Every week, I compile a list of events for developers, technologists, nerds, and tech entrepreneurs in and around the Tampa Bay area. The holidays are almost upon us, and there are a lot of holiday-oriented events this week.

Do you have an tech or entrepreneurial event in or around the Tampa Bay area that you’d like to see listed here? Drop me a line about it at joey@globalnerdy.com!

Monday, December 18

- Tampa Bay DevOps December Meetup — Puppet and how to misuse it @ Salesforce Tampa, 6:00 PM to 9:00 PM

- Cool ‘n Confident Toastmasters @ SPC – St. Petersburg/Gibbs Campus, 6:30 PM to 7:45 PM

- Pints & Pixels Gaming Night! @ Brew Bus, 7:00 PM to 11:00 PM

Tuesday, December 19

- Tuesday Night Gaming @ Cool Stuff Games, 5:00 PM to 8:00 PM

- Pinellas SQL User Group — Hillsborough & Pinellas Joint Holiday Party @ Courtside Grille, 6:00 PM to 9:00 PM

- Weekly Open Make Night @ Tampa Hackerspace, 6:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- Tampa Cybersecurity Meetup — SecureSet Programs Information Session @ SecureSet, 6:00 PM to 7:00 PM

- Learn Cybersecurity Tampa — Info Night @ Secureset, 6:00 PM to 7:00 PM

- Google Developers Group Sun Coast / Women Techmakers Tampa Bay / Tampa Bay Android Developers Group — Meet Tampa’s Tech Stars At Our Holiday Party! @ Malwarebytes, 6:00 PM to 9:00 PM

- Brandon eMarketing Groups — Internet Marketing for Business Owners @ O’Brien’s Irish Pub of Brandon, 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- Anime, Nerds & Geeks — Star Wars The Last Jedi – $5 Movies @ 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- Star Wars: Destiny Organized Play @ Armada Games, 7:30 PM to 10:30 PM

Wednesday, December 20

- Lean Coffee for All Things Agile (Downtown Tampa & Seminole Heights) @ FOUNDATION coffee co., 7:30 AM to 8:30 AM

- 1 Million Cups Tampa — Legend’s and Stories in Uniform Vetting America (SIUVA) @ Mark Sharpe Entrepreneur Collaborative Center, 9:00 AM

- OPEN/FREE Coworking for Veteran Entrepreneurs @ FirstWaVE Venture Center, 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM

- Tampa Entrepreneurs Network — How To Profit From Digital Currencies with Wright Thurston @ Online, 4:00 PM to 7:00 PM

- The Suncoast Linux Users Group — SLUG – Pinellas @ Pinellas Park Public Library, 6:00 PM to 8:00 PM

- Grand Gamers of St. Petersburg Board Game Night @ Critical Hit Games, 6:00 PM to 11:30 PM

- Crypto Investors Club – St Pete — RSVP to Attend @ Panera Bread, 6:30 PM to 9:00 PM

- St. Pete Makers — 3D Printer Maker Night hosted by FreeFab 3D @ NEW FreeFab 3D location, 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- Blockchain/Cryptocurrency Meetup: News, Q&A, Networking, Social @ BlockSpaces, 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- CigarCitySec Meetup @ Cigar City Brewing, 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- 3D Printer Orientation @ Tampa Hackerspace, 7:00 PM to 8:30 PM

- Anime, Nerds & Geeks — Star Wars The Last Jedi – $5 Movies @ 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- WordPress St. Petersburg — Meet and Greet / Q&A with Matt Mullenweg @ The Symphony Agency, 7:00 PM to 9:30 PM

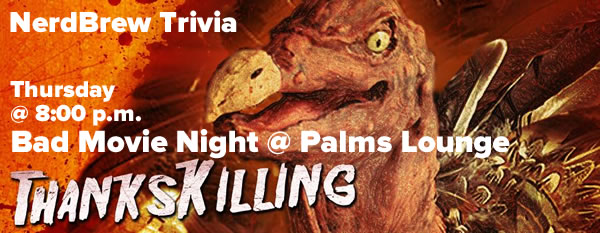

- NerdBrew Trivia: Star Wars — Part 2! @ Palms Lounge, 8:00 PM to 11:00 PM

Thursday, December 21

- Brandon Boardgamers — Let’s Game on Thursdays @ Panera Bread, 5:30 PM to 9:30 PM

- Lean Beer for All Things Agile @ Bad Monkey, 6:00 PM to 7:30 PM

- Fiverr MeetUp @ Vology, 6:30 PM to 8:30 PM

- Amazon Sellers in the Tampa Bay Area — Grab Dinner and Talk! @ 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- Largo Board Games Meetup — Francis Drake @ Michael & Nicky’s House, 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM

- CoderNight — Holiday Party and Group Challenge @ Malwarebytes, 7:00 PM to 9:00 PM

- THS Woodworkers Guild @ Tampa Hackerspace, 7:00 PM to 10:00 PM

- NerdBrew Trivia: Star Wars — Part 2! @ Palms Lounge, 8:00 PM to 11:00 PM

Friday, December 22

- Lean Coffee for All Things Agile (Westshore) @ Panera, 112 S Westshore Blvd, Tampa, 7:30 AM to 8:30 AM

- Café con Tampa — The Oxford Exchange Retail Story @ Oxford Exchange, 8:00 AM to 9:00 AM

Saturday, December 23

- Tampa Social Networking Meetup — Food & Craft Beer walking tours @ 1:00 PM to 4:00 PM

- Christmas Party! @ Critical Hit Games, 6:00 PM to 9:00 PM