For more, see SFGate’s article Why don’t Facebook and Google just embrace that they’re monetizing the third world?

This article also appears in The Adventures of Accordion Guy in the 21st Century.

“I hear you’re a free man,” the Microsoft manager said to me, clasping a hand firmly on my shoulder, in that “I’ve got your back, bro” sort of way, and not without a gleam of envy in his eyes.

The manager and I never directly worked together, but we both were on the Developer and Platform Evangelism team. To borrow a phrase from the U.S. Army, our job was to win over programmers’ and IT professionals’ “hearts and minds” and convince them of the benefits of using Microsoft tools and technologies. It was February 2011, and we were at a cocktail party at an internal conference in downtown Seattle. He’d heard about my separation.

“That’s right,” I said, taking another swig of some local microbrew and probably wincing a little. It had been a rough couple of months; she’d moved out around Christmas, and I landed in the hospital with a near-fatal case of the flu in January.

“There’s an upside,” he said, “there’s not a married man out there who hasn’t imagined what they’d do if all of a sudden they were single again, knowing what they know now.” He wasn’t the first married guy to remind of this fact, and like all of them, he was right: I was living the married guy’s combination fantasy and nightmare.

“So what are you going to do now?” he asked.

“I have been asking myself that same question for the past few weeks,” I replied. Weeks. The time since the ex-wife and I were under the same roof could still be measured in mere weeks. “I’ve decided the best thing for me to do is to emulate Tony Stark,” I said half-jokingly.

“Tony Stark…”, he said, without even the slightest glimmer of recognition on his face. “Who’s that?”

Like religious evangelism, technical evangelism requires an understanding of the culture in which you work. I would argue that this understanding extends to knowing its fictional icons. You’d probably (and quite rightly) wonder about someone who works in advertising who hasn’t heard of Don Draper, or a NASA employee who doesn’t know who you’re talking about when you mention Captain Kirk. At the time this conversation took place, there had been two wildly successful Iron Man movies, and even Forbes had done a piece on Tony Stark in their list of top fictitious rich guys.

Continuing my chat with the manager, who was a pretty nice guy and showed genuine concern about my major life change, I discovered that he’d be completely lost if you sat him in front of Visual Studio and asked him to write a “Hello World” application for the desktop, the web, or mobile, and system setup beyond pulling a laptop out of a box, plugging in an external monitor and connecting to wifi often confounded him. And yet, he was an overseer of Microsoft’s outreach to developers and IT pros, often called to speak in front of them and make hand-waving presentations of software and tech that he neither used nor knew how to fit together.

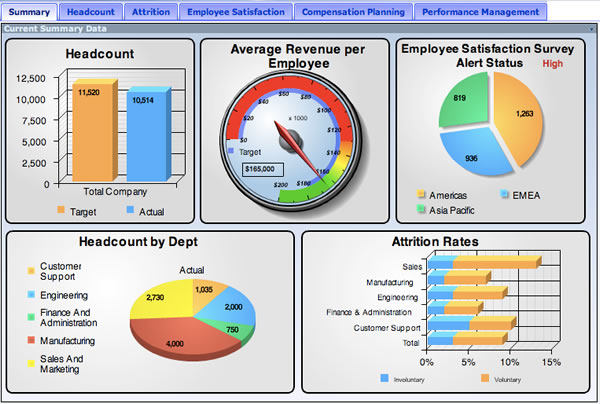

Further conversation led me to discover that the skill that had earned him his lofty level 63 position (like World of Warcraft, Microsoft has levels; also like World of Warcraft, the real fun begins at level 60) was that he could make the scorecard green.

At Microsoft, you’re only as good as your metrics. “Metrics” often translated into money. As the Stratechery article If Steve Ballmer Ran Apple puts it:

Employees were incentivized by dollars and cents in the form of bonuses and stock grants. Bonuses and stock grants were tied to a stack ranking system, that devolved your performance to a number. What was measurable mattered, particularly if it was measured in money.

The result is inevitable: Microsoft is a company filled with people motivated by measurables like salary, bonus, and job level. Anyone who isn’t would necessarily leave. Unsurprisingly, said people make choices based on measurables, whether those be consumer preferences, focus group answers, or telemetrics. The human mind is flexible, but only to a point.

…

Yet, if Apple’s success has proven anything, it’s that measurables aren’t the half of it. Things like design can’t be measured, nor can user experience. How do you price delight, or discount annoyance? How much is an Apple genius worth?

In the consumer market, it’s the immeasurables that matter. It’s the ability to surprise and delight, and create evangelists. It’s about creating something that developers demand access to, and that consumers implicity trust. The consumer market is about everything you can’t measure, everything Microsoft’s legion of mini-Ballmer’s can’t see and will never appreciate.

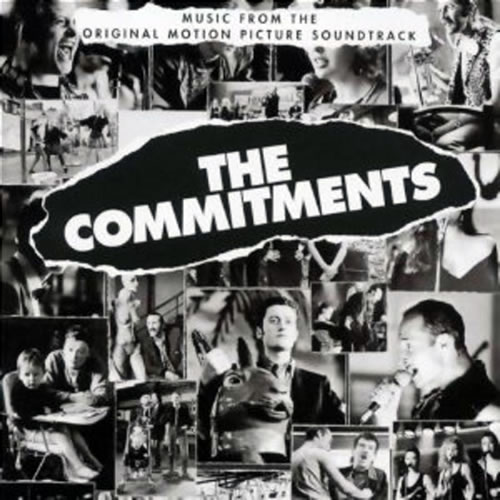

Once a year, you sit with your manager and come to an agreement on a set of commitments — a set of “deliverables” — for which either you individually, or as part of a team, are responsible for. As a developer evangelist, I had individual commitments that included doing x presentations in front of y people, discovering and publicizing a specified number of “success stories” where Microsoft development tools and platforms played a part, and hitting a target number of Azure sign-ups that could be directly attributed to me.

The aggregate commitments applied to both our own local teams as well as the developer evangelism group as a whole, and were things ranging from tech and tool adoption rates to “sat”, short for satisfaction, which as far as Microsoft was concerned, was an actual quantifiable property, derived from surveys and distilled into a single, mysterious, context-free number that seemed to bounce between 130 and 150 during my tenure.

There’s a mid-term review where you and your manager review your commitments to see how well you’re doing, and where you need to redouble your efforts. Near the conclusion of the fiscal year, which ends on June 30th at Microsoft, you write up how you well you think you met your commitments, your manager does the same, and after which the two of you have a long one-on-one meeting and compare notes. It’s at this meeting when you’ll get a very clear idea of which bucket you’re going to be put in: the 70, the 20, or the 10.

It’s often referred to in the tech press as “stack ranking”, but within the walls of Microsoft Canada, I’ve only heard it referred to as “70-20-10”. Those numbers refer to the three categories into which every manager at Microsoft had to place every one of his or her direct reports. These categories are:

Once a year, during our team offsite, the managers would take the time to explain this system, all the while taking great pains to explain why it was a good thing, in that sort of “toxic sludge is good for you” way. There are all sorts of problems with this sort of system, two of which were pointed out quite astutely by Bruce Lynn in the 70-20-10 blog:

My concern about the application of these ‘distributions’ is two fold. First, they are statistical constructs and most executives lack [the] numeracy to properly interpret and work with them. For example, while these distributions might generally apply over large numbers, no reasonable statistician would expect them to hold identically for smaller populations. In companies, sometimes these distributions are imposed on teams of just a handful of people. This imposition violates all sorts of statistical principles.

Also, one significant variable that such simplistic systems omit is the outcome of the group. A group that has achieved great things is likely to have different distribution of these categories than one that hasn’t. A world champion team might have more than ‘20%’ of its team as ‘All Star’ talent. In fact, the very fact of the skew to high performance could explain the overall team success. In another scenario, none of the team might be standouts (ie. no one at the 20% high achiever level), but the team work exceptional leading to a whole greater than the sum of the parts.

But more important than the clumsy application of such distributions is their application at all. These breakdowns are ‘descriptive’ stats, but misguided managers use them as ‘prescriptive’ rules. Misguided executives introduce policies which force managers to classify their people into such categories. The execs like the numbers because they are a nice, repeatable, McDonalds-like process which is easy to implement and understand on a superficial level. Unfortunately, it is often misapplied in specific instances. It is sort of like expecting a day with a ‘50% chance of rain’ to rain for half the day and be dry for half the day.

The other problem with 70-20-10 is that it can pit teammates against each other (luckily, this was not the case with my group). I’ve seen it create situations like the old joke about the two campers who encounter a hungry bear in the woods. The first camper says “I’m glad I wore my running shoes!”, to which the second replies “You can’t outrun a bear!” The first camper then says “I don’t have to outrun the bear. I just have to outrun you.”

If you managed to outrun the bottom 10, you could do very well. When I worked there, annual bonuses at Microsoft ranged from 6 to 60% of your base salary, and salaries at Microsoft are pretty good (in fact, people who leave Microsoft to work elsewhere often experience “reverse sticker shock” when they discover that most places outside The Empire don’t pay as well). My last bonus put me at a point where I could’ve bought a brand new sedan with cash.

When you combine bonus in the tens of thousands of dollars and tech culture, where Asperger’s syndrome is sometimes considered to be a badge of honour, you get antisocial, every-man-for-himself behaviour. In his Vanity Fair piece on Microsoft last year, Kurt Eichenwald wrote:

At the center of the cultural problems was a management system called “stack ranking.” Every current and former Microsoft employee I interviewed—every one—cited stack ranking as the most destructive process inside of Microsoft, something that drove out untold numbers of employees. The system—also referred to as “the performance model,” “the bell curve,” or just “the employee review”—has, with certain variations over the years, worked like this: every unit was forced to declare a certain percentage of employees as top performers, then good performers, then average, then below average, then poor. …

For that reason, executives said, a lot of Microsoft superstars did everything they could to avoid working alongside other top-notch developers, out of fear that they would be hurt in the rankings. And the reviews had real-world consequences: those at the top received bonuses and promotions; those at the bottom usually received no cash or were shown the door. …

“The behavior this engenders, people do everything they can to stay out of the bottom bucket,” one Microsoft engineer said. “People responsible for features will openly sabotage other people’s efforts. One of the most valuable things I learned was to give the appearance of being courteous while withholding just enough information from colleagues to ensure they didn’t get ahead of me on the rankings.” Worse, because the reviews came every six months, employees and their supervisors—who were also ranked—focused on their short-term performance, rather than on longer efforts to innovate.

By the time I had joined Microsoft, I had been blogging for seven years and decided to turn my skills and energies towards revitalizing the Canadian Developer Connection blog. I took it from a site with three posts a month to thirty posts a month, brought the readership up from dozens a day to thousands, often getting linked on Techmeme and occasionally garnering the attention of tech writers covering Microsoft, such as Mary Jo Foley. I became Microsoft Canada’s most prolific blogger, something that annoyed a manager who once called me into his office simply for him to express this annoyance: “You think you’re fucking hot shit, don’t you?” (To which I can now reply: “Hotter than you, chump. Hotter. Than. You.”)

