane

- It was formalized by Brand, Kelly and the global business network

- It is a techno-utopian vision spread through publications like Mondo 2000 and later, Wired

- Kelly’s critiques sold a false mythology of a frontier where anyone can create a business plan

- This mythology is that of a biological techno-utopia, a hive:

- Problem: there are many worker bees, but only one queen bee

- It is a means by which the ruling class maintain their power

- The idea of the Long Tail is a meme within the California ideology

- It’s meant to engender complacency about being in the lower ranks

- In the Long Tail, it’s more of the same: a lucky few get all the cheese

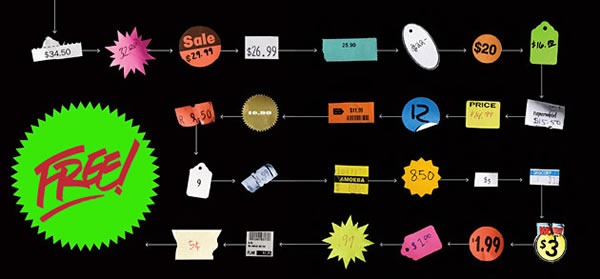

- The latest manifesto is Free

- It’s fundamentally wrong

- It’s not the “free” part that’s wrong

- “Free” is disruptive

- It’s part of the social-centric desire for freedom

- I went to the recent Free Summit held by TechDirt’s Mike Masnick, where Chris Anderson gave two keynotes

- Why did it take us 15 – 20 years of online economic business models cause us to realize how important social relations are important? The Communists have been saying this for years

- We are just realizing the value of social capital

- What’s missing is the political economy of Free

- I agree with a large portion of Free, except for one: its ethic of waste

- Waste is the central ethic of Free

- The thesis: Now that bandwidth, processor cycles and disk space are abundant, we must waste it. Only through waste will be we innovate

- The problem is that “waste is an ethic that has fucked us up royally”

- The counter to the waste ethic is “How do we make more with less?”

- That is the revolutionary potential of the internet

- This counter is revolutionary and anti-ideological

- “In the 21st century, there’s just culture”

- It involves holism, which is “a flip on relativism”:

- “I’m going to take the best shit available and integrate it into a coherent vision”

- Society is reaching a tipping point where all the stuff we techies do is mainstream:

- Twitter: trending topics on Twitter are determining what CNN covers

- Local crime: these days, news reports on local crime always include some element of internet-based activity (e.g. “The Craigslist Killer”)

- We are:

- Bowing to masters we don’t need (California)

- Following business models based on cultures we don’t live in (once again, California)

- Up against the California ideology, which professes freedom but delivers slavery

- We need to:

- Become community activists

- Help the next generation of AOLamers

- Remember when AOL joined the ‘net? Suddenly there was a flood of newbies and lamers “and the whole internet went to shit”

- “Most of the people using the net are fucking idiots”

- How do we, as the people who can create the tools, places and concepts, quickly get lamers into the metaverse of Snow Crash? It has a lot of positives:

- Universality: Everywhere, and accessible to everyone

- Geography: As a virtual reality environment, it provided waypoints and neighbourhoods for different purposes

- Space: Another byproduct of its virtual reality nature – it gave a sense of place as an means of organization, vs. the “cloud of shit” of our own internet

- We can create these neighbourhoods for people

- There is a big problem with "doing whatever is best for business”

- The free market “fucked us in the last year”

- Who can you trust?

- The people you know

- As a techie and participant in RubyFringe, you’re already doing it; just be conscious of it

- None of this is new

- It’s not about ideology, but practice

- What we think of as the nation-state is done

- Think of the city-state instead

- Think of (and participate in) the cities you live in

- The struggle for human rights continues. Which side are you on?

Discussion

FutureRuby attendee Pat Allan shares his thoughts on this presentation on his blog, Freelancing Gods, in his article titled FutureRuby and Californian Conflict.