70-20-10 didn’t just lead people to focus on the short term to the detriment of the long-term; it also made people very risk averse. One year, my team had the collective commitment of getting 800 people to sign up for an Azure (Microsoft’s cloud computing service) account. Some people committed to bring on 20, some went for 30, and a couple said they’d bring in 50. Here was Microsoft’s version of cloud computing, something that could rewrite the book on web services, and everyone was holding back for fear of not being able to hit that number and paying for it in the annual review. It’s this institutionalized fear that turned Microsoft from a creator of trends into a company that was content to chase them. What happened to the company whose mantra was the audacious “A computer on every desk and in every home, running Microsoft software?”

I thought the metric was meaningless. As far as I was concerned, a dozen high-quality accounts that used Azure for useful software, and often, would be worth more than a hundred sign-ups. In a fit of “screw it”, I put myself down for bringing in 400.

I got praise from my manager, who then reminded me that I didn’t have a plan for bringing in those numbers. It didn’t take long to work one out, though. After a chat with a friend who worked at Redmond, it became clear to me that all I had to do was get people to open a free Azure account and stick anything on it. I got a Silverlight expert I knew to make a web app that people could install into their Azure account, and got them to open Azure accounts by either:

In the process, I may have convinced one or two people who’d go on to use Azure for a project. The rest of them simply set up an account, installed the web app, and never logged back in again. In the end, what I truly did was give a few hundred people a shot at winning an Xbox, and gave several dozen a case of the coffee shits. It felt like a hollow victory. But I hit my target number and got my bonus!

The other effect of 70-20-10 is that I was constantly reminded by my manager to devote more effort to “my career”. By this, he didn’t mean brushing up on my tech skills, or my presentation skills, or my writing — which he did, anyway, because he was a great manager. He was talking about “managing up”, building relationships with the higher-ups and across departments with the people who could bring me from a level 61 employee to level 62…and beyond!

I understand and appreciate the value of such relationships, and I’m a pretty good schmoozer. But the level to which this sort of relationship building was encouraged within Microsoft was almost sociopathic, and the internal guidance kept pushing us to spend what I think was too much time building alliances, as if we were competitors on the island on the reality TV show Survivor. Partnerships, alliances, joint projects, and so on all had an undercurrent of “what can this person or team do for my career”?, “How can this guy help get to level 62?”, “How can so-and-so help me keep my scorecard green?”, and as Mini-Microsoft put it, “Influence if you can, scare if you must”.

I was trying to be Scott Hanselman, and but they wanted Dwight K. Schrute.

Click the “reply all” screenshot to see it at full size.

The dreaded “Reply All” button claimed a victim at Microsoft today when Roy Levin, distinguished engineer at MS Research in Silicon Valley, commented in response to Steve Ballmer’s internal email announcement that he would retire sometime in the next 12 months.

Here’s the full text of his response:

Right. Maybe there’s a back story. The market likes the news, which is interesting, given that the successor isn’t known. Now the speculation shifts into high gear.

While embarrassing, it’s hardly career-ending. He could’ve said “Don’t let the door hit your ass on the way out, Monkey-Boy!” As Valleywag observes, it’s to Levin’s credit that he sent his reply from a Windows Phone (“Second place in the second world!”).

At this stage in the game, email clients are not new things. We’ve had decades of experience with them, and we know what works, what doesn’t, and what the pitfalls are, including the dangers of “Reply All”. Many desktop clients, including Microsoft’s own Outlook, have some kind of mechanism that double-checks with you before you reply to everyone on a mass email. For some reason, this handy safety feature doesn’t seem to be built into mobile email apps. Given that an increasing portion of our email is sent while on the go, it’s high time that we made the email apps on our phones as least as “smart” as their desktop counterparts.

Yours Truly and Steve Ballmer at a Microsoft Canada town hall, October 2009.

You’re going to be hearing about this all day today, so you might as well read it here. A news release from Microsoft’s PR site published today announced that CEO Steve Ballmer will step down sometime in the next 12 months.

Here’s the Ballmer quote from the release:

“There is never a perfect time for this type of transition, but now is the right time,” Ballmer said. “We have embarked on a new strategy with a new organization and we have an amazing Senior Leadership Team. My original thoughts on timing would have had my retirement happen in the middle of our company’s transformation to a devices and services company. We need a CEO who will be here longer term for this new direction.”

As a former Microsoftie, I’ve seen two Steve Ballmers. There’s the Steve Ballmer the public saw, the blustery, manic, chair-throwing, “Developers, developers, developers, developers” guy, who tragically underestimated the effect that the iPhone would have on the industry and Microsoft’s fortunes, and the CEO oversaw Microsoft through its “lost decade”. Then there’s SteveB — the name often used to refer to him in internal emails — who had a solid grasp of just about every aspect of the business. At the internal town hall meeting where the picture above was taken, he gave intelligent answers to esoteric questions from people from wildly different departments at Microsoft Canada. He’s also managed to keep Microsoft rolling in money; in Microsoft’s 2Q 2013 (their fiscal year begins on July 1st; their 2Q 2013 is 4Q 2012 on the calendar), they posted a record revenue of $21.5 billion.

There has been a vocal chorus of shareholders who’ve been calling for Ballmer’s resignation, and there will likely be champagne corks popping this afternoon. CNET reports that Microsoft shares have jumped up 8% in pre-market in response to the news.

John Zissimos posted the following graph on Twitter with the tagline “What Ballmer retiring from Microsoft looks like on a stock chart”:

Click the graph to see it at full size.

The natural question is “Who will Ballmer’s successor be?” Steve Sinofsky has long been seen as Ballmer’s eventual successor and would’ve been the most likely choice, if he hadn’t left the company back in November.

Microsoft’s notorious insider blogger is frickin’ tickled pink. He also astutely points out:

To me, this throws the whole in-process re-org upside down. Why re-org under the design of the exiting leader? Even if the Senior Leadership Team goes forward saying that they support the re-org, it’s undermined by everyone who is a part of it now questioning whether the new leader will undo and recraft the decisions being made now. I’d much rather Microsoft be organized under the vision of the new leader and their vision.

I’ll close with the observation that the choice to make the announcement on a Friday — and a Friday near the end of August, when many people are on vacation — is noteable. In the world of PR, Friday is “Take Out the Trash Day”, when you make announcements that you want buried. Here’s an exchange from The West Wing that explains the idea:

Donna: What’s take out the trash day?

Josh: Friday.

Donna: I mean, what is it?

Josh: Any stories we have to give the press that we’re not wild about, we give all in a lump on Friday.

Donna: Why do you do it in a lump?

Josh: Instead of one at a time?

Donna: I’d think you’d want to spread them out.

Josh: They’ve got X column inches to fill, right? They’re going to fill them no matter what.

Donna: Yes.

Josh: So if we give them one story, that story’s X column inches.

Donna: And if we give them five stories …

Josh: They’re a fifth the size.

Donna: Why do you do it on Friday?

Josh: Because no one reads the paper on Saturday.

Donna: You guys are real populists, aren’t you?

On Monday, I posted the first of my fortnightly — that means “once every two weeks” — tutorials covering iOS development. If you’ve got some experience with an object-oriented programming language, and better still, any experience with an MVC application framework, these tutorials are for you!

On Monday, I posted the first of my fortnightly — that means “once every two weeks” — tutorials covering iOS development. If you’ve got some experience with an object-oriented programming language, and better still, any experience with an MVC application framework, these tutorials are for you!

The first tutorial covered a simple “Magic 8-Ball” app, where you’d tap a button, and it would display a randomly-selected answer to a “yes or no?” question. The program is pretty simple, and that’s a good thing — that way, it doesn’t get in the way of showing how to use Xcode, Objective-C, the various frameworks that make up Cocoa Touch, and so on.

While the main tutorials will appear every fortnight, from time to time, I’ll post supplementary articles in which I’ll expand on a topic covered in the tutorial or make an improvement to the app. This is one of those supplementary articles.

In the “8-ball” app created in the tutorial, the answers that the app can randomly choose from are defined in the model object’s constructor, shown below:

// DecisionMaker.m

// ... (other code here) ...

- (id)init

{

self = [super init];

answers = @[

@"Yes.",

@"No.",

@"Sure, why not?",

@"Ummm...maybe not.",

@"I say \"Go for it!\"",

@"I say \"Nuh-uh.\"",

@"Mmmmmaybe.",

@"Better not tell you now.",

@"Why, yes!",

@"The answer is \"NO!\"",

@"Like I\'m going to tell you.",

@"My cat\'s breath smells like cat food."

];

return self;

}

// ... (other code here) ...

It works, but I get a little uncomfortable when hard-coding these sorts of values in this fashion. I’d much rather populate the array of answers by reading the contents of some kind of file or resource that isn’t part of the code. This approach typically makes the code more maintainable, as it makes the code less cluttered with data, and editing resource files is less likely to break something than editing code.

plists, a.k.a. property lists, are XML files used in Mac OS and iOS to store data for things like initialization, settings, and configuration. Plists can hold the following types of scalar data:

Within a plist, any piece of data can sit on its own, or be organized into these collections:

Here’s a quick plist example. It has a single array that contains the 1977 members of the Superfriends:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN"

"http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<array>

<string>Superman</string>

<string>Batman and Robin</string>

<string>Wonder Woman</string>

<string>Aquaman</string>

<string>Wonder Twins</string>

</array>

</plist>

Within Xcode, plists can be read and modified using a nice editor, which saves you the trouble of entering XML tags and lets you focus on the data instead.

In this exercise, we’re going to replace the 8-ball app’s hard-coded array of answers with a plist, and then initialize that array with the data in the plist.

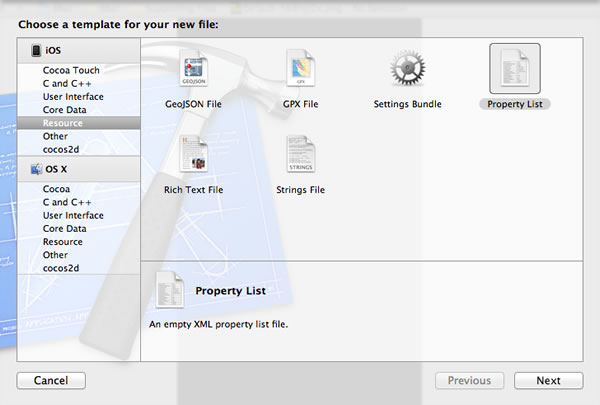

In the menu bar, select File → New → File…. You’ll see the following appear:

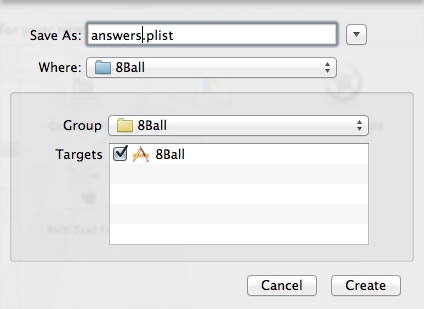

In the left sidebar under the iOS section, select Resource. Then, from the main view, select Property List, then click Next. You’ll be taken to this dialog box:

Give the file a name in the Save As: text box; I named my file answers.plist. Click Create to save the plist to your project.

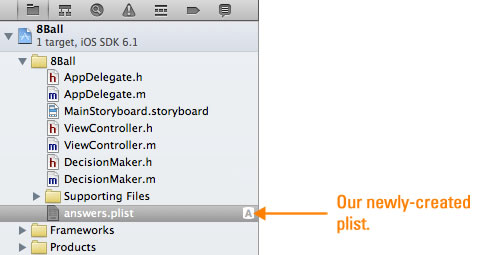

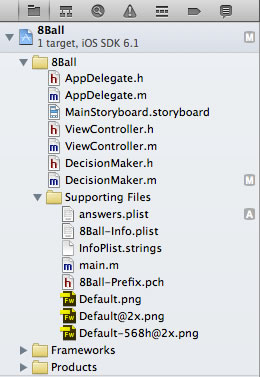

answers Array with the plistYour Project Navigator should look something like this:

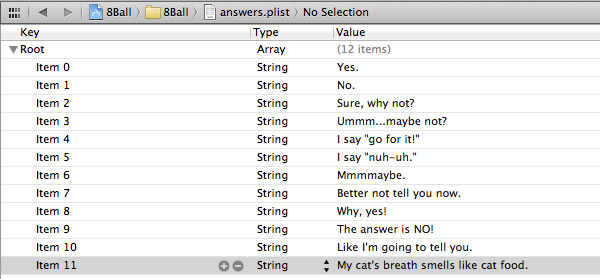

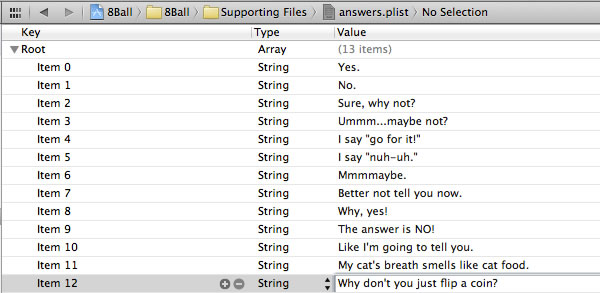

Select the plist in the Project Navigator. The plist editor will appear in Xcode’s main pane. Use it to enter the 8-ball answers into the plist as shown below:

Now that we’ve defined the plist, let’s change the constructor of the 8-Ball’s model, DecisionMaker, so that it reads the plist and feeds it into the answers array:

// DecisionMaker.m

- (id)init

{

self = [super init];

NSString *answersListPath = [[NSBundle mainBundle] pathForResource:@"answers"

ofType:@"plist"];

answers = [NSArray arrayWithContentsOfFile:answersListPath];

return self;

}

Let’s take a look at the new code line by line:

NSString *answersListPath = [[NSBundle mainBundle] pathForResource:@"answers"

ofType:@"plist"];

We need the list of answers, so we need to access answers.plist. It lives in the main bundle.

A bundle is a directory with a hierarchical structure that holds executable code and the resources used by that code. NSBundle is the class that handles bundles, and the mainBundle method returns the bundle that holds the app executable and its resources, which in the case of our 8-Ball app, includes answers.plist. The pathForResource:ofType: method, given the name of a resource and its type, returns the full pathname for that bundle.

Once we know the pathname for the bundle, we can construct the path to answers.plist, which is what the second line does.

answers = [NSArray arrayWithContentsOfFile:answersListPath];

arrayWithContentsOfFile is a handy method: given the path to a file containing a plist representation of an array, it will use the contents of a file to fill the array.

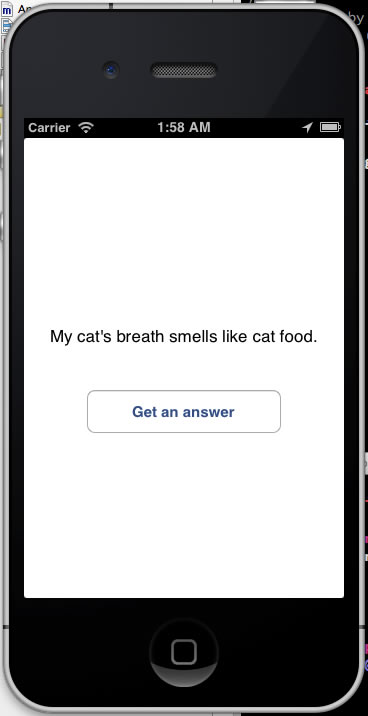

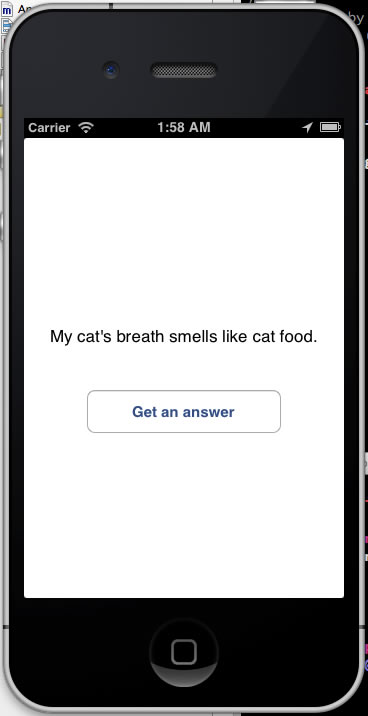

The app is ready to go — fire it up, and it should look like this:

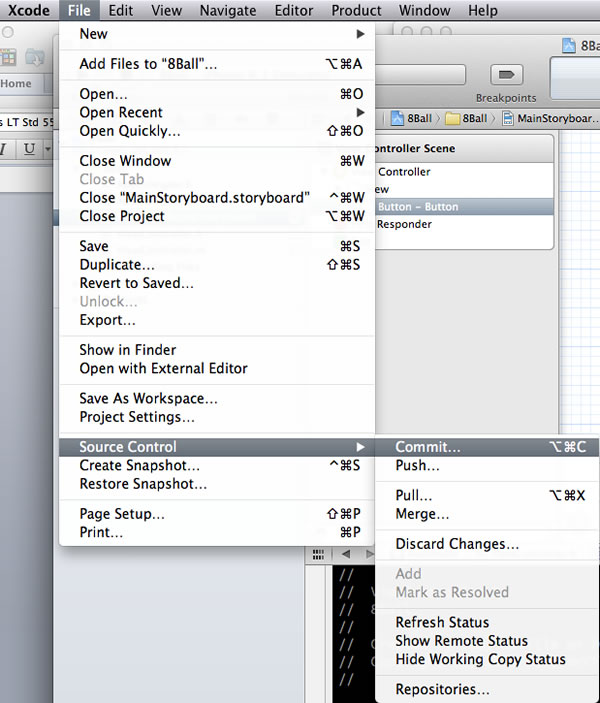

This is a small project, so it doesn’t have too many files. Even at this size, it’s good to keep its component files organized. Let’s put answers.plist into the Supporting Files folder, where the other resource files in the project live. Moving it is simply a matter of dragging and dropping in the Project Navigator, which should look something like this once you’ve moved answers.plist:

Run the app again. It still works, even though answers.plist is in now in the Supporting Files folder, the folders are just a convenience for you, the developer, to organize files into manageable groups.

You’ve now got an app that loads its gets it answers from a plist rather than via a hard-coded array. You can even add new answers…

At this point, it’s a good idea to commit this change to the repository. Call up File → Source Control → Commit… from the menu bar, enter an appropriate commit message (I used “Answers are now read from answers.plist instead of being hard-coded.”) and commit your changes. If you’re not in the habit of using source control, get into it now. It will save you a lot of pain.

One of the gems in Toronto’s local indie/startup tech outfits is Unspace, whom I’ve often referred to as “local Ruby heroes”. They’re a small company that’s had such a disproportionately big effect on the world of software development, from producing people who’ve gone on to 37signals and Microsoft, to putting together some of the best developer gatherings ever held — RubyFringe, FutureRuby, Technologic, Throne of JS, and Embergarten — to generally buoying the local tech scene with events like Ruby Job Fairs, Rails Pub Nite and gatherings on their rooftop patio above the heart of the Queen/Spadina district. And yes, they also write great software for their clients.

One of the gems in Toronto’s local indie/startup tech outfits is Unspace, whom I’ve often referred to as “local Ruby heroes”. They’re a small company that’s had such a disproportionately big effect on the world of software development, from producing people who’ve gone on to 37signals and Microsoft, to putting together some of the best developer gatherings ever held — RubyFringe, FutureRuby, Technologic, Throne of JS, and Embergarten — to generally buoying the local tech scene with events like Ruby Job Fairs, Rails Pub Nite and gatherings on their rooftop patio above the heart of the Queen/Spadina district. And yes, they also write great software for their clients.

In the most recent post on the Unspace blog, Unspace CEO Meghann Millard (pictured above) wrote about how an electrical fire broke out at Unspace last week, reducing their wonderful workspace from this:

Software developers gather at one of Unspace’s rooftop parties.

Make a note of the pinball machine.

Yes, I know these are all party pics, but they were taken at Unspace, and they know that programming is a social activity.

The crowd gathering at “Technologic” (one of their events), just before the presentations.

to this:

Luckily, no one was hurt. Eric, who helps keep the office in working order, was on the rooftop and trapped as a result of the fire breaking out. He managed to escape into a neighbouring apartment, evacuate its occupants and call 911.

While a burned-out office is a setback, Unspace is unbowed. After a quick gathering for lunch, the team set off to continue working from home, and Meghann’s working on securing some new space. She writes:

Oftentimes, I think people believe the byproduct of a great company culture is just what work can be produced when you provide great incentives, developer autonomy and personal flexibility. By contrast, I think I’ve finally identified where Unspace differentiates itself in this space — the sense of family inherent to a very carefully curated team – who cares for one another as much as their respective craft — is what ensures the gears keep turning through any crisis.

Of all things that have happened in the history of Unspace, I think this is what I’m most proud of. All we lost in the end was some stuff and a pile of bricks, and I’m very much looking forward to building “Newspace” with the team over the forthcoming weeks.

I can think of more than a few businesses that can learn from Unspace, who understand the importance of building a good company culture. It flows into everything, from the great work that they do for their customers, to the way that the people there feel a sense of family, ownership, and responsibility, to the positive effects they’ve had not just on Toronto’s technology community, but the world’s (seriously). They pulled together, and I have no doubt that they’ll pull through this situation.

Go and read their blog entry about the fire and the aftermath, and if you run into them in person or online, give ’em your love and support. They’ve earned it, and they have mine.

This article also appears in The Adventures of Accordion Guy in the 21st Century.

Jennifer Dewalt, burning the midnight oil.

Click the photo to see the source.

A couple of weeks back, I wrote about Jennifer Dewalt, who took on a big challenge. She had little or no programming education or experience but wanted to become a web developer, so she set out to learn the hard way: by making “180 web sites in 180 days”. She put aside enough money to work on this project full-time in some space in San Francisco in a developer-rich workspace.

A couple of weeks back, I wrote about Jennifer Dewalt, who took on a big challenge. She had little or no programming education or experience but wanted to become a web developer, so she set out to learn the hard way: by making “180 web sites in 180 days”. She put aside enough money to work on this project full-time in some space in San Francisco in a developer-rich workspace.

On Day 1 (April 1st), she made the homepage for her “180 sites” project in plain old HTML. Since then, she’s progressed and learning Ruby, Rails and JavaScript as she builds her apps. As of the evening of Sunday, August 18th, she’s on Day 140, with a web app that reports what your IP address is. You can see the master list of her projects on her project page, find out more as she chronicles her work on her blog, and get the source for all her projects from her GitHub account.

Dewalt’s determination, perserverance, and all-out chutzpah is admirable, and the way she framed her mission is quite clever. There’s nothing like a deadline to motivate you, and having to build a new project every day for six months forces you to constrain each one’s scope. The “build early, build often” approach also takes advantage of the idea behind the adage of “practice makes perfect”, which was put quite well in the book Art and Fear:

The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups.

All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality.

His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: 50 pounds of pots rated an “A”, 40 pounds a “B”, and so on.

Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot — albeit a perfect one — to get an “A”.

Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity.

It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work-and learning from their mistakes — the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.

My home office, pictured late Friday night.

I’ve decided to take up my own project along the same lines as Jennifer Dewalt’s. I’m going to publish an iOS development tutorial fortnightly — that is, once every two weeks — in which I walk the reader through the exercise of building a basic iPhone/iPad/iPod Touch app, explaining what I do along the way, and publish my code on my GitHub account.

I’m calling this series:

In order to follow along with iOS Fortnightly Tutorials, you’ll need some kind of Mac OS X computer that’s capable of running Xcode, the development tool. You’ll also need to get Xcode, which is available for free at the Mac App Store. It would help if you also had an iOS device and an iOS Developer account with Apple (you need one to deploy apps to iOS devices), but many of the projects in the tutorial will work just fine in the simulator.

These tutorials are best suited to people who’ve had some experience developing in any object-oriented programming language, from JavaScript to any of the standard suite of interpreted scripting languages (Perl, PHP, Python, or Ruby), or to compiled languages that often call for IDEs, such as C#, Java, or Visual Basic. Many of the principles that you’ve picked up in these languages will have some kind of analogue in Objective-C.

Unlike many tutorials, I’m not going to rehash what loops, and branches are, or explain what object-oriented programming is. I’ll explain stuff that would be new to someone just getting into Objective-C, Xcode, iOS, and Cocoa Touch‘s APIs. if you can’t quickly whip up FizzBuzz in the programming language of your choice, this programming tutorial series is probably not for you.

If you grew up in North America, you’re probably familiar with the novelty item known as the Magic 8-Ball. You ask it a question that can be answered with “yes” or “no” and turn it over. A multi-sided die suspended in blue liquid rises to a clear window, revealing a random answer. If you haven’t ever tried on before, here’s an online version that’s been around for ages.

The Magic 8-Ball has been a staple of programming exercises since computer programming courses have existed. It’s also been a quick little programming exercise for learning how to program in new languages or on new platforms. I’ve even used it as a candidate in a job interview. When I talked to Pebble about becoming their developer evangelist over a two-day visit to Palo Alto last summer (yes, the smartwatch company that raise $10 million on Kickstarter), they tested me by making me write a tutorial for programming their previous smartwatch, the InPulse, and I chose the Magic 8-Ball as my example, which I posted on GitHub.

I figured that an iOS version of my Magic 8-Ball tutorial would be a good start, and if you’re new to iOS development, you might find it useful too!

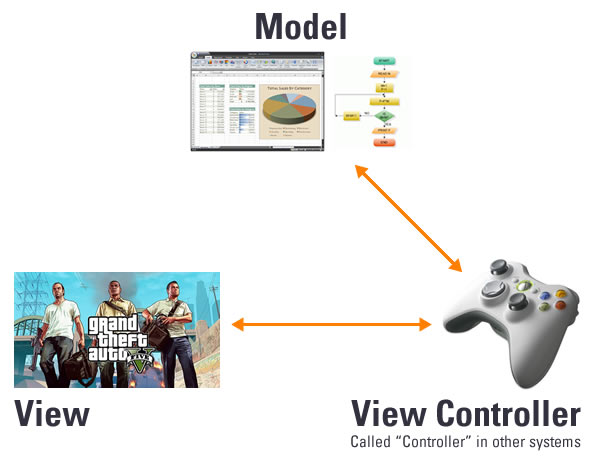

Most programming frameworks for developing interactive applications are based on some variation of the MVC — that’s Model-View-Controller — pattern. The general idea is the interactive applications are the result of three categories of objects working together:

iOS programming is generally based on the MVC pattern:

NSObject, the class from which all Objective-C classes ultimately are derived.UIView and a number of subclasses based on it — you can use these or subclass them.UIViewController and a number of subclasses based on it — again, you can use these or subclass them. These are often referred to as view controllers.If you’re comfortable with the concept of MVC, whether from client-side frameworks like Ember.js, or server-side frameworks like CakePHP, Django, or Rails, or from desktop app development, you’ll find the MVC aspect of iOS development familiar.

Time to get started!

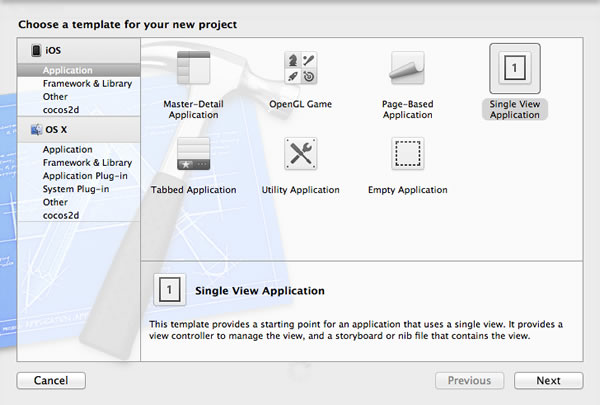

Let’s start with a new project. From the menu bar, choose File → New → Project…. You’ll see this:

This first step is to specify what kind of project you’re building. Based on the selections you make, Xcode will pull together the appropriate frameworks and set up a basic code that will form the “skeleton” of your app.

Our “8-Ball” app is an iOS app where everything happens in a single screen or view, so we’ll make it a single-view app. Here’s how you specify this:

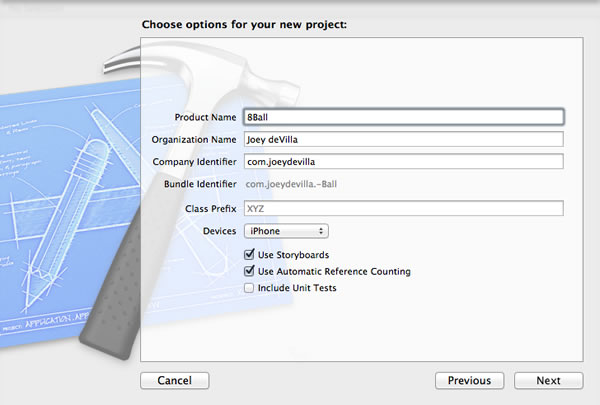

Click Next to proceed to the next step:

The second step in creating a new app is to choose a few options. Here are the mandatory bits:

Xcode automatically fills in the Organization Name and Company Identifier fields based on the business name from the “Me” entry in your Mac’s Address Book application. For now, go with these; at this point, they’re not important.

Click Next to proceed to the next step:

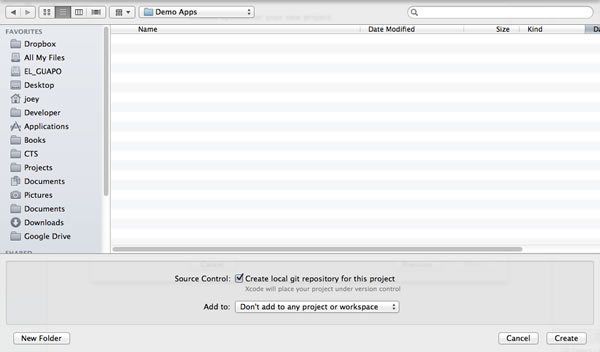

In this step, do this:

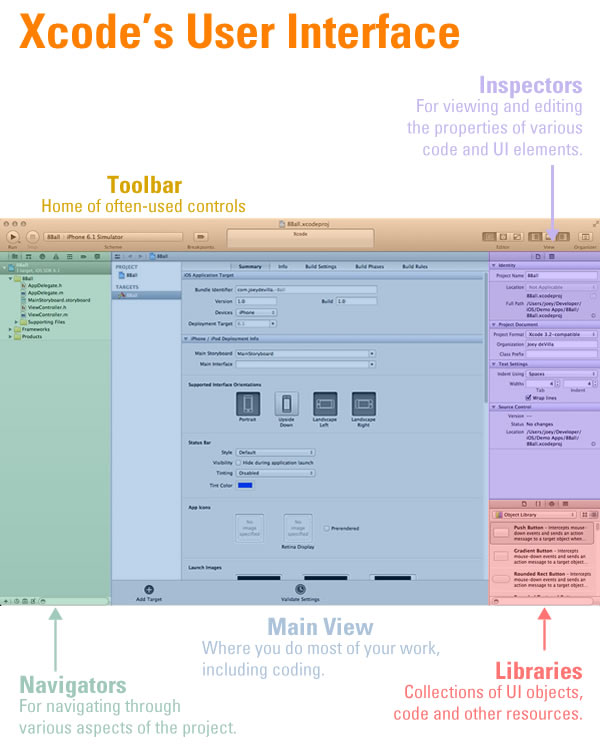

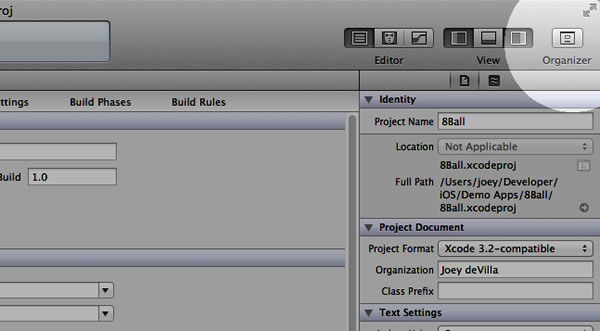

At this point, Xcode has enough information to create a new project. Click the Create button; Xcode will get to work and after a moment or two, you’ll have a project. You’ll be taken to Xcode’s main window, which will look something like this:

Before we get coding, let’s take a quick look at the five major parts of Xcode’s user interface:

If you’ve worked with other IDEs, such as Visual Studio or Eclipse, Xcode’s layout should be familiar to you. Its main window has these five sections:

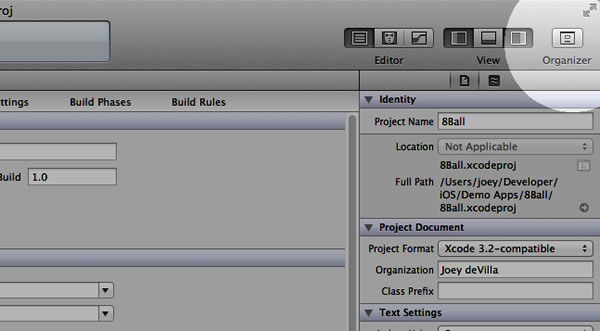

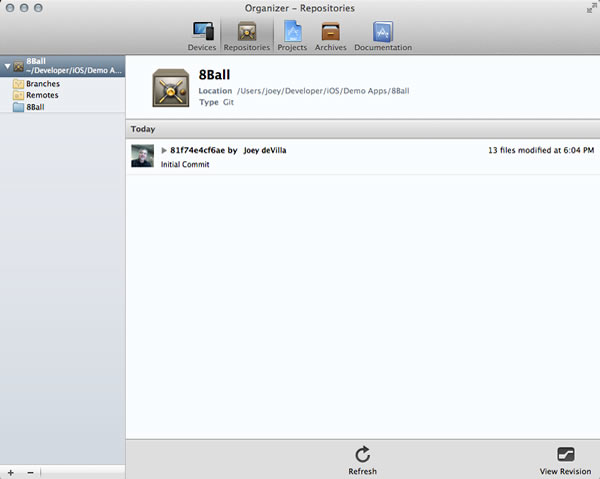

You can look at the local git repository that was created along with the project by opening the Organizer. The button to view it is located near the upper right-hand corner of Xcode’s main window:

Once the Organizer window has opened, click on the Repositories button on its toolbar. You should see a window similar to this one:

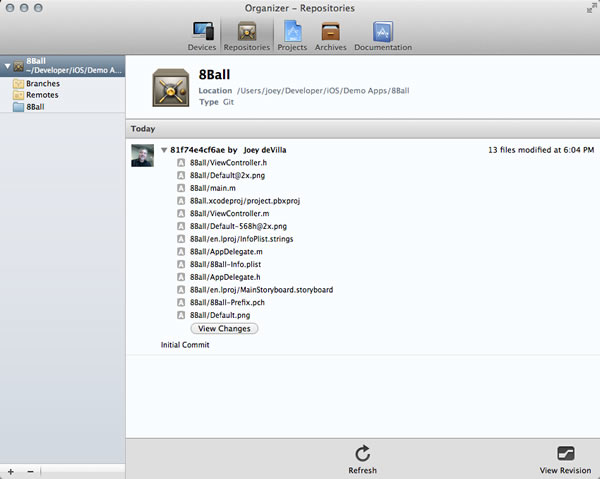

Notice that the first commit has been automatically made for you. If you click on the disclosure triangle for your first commit, you’ll get a list of all the files in your project, each marked with an “A” on the left. That’s “A” as in Git’s file status flag for files that have just been Added:

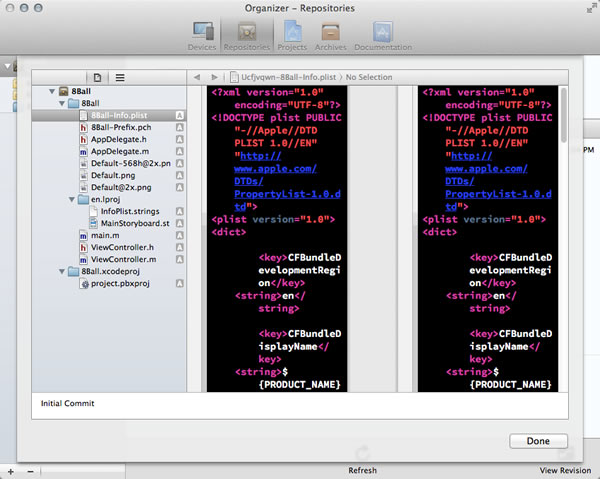

If you click the View Changes button, you’ll be presented with a window that lets you view the diffs for any of the files that were committed:

The “after” pane is the one on the left, and the “before” pane is the one on the right. Since this is our first and only commit so far, the files were newly-added, and thus the “befores” and “afters” are the same.

If you feel like doing a little double-checking on the command, feel free to open a terminal window, go to your project’s directory, and do a git status.

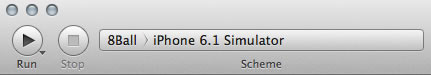

Even though we haven’t put any code into the project yet, it never hurts to take it for a test run. The controls for doing so are by the upper left-hand corner:

Make sure that iPhone 6.1 Simulator is selected in the Scheme menu, then hit the Run button. The simulator will spin up, and you should see something like this:

Now that we’ve got a working new empty project and a local repository, let’s start coding!

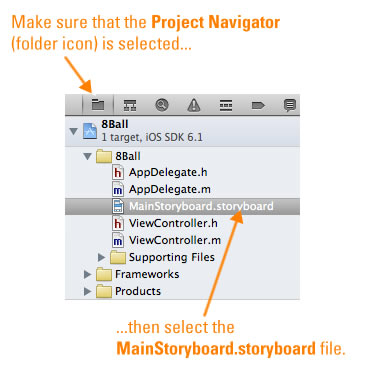

Take a look at the left sidebar, where the navigators live, and make sure the Project Navigator (select it with the leftmost icon, the file folder) is the currently visible one. Select MainStoryboard.storyboard in the Project Navigator:

Xcode should look like this:

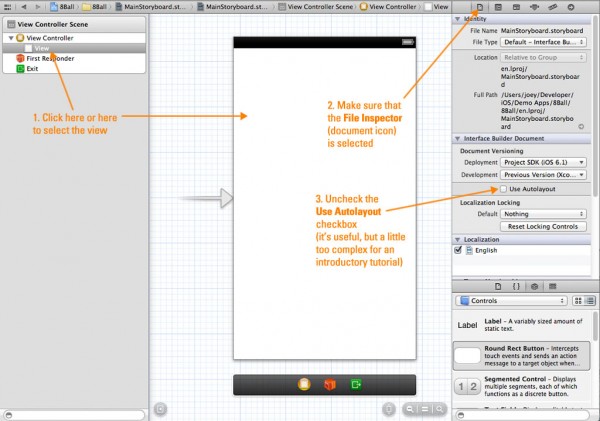

We’re going to do is disable Autolayout for this project. Autolayout is a feature that allows a user interface to adjust itself to various screen orientations (portrait and landscape) as well as screen sizes (which vary among iPhone and iPad models). While it’s useful, it adds a degree of complexity that we don’t want to deal with in these first few tutorials.

To turn off Autolayout, select the view as shown below. Then make sure that the File Inspector (the inspectors are in the upper part of Xcode’s right sidebar; the file inspector is the one with the document icon) is selected, then uncheck the Use Autolayout checkbox:

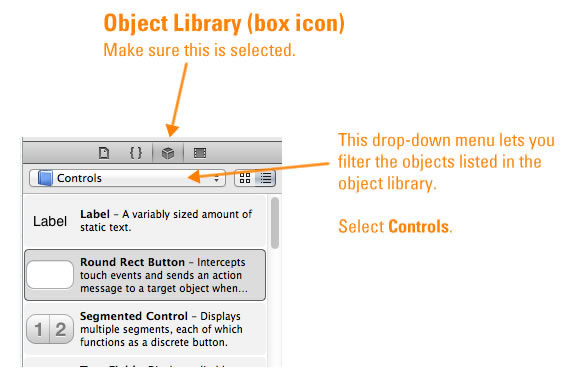

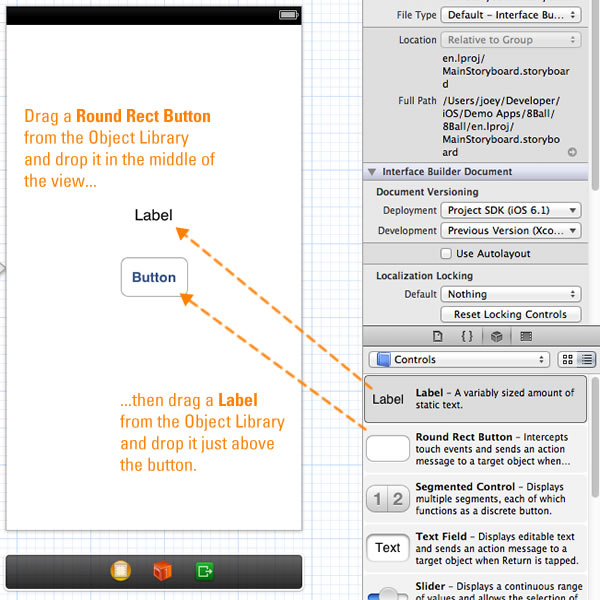

The libraries are also located in the right sidebar, just below the inspectors. We want to put a couple of controls onto the view:

UI controls live in the Object Library (the one with the box icon). Make sure it’s selected, then select Controls from the drop-down menu to filter the list so that only UI controls appear:

Drag a button from the Object Library to the center of the view, then drag a label from the Object Library to a spot just above the button:

Xcode’s user interface drawing tools have guides that “auto-magically” appear to help you lay them out. They’ll help you position controls relative to the position of other controls, and help you center the label and button relative to each other.

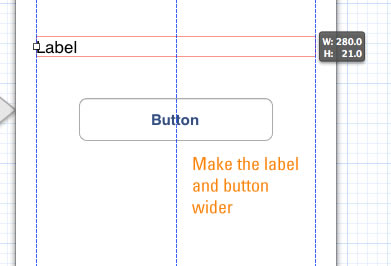

Widen the button the little, and stretch the label so that it’s almost as wide as the entire view. Use the guides to help you determine how wide you should stretch the label:

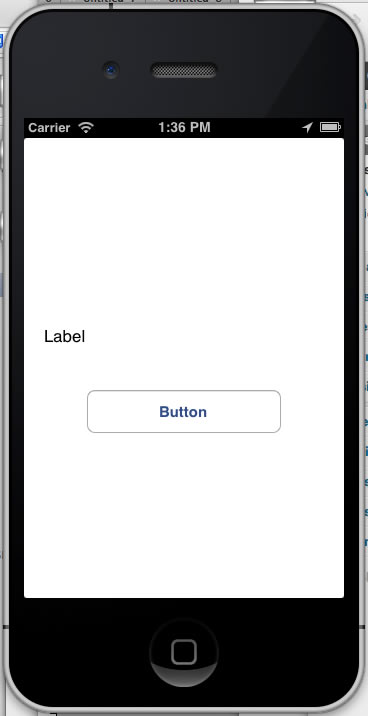

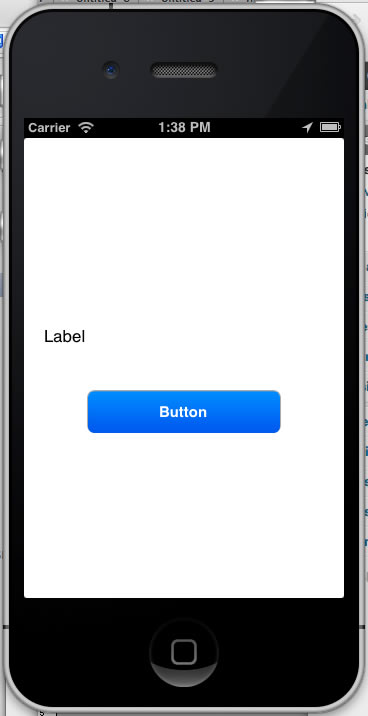

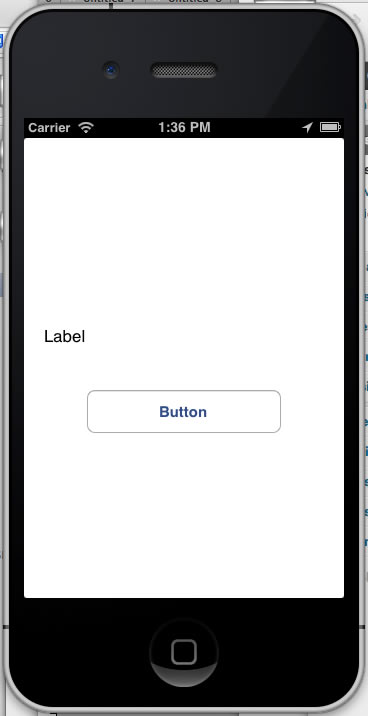

If you run the app now, it’ll look like this:

The button switches to its highlighted state when you press it, and it stays that way as long as your finger’s on it:

It doesn’t do much yet, but it’s a functioning view. The next step is to set up the view controller.

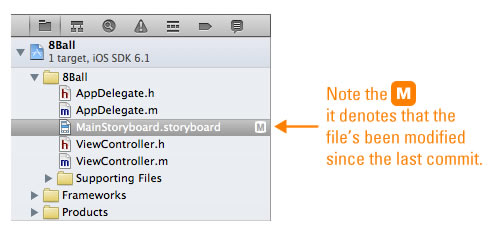

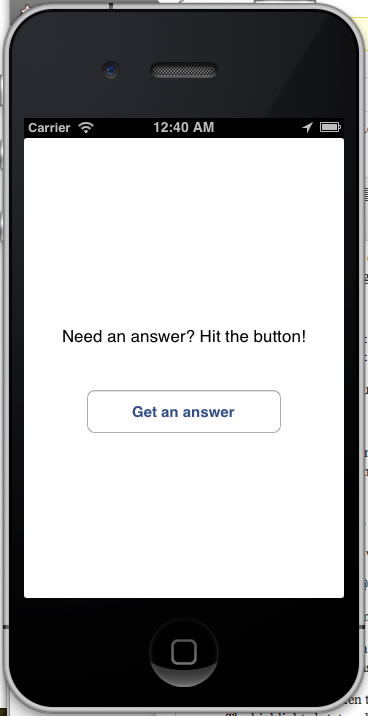

Before we get to the view controller, let’s take a look at the Project Navigator. There’s something new beside the MainStoryboard.storyboard file:

The M is one of Git’s file states, and it denotes that the file’s been modified since the last commit to the local repository. This will happen as you make changes to files in your project’s directory.

Now that we’ve got a view with a label and a button, we want to do the following with them:

Let’s take care of the label first.

Right now, there’s no way for any code you write to refer to the label that you added to the view. You need to create an outlet, which gives you an object that you can use to refer to an control on the storyboard. Once you have an outlet for a control, you can access that control, call its methods and get and set its properties.

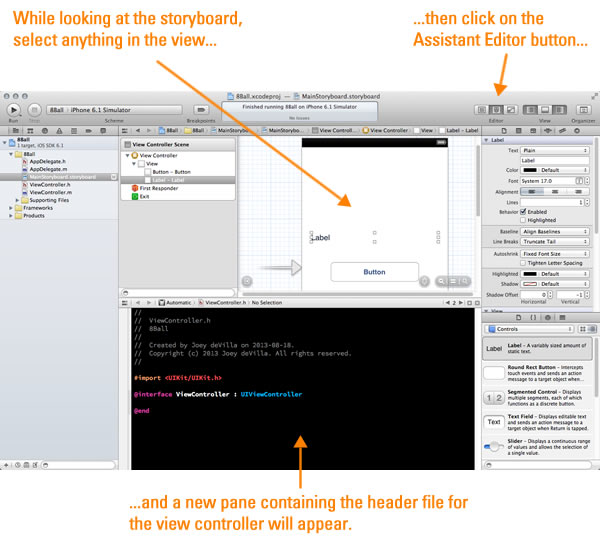

We need to get both the storyboard and the view controller’s header onscreen at the same time. Luckily, the Assistant Editor (its button is pictured below) can help:

The Assistant editor was designed to help with the sort of bouncing about between related files that often happens when working on Objective-C projects. You’ll often find yourself bouncing between a class or module’s .h file (its interface) and its .m file (its implementation), and between a view on the storyboard and its corresponding .h file. The Assistant Editor, when you call it up, considers the last thing you were editing, and opens the related file.

Make sure that the storyboard is in the main view (it should, if you’ve been following this tutorial so far). Click the Assistant Editor button…

…and a text editor for the view controller’s header file will appear. Depending on your Xcode setup, the header file will appear in a pane that will appear either beside or underneath the storyboard.

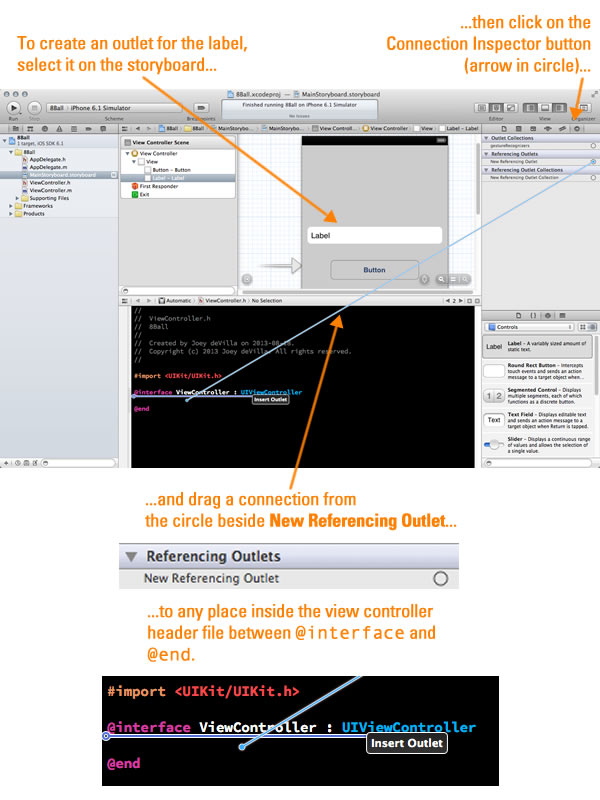

To make the connection, you’ll need to make use of the Connection Inspector, one of the inspectors available in the right sidebar. Make sure that the label is selected in the storyboard, click the Connection Inspector button (the one with the “arrow in circle” icon), and look for an item marked New Referencing Outlet. There’s a circle to its right; drag from that circle to anywhere inside the view controller’s header file that’s between @interface and @end:

When you complete the drag, a little pop-up will appear:

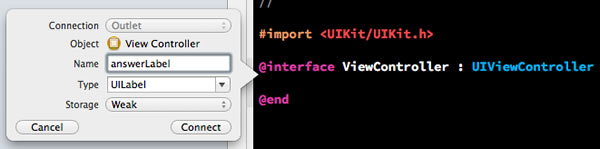

Provide a name for the outlet in the Name text field. I used answerLabel. Click the Connect button. The code in the header file should now be:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h> @interface ViewController : UIViewController @property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *answerLabel; @end

@property?A common practice in many object-oriented languages is to keep a class’ instance variables private and grant access to them via “getters” and “setters” or accessor methods. In Java, following this practice means that you have to do everything yourself: create an instance variable, then define public getter and setter methods that allow outside code to read and write the value in that instance variable.

Objective-C’s @property directive automates this process, telling the compiler to generate the following:

_) character. The ivar’s type will be the same as the property’s. In the case of our answerLabel property, the hidden ivar that will be created is _answerLabel, and its type is UILabel.answerLabel property, the getter’s name is answerLabel, and its type is UILabel.answerLabel property, the setter’s name is answerLabel, and its type is UILabel.If you develop in C#, its properties are similar to Objective-C’s properties. If you develop in Ruby, Objective-C’s properties aren’t too different from using attr_accessor.

Let’s take a closer look at the line that just got added to the view controller’s header:

@property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *answerLabel;

Here’s what each part means:

@property: Indicates that we’re defining a property.(weak, nonatomic): The @property keyword is usually followed by a number of modifiers in parentheses. In this case, the two modifiers are:

weak: This is one of the possible memory management modifiers for properties: in addition to weak, there’s strong, assign, and copy. I’ll cover this in more detail in a later article. For now, you should note that weak is the preferred modifier for outlets.nonatomic: This is one of the possible concurrency modifiers: in addition to nonatomic, there’s atomic. These modifiers specify how properties behave in an environment with threading; by specifying that a property is atomic, you can ensure that the underlying object is locked when its getter or setter is called, thereby preventing threaded code from messing it up. For apps that don’t make use of threading (or if you’ve rolled your own thread-safety mechanism), the general rule is to define your classes’ properties as nonatomic.IBOutlet: A dummy keyword that has no effect on your code. It’s there for the benefit of Xcode’s interface builder (which is why it’s prefixed with IB), so that it knows that this property is an outlet.UILabel *: The type of our property. UILabel is iOS’s class for label controls. If you’re new to C or Objective-C, the * tells you that this property is a pointer to an object of type UILabel.answerLabel: The name of our property.Now that we have an outlet named answerLabel that’s a property of the view controller, we can now refer to the label in code simply by using self.answerLabel.

We also need some way for our code to be notified when the user presses the button. That way is an action — a method that gets called in response to an event. Creating an action is pretty similar to creating an outlet.

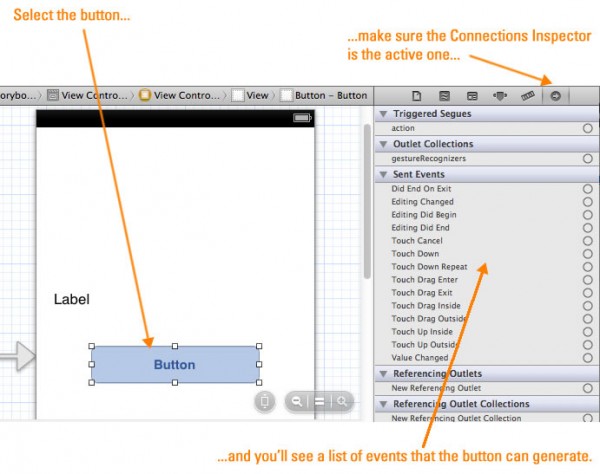

Select the button, then make the Connections Inspector the active one. A list will appear in the right sidebar:

Take a look at the section of the list marked Sent Events. This lists the events that the button can respond to. We’re interested in the Touch Up Inside event, which happens when the user presses on the button, then releases it while his/her finger is still within the bounds of the button. It’s the event that corresponds to a regular button press, so it’s the one we want to respond to.

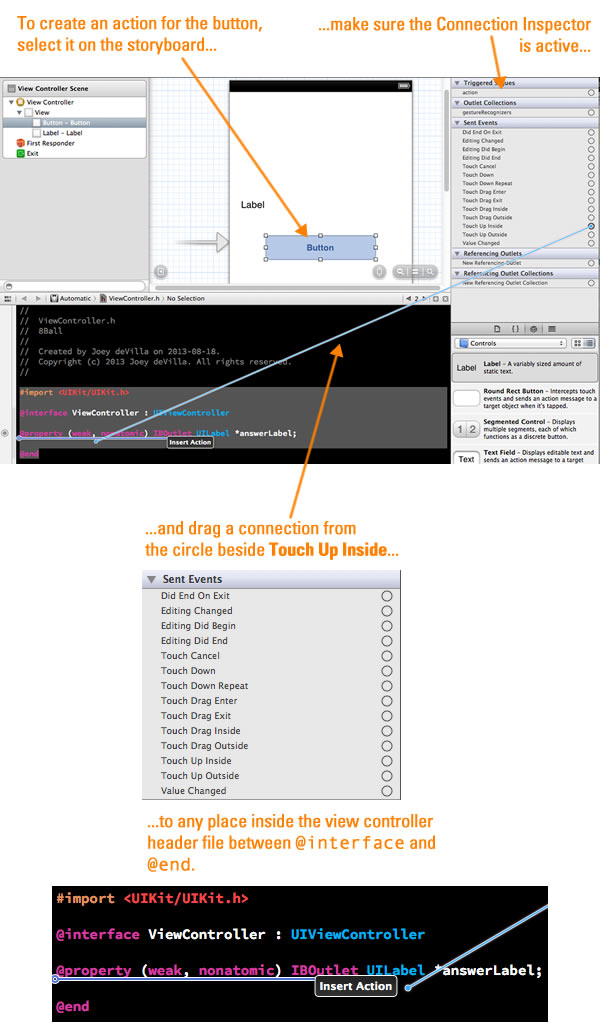

Creating an action is similar to creating an outlet — you create one by selecting an event and connecting it dragging it to the view controller’s hear file. Make sure that the button is selected in the storyboard and that the Connection Inspector is active. Drag from the circle beside Touch Up Inside to anywhere inside the view controller’s header file that’s between @interface and @end:

When you complete the drag, a little pop-up will appear:

When you complete the drag, a little pop-up will appear:

Do the following:

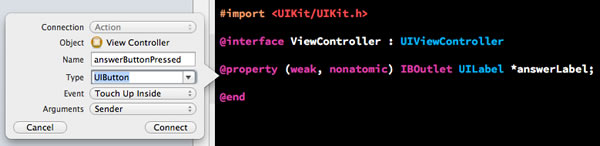

answerButtonPressed.Click the Connect button. The code in the header file should now be:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h> @interface ViewController : UIViewController @property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *answerLabel; - (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender; @end

Let’s take a closer look at the line that just got added to the view controller’s header:

- (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender;

It’s the signature for a method. Here’s what each part means:

-: The - means that this method is an instance method as opposed to a class method.(IBAction): This is the return type of the method. IBAction is #defined to be a synonym for void. It’s there for the benefit of Xcode’s interface builder (which is why it’s prefixed with IB), so that it knows that this property is an action.answerButtonPressed: the name of the method.(UIButton *)sender: sender is the name of the single parameter this method takes, and its type is UIButton *, a pointer to object of type UIButton.Adding the action put the interface for its method in the view controller’s header file, but that’s not the only file that changed. If you look at the view controller’s module or implementation file (ViewController.m), you’ll notice that the implementation for the method was placed there. It’s an empty method and looks like this:

- (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender {

}

We now have an outlet for the label and an action for the button. We can now write some code to respond to button presses by changing the text inside the label. Change the implementation of answerButtonPressed in ViewController.m by adding a line:

- (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender {

self.answerLabel.text = @"You pressed the button!";

}

In this one method, we’re using:

Note the @ in the line:

self.answerLabel.text = @"You pressed the button!";

When you put text in quotes preceded by the @ sign, you’re using Objective-C shorthand for “create an NSString object containing this text. NSString is the string class for work in Objective-C, and it has a whole lot of useful features including Unicode support. Without the @, you’re creating a plain old C string, which isn’t an object type, but a simple zero-terminated C array of ASCII characters.

If you run the app in the simulator now, you’ll see this at the start:

But after you press the button, it’ll look like this:

Let’s make one more change. Right now, when you run the app, the label and button still contain their default text at the beginning. Let’s change their text to something more suitable.

There are two ways to change the initial contents of the label and button. One way is to use Xcode’s interface builder and make the changes in the storyboard. This is as simple as double-clicking on the label or button, which puts them in a mode that lets you edit their text. I find that this is fine for quick-and-dirty projects and hashing out prototypes.

The other way is to set the contents of the label and button in code. Every view has a method named viewDidLoad, which gets called immediately after the view is loaded into memory, but before it’s displayed. It’s an excellent time to run all sorts of initialization code, including doing all sorts of user interface configuration. I think that this is the more maintainable approach, and it’s the approach we’ll use.

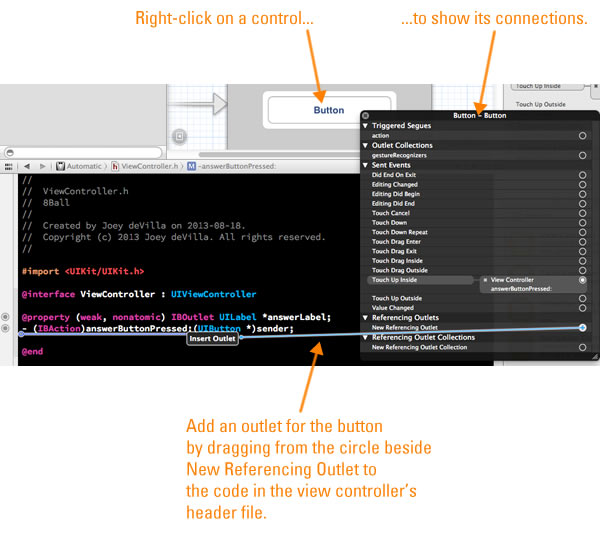

In order to be able to set the button’s content in code, we’ll need to create an outlet for it. This is a good excuse to show you another way to create an outlet. With both the storyboard and the header file for the view controller visible, right-click on the button. A pop-up containing the same items as the Connection Inspector will appear. Drag a connection from New Referencing Outlet to the code in the header, as shown below:

Another pop-up will appear:

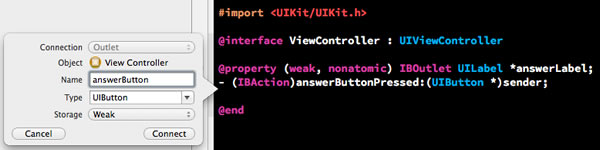

Provide a name for the outlet in the Name text field. I used answerButton. If the Type property isn’t already set that way, change it to UIButton. Click the Connect button. The code in the header file should now be:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h> @interface ViewController : UIViewController @property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *answerLabel; - (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender; @property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UIButton *answerButton; @end

I prefer to put my header files’ @property and IBAction declarations into their own groups, so I’ve rearranged my view controller’s header file to look like this:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h> @interface ViewController : UIViewController @property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UILabel *answerLabel; @property (weak, nonatomic) IBOutlet UIButton *answerButton; - (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender; @end

Now that we have an outlet for the button as well as the label, we can now write some initialization code for both of them. Go to the top of the view controller’s implementation file, ViewController.m. You’ll find the viewDidLoad method’s implementation there. It looks like this:

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

// Do any additional setup after loading the view, typically from a nib.

}

Change viewDidLoad to:

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

// Initialize the UI

// -----------------

self.answerLabel.text = @"Need an answer? Hit the button!";

self.answerLabel.textAlignment = NSTextAlignmentCenter;

[self.answerButton setTitle:@"Get an answer" forState:UIControlStateNormal];

[self.answerButton setTitle:@"Thinking..." forState:UIControlStateHighlighted];

}

Let’s examine these a control at a time:

self.answerLabel.text = @"Need an answer? Hit the button!"; self.answerLabel.textAlignment = NSTextAlignmentCenter;

You’ve probably already figured out what this one does: it sets the initial text of the label to Need an answer? Hit the button!, and then sets the label’s contents to be center-aligned.

Here’s the button code:

[self.answerButton setTitle:@"Get an answer" forState:UIControlStateNormal];

[self.answerButton setTitle:@"Thinking..." forState:UIControlStateHighlighted];

If you’re new to Objective-C, you might find its method-calling syntax odd. Method calls in Objective-C are like this:

[objectName methodName]

In Objective-C parameters become part of the method name. For example, let’s suppose that you were to call a on an object of type Person that set the person’s first and last names. In many popular object-oriented programming languages, the method call to set a Person object’s names to “Tony Stark” would look like this:

somePerson.setName("Tony", "Stark");

In Objective-C, the method call would look like this:

[somePerson setFirstName:@"Tony" lastName:@"Stark"];

…and the proper name for the method would be setFirstName:lastName.

Unlike labels, whose content can be set simply by accessing their text property, you need to call a method to set the text of a button: setTitle:forState:. We use this method twice, once for each of these states:

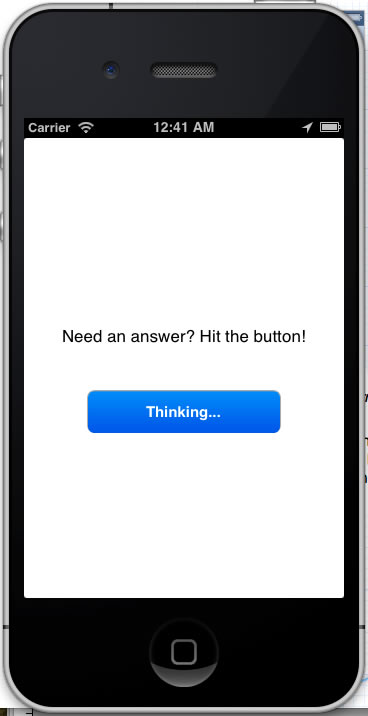

If you the app now, it’ll look like this at startup:

If you press and hold the button, it’ll look like this:

And when you release the button, it’ll look like this:

This looks like a good time commit these changes to the Git repository.

If you look at the Project Navigator (in the left sidebar), you should see this:

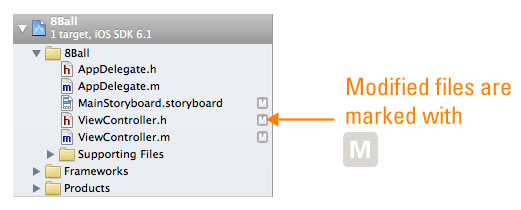

MainStoryboard.storyboard, ViewController.h, and ViewController.m have all been modified, and they’re marked with an M. We want to commit these changes, so fire up the source control by going to the menu bar and choosing File → Source Control → Commit…:

You’ll be taken to a screen where you can review the changes before committing them:

Click on MainStoryboard.storyboard, ViewController.h, and ViewController.m in the sidebar on the left to see the difference between the current versions of these files and the versions from the time they were last committed to the repository. Once you’re satisfied with the changes:

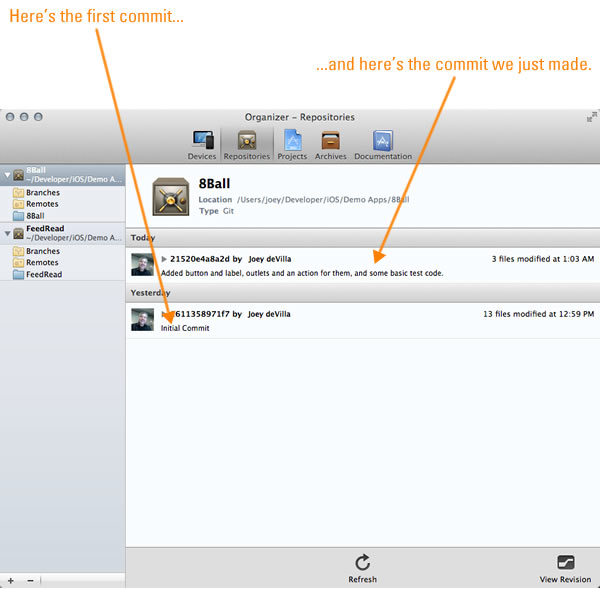

Let’s confirm that the changes were committed. Open the Organizer (once again, you do this by clicking on the Organizer button near the upper right-hand corner of Xcode’s window:

When the Organizer window appears, click the Repositories button. You’ll see the list of commits again, but this time there are two:

All that remains is to write the code to generate random answers for the 8-Ball. This is simple enough to stick into the view controller, but let’s do it the right way and code up a proper model object. We’ll create a model class that will house the random answer generator.

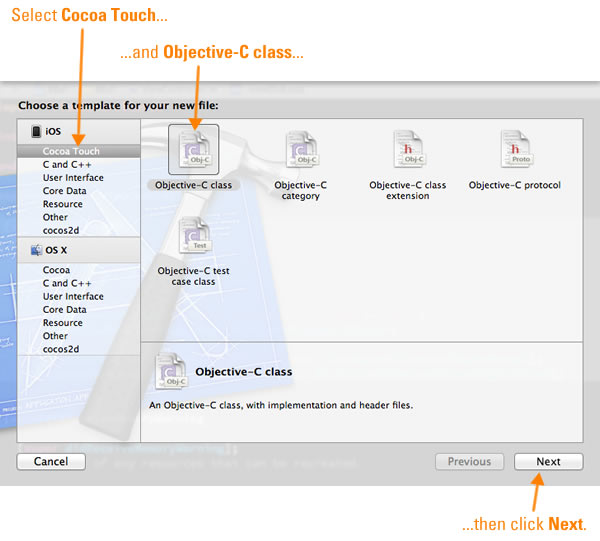

Let’s create a new class. From the menu bar, File → New → File…. You’ll be presented with this dialog box:

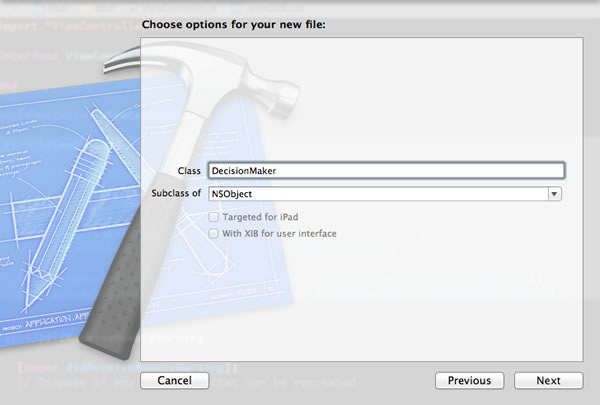

Do as the picture above says. Select Cocoa Touch from the sidebar on the left, then select Objective-C class, then click Next. You’ll then see this:

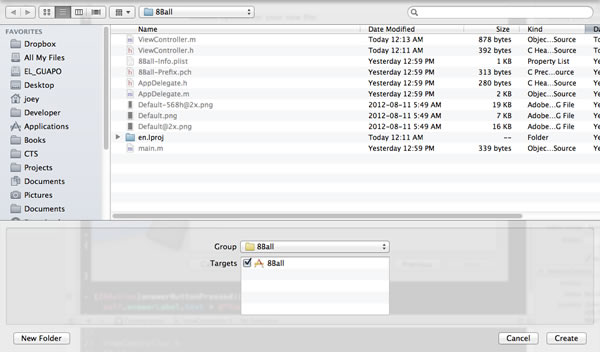

Provide a name for the class — I named it DecisionMaker — and make it a subclass of NSObject, the ultimate base class for every class in Objective-C. Once that’s done, click Next. You’ll see this:

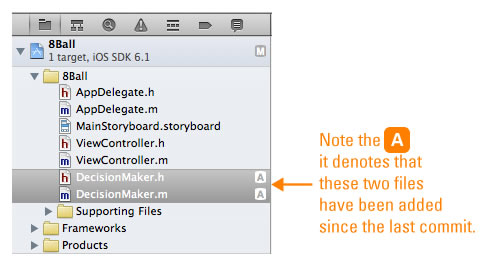

Click Create to save the new class files. You can see them in the Project Navigator, marked with the letter A, denoting files that have been added since the last commit:

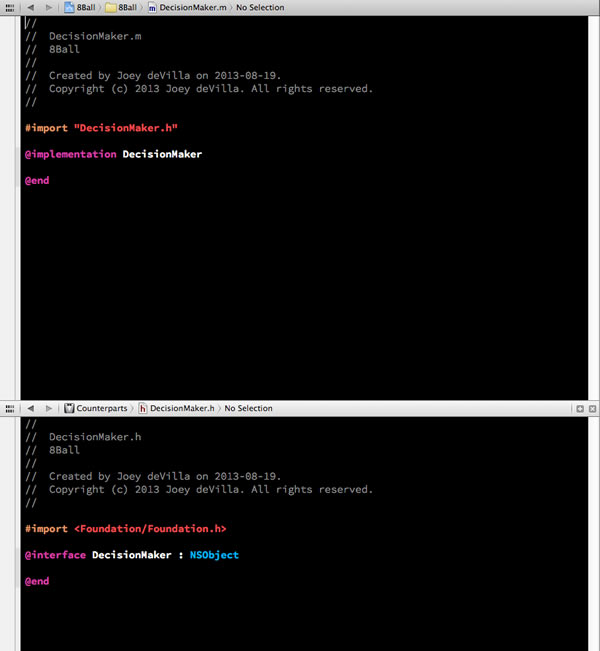

Xcode will automatically open text editors for the header and implementation files for the newly-created class, DecisionMaker.h and DecisionMaker.m:

Time to start coding! First, the let’s write the code for the DecisionMaker class’ header file, DecisionMaker.h:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h> @interface DecisionMaker : NSObject - (NSString *)getRandomAnswer; @end

Right now, DecisionMaker will expose a single method called getRandomAnswer, so we need to put its signature into the header file. getRandomAnswer doesn’t take any arguments, but does return a string.

Now for the implementation:

#import "DecisionMaker.h"

@implementation DecisionMaker {

NSArray *answers;

}

- (id)init

{

self = [super init];

answers = @[

@"Yes.",

@"No.",

@"Sure, why not?",

@"Ummm...maybe not.",

@"I say \"Go for it!\"",

@"I say \"Nuh-uh.\"",

@"Mmmmmaybe.",

@"Better not tell you now.",

@"Why, yes!",

@"The answer is \"NO!\"",

@"Like I\'m going to tell you.",

@"My cat\'s breath smells like cat food."

];

return self;

}

- (NSString *)getRandomAnswer

{

return answers[arc4random() % answers.count];

}

@end

Here’s what you should note from the code above:

@implementation line. This class has a single ivar, answers, which is an NSArray that will hold the answers to randomly choose from. In Objective-C programming, NSArrays are generally favoured over straight-up C arrays.init: This is the constructor, where in addition to constructing instances of the class, the array of answers is initialized.getRandomAnswer, which produces the 8-Ball’s answers.arc4random() is a pseudo-random number generator that’s part of the standard C library and is considered to be the go-to random number generator for general random number needs. It has a decent randomization algorithm and generates pseudorandom numbers between 0 and 2^32 – 1 (which is about 4.3 billion). To get a pseudorandom number between 0 and n, use arc4random() % n.With the model done, it’s time to go back to the view controller’s implementation file, ViewController.m, to make use of it:

#import "ViewController.h"

#import "DecisionMaker.h"

@interface ViewController ()

@end

@implementation ViewController {

DecisionMaker *answerSource;

}

- (void)viewDidLoad

{

[super viewDidLoad];

// Initialize the UI

// -----------------

self.answerLabel.text = @"Need an answer? Hit the button!";

self.answerLabel.textAlignment = NSTextAlignmentCenter;

[self.answerButton setTitle:@"Get an answer" forState:UIControlStateNormal];

[self.answerButton setTitle:@"Thinking..." forState:UIControlStateHighlighted];

// Initialize the decision maker

// -----------------------------

answerSource = [[DecisionMaker alloc] init];

}

- (void)didReceiveMemoryWarning

{

[super didReceiveMemoryWarning];

// Dispose of any resources that can be recreated.

}

- (IBAction)answerButtonPressed:(UIButton *)sender {

self.answerLabel.text = [answerSource getRandomAnswer];

}

@end

Here’s what’s happening in this code:

@implementation line. We’ve added a single ivar, answerSource, which is our model.answerSource in the viewDidLoad method. Since it’s executed just after the view is loaded but before it’s drawn, it’s a good place to do initializing.answerButtonPressed action to set the label’s text to a randomly-selected answer provided by answerSource.Here’s what the app looks like when you run it:

With a functioning model added, it’s a good time to commit the changes. Go to menu bar and choose File → Source Control → Commit… and commit those changes!

Be sure to take a look at the follow-up article, Tweaking the 8-Ball App with a plist, where we make use of property lists, a.k.a. plists, a useful feature. This subtle change to the code makes it easier to maintain.

This is a simple project, and you should feel free to expand upon it or build new projects using this one as a basis. Some other exercises you might want to try include:

DecisionMaker model, but perhaps read from a resource file or even an online file